Page under construction

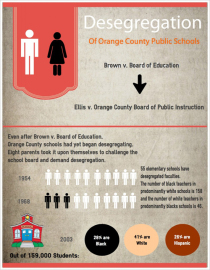

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): End Segregation

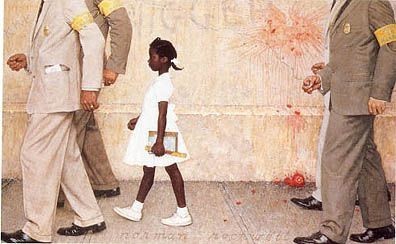

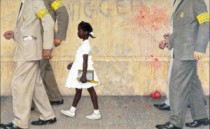

The Problem We All Live With

Wikipedia

The Problem We All Live With is a 1964 painting by Norman Rockwell.

An iconic image of the civil rights movement in the United States,[2] it depicts Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old

African-American girl, on her way into an all-white public school in New Orleans on November 14, 1960 during the process of racial desegregation.

Because of threats and violence against her, she is escorted by four deputy U.S. marshals; the painting is

framed such that the marshals' heads are cropped at the shoulders.[3][4] On the wall behind her is written the racial slur "nigger"

and the letters "KKK"; a smashed tomato thrown at Bridges is also visible. The white crowd is not visible, as the viewer is

looking at the scene from their point of view.[3] The painting is oil on canvas and measures 36 inches high by 58 inches wide.[5] Read more

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): End Segregation

On May 17, 1954 all the Justices of the of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

On May 17, 1954 all the Justices of the of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

Brown v. Board of Education

Wikipedia

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court declared state laws

establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional. The decision

overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896, which allowed state-sponsored segregation, insofar as it

applied to public education. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Warren Court's unanimous (9–0) decision stated that "separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal." As a result, de jure racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. This ruling paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the Civil Rights

Movement.[1] Read more

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse

Frankfurter's Draft Decree in Brown II

Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse

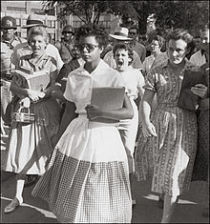

Elizabeth Eckford, age 15, pursued by a mob at Little Rock Central High School on the first day of the school year, September 4, 1957

Elizabeth Eckford, age 15, pursued by a mob at Little Rock Central High School on the first day of the school year, September 4, 1957

Elizabeth Eckford

Wikipedia

Elizabeth Eckford (born October 4, 1941) is one of the Little Rock Nine, a group of African-American students who, in 1957, were the first black students ever to attend classes at Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The integration came as a result of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

Elizabeth's public ordeal was captured by press photographers on the morning of September 4, 1957, after she was prevented from entering the school by the Arkansas National Guard. A dramatic snapshot by Johnny Jenkins (UPI) showed the young girl being followed and threatened by an angry white mob; this and other photos of the day's startling events were circulated around the US and the world by the print press.

The most famous photo of the event was taken by Will Counts of the Arkansas Democrat. His image was the unanimous selection for a 1958 Pulitzer Prize, but since the story had earned the Arkansas Gazette two other Pulitzer Prizes already, the Prize was awarded to another photographer for a pleasant photograph of a two-year-old boy in Washington, D.C. A different photo taken by Counts of Alex Wilson, a black reporter for the Memphis Tri-State Defender being beaten by the angry mob in Little Rock the same day, was chosen as the "News Picture of the Year" for 1957 by the National Press Photographers Association. This image by Counts prompted President Dwight D. Eisenhower to send federal troops to Little Rock. [2] Read more

Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (No. 1.)

Argued: Argued December 9, 1952

Decided: Decided May 17, 1954

Opinion

WARREN, C.J., Opinion of the Court

[p*486] MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion. [n1] [p487]

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, [p488] they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called "separate but equal" doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Fergson, 163 U.S. 537. Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case, the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools. Read more

National Park Service - Brown v. Board of Education

National Park Service

Brown v. Board of Education

The Road to Justice

The story of Brown v. Board of Education, which ended legal segregation in public schools, is one of hope and courage. When the people agreed to be plaintiffs in the case, they never knew they would change history. The people who make up this story were ordinary people. They were teachers, secretaries, welders, ministers and students who simply wanted to be treated equally. Read more

Brown v. Board of Education, 1954: End Segregation

Timeline of the Struggle for Civil Rights at University of Florida

Virgil Hawkins Story Paving the Way for Equal Rights

Desegregation Pioneers to Be

Honored During UF Constitution Day Program

FlaLawOnline University of Florida Levin College of Law

Published: September 15th, 2008

Fifty years ago one man changed the course of history for higher education in the state of Florida. African-American, academically eligible, and eager to start his instruction, Virgil Hawkins was denied admission to the University of Florida College of Law based solely on his race.

With the legal assistance of future Associate Justice of the United States Thurgood Marshall, it took nine years, five Florida Supreme Court and four U.S. Supreme Court rulings before Hawkins broke the color barrier for students at the University of Florida. As a result, more than 12,000 African-Americans have since earned degrees at the University of Florida.

"Virgil Hawkins and the other students of color who followed demonstrated remarkable personal courage and persistence," said Robert Jerry, dean and a Levin, Mabie and Levin professor of law. "Today, UF has a more diverse student body, one that more closely matches the population of Florida and the nation."

Hawkins’ efforts opened the door for others, including George H. Starke Jr. who in 1958 was the first African-American to be admitted to UF’s College of Law; W. George Allen, who in 1962 was the first African-American to graduate with a UF Law degree; and the Hon. Stephan Mickle one of the first African-American students to be admitted to UF for an undergraduate degree.

To commemorate UF’s desegregation and its positive effects on education, the public is invited to attend the 50th Anniversary of desegregation during UF’s Constitution Day Program at the Levin College of Law on Sept. 17, 2008.

The event will take place in the Chesterfield Smith Ceremonial Classroom 180 from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. The commemoration will include George H. Starke Jr. and relatives of the late Mr. Hawkins and prominent alumni of the College of Law, including the Hon. Stephan Mickle, United States District Judge, Northern District of Florida. College faculty will provide an academic perspective on the legal process of desegregation.

Parking restrictions at the college will be lifted for the day.

Fast Facts:

- In fall 2007, 51,725 students were enrolled at the University of Florida, including approximately 4,300 African-Americans, 6,000 Hispanics and 3,800 Asian-Americans.

- 2008 Levin College of Law minority representation: 25.4 percent. This includes Asian, 8.56 percent; African-American, 5.79 percent; Hispanic 10.57 percent; and Native American 0.5 percent.

- 1946-1958 – 85 African-American students apply to the University of Florida and are denied admission.

- 1949 – Virgil Hawkins and William T. Lewis are denied admission to UF College of Law.

- 1954 – Brown v. Board of Education decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. In a companion decision, the court orders the University of Florida is ordered to admit Virgil Hawkins. The state resists the ruling. Virgil Hawkins brings his case before the Florida Supreme Court five times and the U.S. Supreme Court four times.

- 1957 – Florida Supreme Court upholds Virgil Hawkins’ denial of admission. Justice Stephen O’Connell, who later served as UF’s president, concurs in the decision.

- 1958 – Hawkins withdraws his application to the UF College of Law in exchange for the desegregation of UF graduate and professional schools.

- 1958 – George Starke is the first African-American to be admitted to UF’s College of Law.

- 1959 – College of Law celebrates 50th anniversary.

- 1962 – W. George Allen is the first African-American to receive a degree from the UF College of Law.

- 1965 – Stephan Mickle is the first African-American to earn an undergraduate degree from UF, later earning his law degree from UF in 1970.

Desegregation Pioneers to Be Honored Dur[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [76.2 KB]

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of The Integration of the University of Florida (PDF)

The Integration of the University of Florida

UFLaw50thAnnivProgram.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [428.4 KB]

Florida Trend's 'Icon' Series

W. George Allen is a 'Florida Icon'

Attorney, in 1962 became the first African-American graduate of the University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale; age 77

Art Levy | 11/5/2013

» I was born in Sanford, Florida, which used to be a totally segregated community. When I was in college, I was home for a visit and went to the public library to do some research for a project, and I was told that I couldn’t come into the white library. I just walked past the lady and found the books I needed and sat down. They whispered and pointed, but nobody beat me up, so I did my research.

» It was an injustice that the Florida Supreme Court — all those white justices — kept denying Virgil Hawkins the right to go to the University of Florida. Virgil kind of made a deal that he would give up his right to go if they would admit other blacks, so Virgil sacrificed for me.

» I started working in the fields when I was about 10 years old. The white farmers would close down the black schools in the winter because Sanford was a farming area, mostly celery at the time, and all of us blacks who were able-bodied had to work in the fields. People were arrested for not working.

» When I arrived at the University of Florida, they wouldn’t let me live at married student housing because we were black. I would receive telephone calls, saying, ‘nigger, nigger we’re going to kill you,’ and I’d tell them to go hell. My dad gave me a rifle and said, ‘if they come to your house, shoot them.’ I had young kids, so I taught them how to shoot. I made it known that I don’t believe in non-violence like Martin Luther King. You bother me, I’m violent.

» I fish the St. Johns River and Everglades City on the west coast. I like to fish in Martha’s Vineyard, too. My wife and I have a house there. We’ve been going to Martha’s Vineyard longer than Barack Obama.

» A friend of mine, Percy Lee, we were working in the fields cutting celery, along with other youngsters. The overseer, the straw boss, his name was Red Tile. He had a bad attitude and hated black folk. He and Percy got into an argument about how Percy was packing the celery. He said Percy sassed him and that ‘no nigger could talk to a white person this way.’ So, he got a machete knife and he said he was going to kill Percy. Percy’s mother and my mother and father and a lot of the other grown-ups told him, ‘no you won’t.’ They circled Percy, and I was in there with them. We had to get Percy out of the field because the guy was really going to kill him.

» I was admitted to Harvard and the University of California at Berkeley, but I’m a native Floridian, and I felt that somebody had to integrate the University of Florida. The racists told me I didn’t belong there and I’d never graduate. I got into one or two fights with students who were disrespectful, but I never considered quitting. I made it known that you’re not going to run me away. You’re not going to scare me. I’m going to outstudy all of you, and I’m going to graduate.

» In law school, one of the guys asked me if I would be offended if someone used the ‘n’ word and I said yes. It’s offensive. It’s denigrating. The people who try to popularize that word today are wrong.

» The first time I was offered a judgeship, they weren’t making a lot of money back then. Nixon was president. I think they were making $36,000 a year, and frankly I was making more. Also, judges have to be impartial, like referees, and I have an opinion about every damn thing.

» Our educational system in Florida is in shambles. This Jeb Bush crap of rating schools and letting all the students who want to leave their school get vouchers to go to good schools just leaves all the schools in the poor communities as F schools. What we’ve done is we’ve reverted back to segregated schools in poor communities. Jeb Bush screwed up our educational system. It was never about anything but privatizing education and making money for his friends.

» My father instilled in me the attitude that you don’t accept injustice. If you have to fight, fight. He was that way. He didn’t take any crap.

» I was 36 and I saw this yellow Rolls-Royce and the wife allowed me to buy it. I got stopped a lot by cops, so I got rid of that one and bought a gray one. At the time, I was doing a lot of civil rights work, and the IRS audited me for 15 straight years. My accountant, who formerly worked for the IRS, told me in order to stop the audits, get rid of the Rolls-Royce. I said fine. I bought a brand-new Checker, and the audits stopped.

» The Supreme Court of the United States is now killing voting rights. They’re trying to undo all the civil rights gains. The fight continues.

» I did a lot of civil rights work. Discrimination cases. Housing. Education. I helped integrate the public schools in Hendry County and Broward County. The good thing about being a lawyer is you can work in so many different areas. I was also involved in criminal law. I had some great first-degree murder cases. I did drug cases early. Where ever the money was, I tried to get there. That ’s what you have to do when you’re in private practice.

W. George Allen is a 'Florida Icon'.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [467.8 KB]

Remembering "Firsts" on the path to UF integration

By Pedro Malavet, professor of law (PDF)

Constitution Day at the University of Florida, scheduled for Sept. 17, is dedicated to a remembrance of desegregation at UF. As the university enters its 50th year of desegregation, it is appropriate to reflect on the tremendous progress we’ve made towards the ultimate goal of racial integration.

The bitter Civil Rights struggle that first opened the doors of educational opportunity to people of color on this campus seems very far removed from modern experience —

as do the individual struggles of the men and women who put themselves on the line to push those doors wide. Yet, we cannot possibly understand the significance of our current, diverse student body

unless we remember and acknowledge the truly heroic individual struggle

these men and women endured to achieve it.

Admission into the UF College of Law on Sept. 15, 1958 of a single African-American student, George Starke, came nearly a full 100 years into the university’s existence, and mid-point in the College of Law’s history. His matriculation marked the end of extrajudicial and judicial steps to desegregate the University of Florida, but it came at great personal cost to another African-American applicant, Virgil Hawkins.

In 1949, Virgil Hawkins was among six African-American students who applied for admission to several graduate schools at UF, including the College of Law. On the advice of their counsel, they applied for admission to programs that were not offered at the historically black Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College. Their applications were rejected by the University of Florida solely on the basis that they were not white. Hawkins and William T. Lewis were denied admission to the College of Law and — with the assistance of future Justice Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund — they joined three other rejected UF applicants in filing suits to end the racist exclusion rules.

The litigation involving the law school lasted nine years; it produced four opinions by the Supreme Court of the United States. The state of Florida, through Florida Supreme Court rulings and other methods, repeatedly sought to maintain an all-white student body at the University of Florida; the state offered to and indeed created a “separate-but-equal” law school for blacks at FAMU. When federal courts rejected all attempts to enforce segregation and ordered the State of Florida to admit Hawkins to the College of Law, the Florida courts and state executive officials engaged in additional delaying tactics.

Finally, in 1958, Hawkins, who was by then the only remaining lead plaintiff in the case, abandoned his own aspirations to attend the College of Law by agreeing to

drop his suit against the state — ending nine years of litigation — if the state would desegregate university admissions. On Sept. 15, 1958, George H. Starke, Jr. enrolled in the University of

Florida College of Law, becoming the first African-American student to enter the university. In 1962,

W. George Allen became the first African-American to receive a degree from the UF College of Law. In 1965, the Honorable Stephan Mickle, United District Judge in the Northern District of Florida,

became the first African-American to earn an undergraduate degree from the university. Hawkins went on to graduate from New England School of Law in 1964 and

became a member of The Florida Bar in 1977. Read more

By Pedro Malavet, professor of law

UF_Op-ed.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [12.9 KB]

National Forum to Observe 50th Anniversary of Supreme Court School Desegregation Case, UF Law Communications

Desegregation - UF Law Magazine Fall 200[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [354.5 KB]

Virgil Hawkins and the Fight to Integrate the University of Florida Law School - The Florida Memory Blog

Virgil Hawkins the Fight to Integrate the University of Florida Law School

The Florida Memory Blog

Posted on June 25, 2014 by Kathryn

On May 13, 1949, a forty-three year old man from Lake County named Virgil Darnell Hawkins received a letter from the University of Florida Law School rejecting his application because he was African-American.

Hawkins refused to accept the prejudiced decision without a fight, and promptly filed a lawsuit against the Florida Board of Control in 1950. His legal battle would carry on for nine years, laying the foundation for integrating graduate and professional schools in Florida.

Despite the larger civil rights victory, Hawkins emerged from the ordeal partially defeated as he never gained admission to the institution he considered "one of the finest law schools in the country." The case of Virgil Hawkins v. Board of Control brought Florida into the national school desegregation conversation, serving as an antecedent to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Furthermore, Hawkins’ ordeal underscores the tenacity with which segregation advocates fought the drive for an integrated university system, some even going so far as to suggest that such a change would incite "public mischief."

Before Virgil Hawkins took his stand, there was no law school for African-Americans in Florida. Rather than fund a separate institution in Florida or permit African-Americans to attend an existing school with whites, the state instituted a law in 1945 to provide scholarships for select African-American students to study at segregated law schools outside the state. When Virgil Hawkins refused to accept that alternative, the Board of Control approved plans to open a segregated law school at Florida A&M College. By 1950, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled on two related cases, Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma, professing the inherent inequality of segregated graduate institutions. Despite these rulings, the Florida court still refused to admit Hawkins, and would continue to refuse even after the so-called Brown II decree issued by the Supreme Court in 1955 to clarify the original Brown decision. Hawkins persisted in his fight against the state’s segregationist position, but more challenges were on the way. In 1958, the Board of Control established a new minimum score on the law school entry exam for incoming students, setting the admission threshold fifty points above Hawkins’ 1956 score. As a result, Hawkins was officially denied not because of his race, but rather because he was disqualified by the new rules regarding test scores. Later that summer, federal district judge Dozier DeVane mandated that all qualified applicants be admitted to graduate and professional schools in Florida regardless of race.

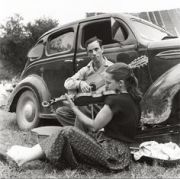

Judge Dozier DeVane, who ruled that qualified applicants had to be admitted to law and graduate programs regardless of race, stands at right in this photo, along with Harrold G. Carswell (center) and an unknown man at left (1953)

Judge Dozier DeVane, who ruled that qualified applicants had to be admitted to law and graduate programs regardless of race, stands at right in this photo, along with Harrold G. Carswell (center) and an unknown man at left (1953)

Nine years after the initial integration suit, African-American veteran George H. Starke, not Virgil Hawkins, enrolled at the University of Florida Law School in September 1958 without incident. As for Virgil Hawkins, he eventually received his law degree in New England, and was admitted to the Florida Bar in 1977. He resigned in 1985 following complaints about his practice.

Virgil Hawkins’ case is an excellent example of how the Civil Rights Movement played out in the courtrooms of Florida as much as it did at lunch counters, public beaches, and city buses. The legal battles fought by Hawkins and others laid the groundwork for an integrated education system for all of Florida. Read more

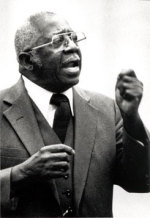

Virgil D. Hawkins speaks with supporters while on recess during his disciplinary case before the Florida Supreme Court (1983).

Virgil D. Hawkins speaks with supporters while on recess during his disciplinary case before the Florida Supreme Court (1983).

Virgil D. Hawkins; Broke Color Barrier To Become Lawyer

The New York Times

AP Obituary

February 15, 1988

LEESBURG, Fla., Feb. 14— Virgil D. Hawkins, who waged a 28-year battle to practice law in Florida and helped break the color barrier at the University of Florida Law School, died Thursday after a long illness. He was 81 years old.

Mr. Hawkins had been in poor health for several months. He died at Munroe Regional Medical Center in Ocala after suffering acute kidney failure, said his wife, Ida.

Mr. Hawkins, who was born in Okahumpka, near Leesburg, taught school and was a principal in Lake County schools in the 1940's after graduating from Bethune-Cookman College.

In 1949, at the age of 41, he applied for admission to the all-white law school at the University of Florida in Gainesville and was rejected because he was black. Mr. Hawkins challenged the state's segregated school system. In 1956, the United States Supreme Court ruled that he should be admitted to the school.

Thwarted by New Barriers

But the Florida Supreme Court invoked the doctrine of states' rights to deny him admission. The state's Board of Control then adopted rigid entrance requirements that made it impossible for Mr. Hawkins to enroll.

In 1976 the Florida Bar urged the Florida Supreme Court to allow Mr. Hawkins to take the state bar examination even though he had attended an unaccredited law school in Massachusetts 20 years earlier. The bar said he should be given special consideration because of his ill treatment while he was trying to enter law school in 1949.

In November 1976, the Florida Supreme Court ruled 7-0 that Mr. Hawkins should be allowed to practice law and waived a requirement that he first take the bar exam.

After a 28-year fight, Mr. Hawkins opened his law practice in a tiny office in Leesburg. But at the age of 77 he found himself before the Florida Supreme Court again because of complaints about his competence and accusations that he had misappropriated $15,000 entrusted to him by a client.

In January 1984, the Florida Supreme Court censured Mr. Hawkins and placed him on probation for two years because of errors he had made in his first cases. Mr. Hawkins, facing two additional complaints, was allowed to resign from the Bar in April 1985.

About Us - Virgil Hawkins Justice Foundation

The Virgil Hawkins Justice Foundation was formed in 2009 to support Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Peggy Quince’s vision to publish the book "Florida’s First Black Lawyers, 1869-1979 to document and honor the achievements, challenges, struggles and prejudices experienced by the first Black lawyers admitted to the Florida bar, including Virgil Hawkins, whose own struggle for access to the profession epitomizes the importance of ensuring equality and justice in access to legal profession. The Virgil Hawkins Justice Foundation, in partnership with the Virgil Hawkins Florida Chapter National Bar Association, organized the Legacy Gala to unveil "Florida’s First Black Lawyers, 1869-1979" and celebrate the avhievements of Florida’s Living Legends. The experiences and biographies documented in "Florida’s First Black Lawyers" made it clear to the members of the The Virgil Hawkins Justice Foundation that there is a continuing need to push for diversity in the practice of law and that obstacles such as bar exam passage should not hinder the pipeline of young talent interested in developing successful legal careers. As such, the Virgil Hawkins Justice Foundation adopted the mission to provide assistance and support to programs for minorities interested in pursuing a legal career; provide support to students through scholarship programs and to develop activities designed to expose minority students to the legal profession. We trust that you will join us in supporting our mission and goal to "Support Access, Justice and Diversity in the Legal Profession". Home page

____________________________________________________

Status of Educational Desegregation in Florida in 1956

The Status of Educational Desegregation in Florida

Gilbert L. Porter, Executive Secretary, Florida State Teachers Association

It should be stated quite candidly at the outset that there has been no desegregation in the public schools of Florida. One might say that we are still in the talking and "planning" stage. Further, there is reason to believe that there will be no spectacular or unusual rush into the waiting arms of integration. It cannot be said, however, that Florida's position has been, or is, one of "wait and see." Some definite and important steps have been taken in the direction of evolving a modus operandi.

Florida's first attempt at circumventing the Supreme Court of the United States came in the form of a legislative bill. The bill, sponsored by Senator Charley E. Johns, former acting governor, instructs county school boards to assign each child to the school "to which he is best suited." Moreover, it makes the determinations of the local boards conclusive of the issue. In addition to its primary purpose, the preservation of segregation, the bill makes possible the use of study groups, special legal counsel to assist local boards, and surveys to channel the local school boards in the rendering of decisions. At first glance, one might think that the bill is simply intended to ease the road of desegregation, but the statements of the sponsor and its supporters negate any such thought. The bill is designed as an out-and-out anti-integration piece of legislation. Some persons who have carefully examined the bill point out, however, that the segregation preservists may have out done them- selves. As Southern School News noted in its issue of July 6, 1955, the loosely worded and multifarious provisions of the bill just might "give local school boards all the legal authority they need to carry out the Supreme Court decision."

Negro parents in four of Florida's sixty-seven counties filed petitions to enter its public schools on a non- segregated basis in September. There was no action taken except referral to study committees. The petitions were not followed by court action. Attorney General Richard W. Ervin seemed to have correctly interpreted the status of things in September when he said: "They [Negroes] apparently realized such radical departure from established social tradition must be approached slowly." In any event, there was no flood of petitions and no rush to sign the four actually submitted.

Read more in The Status of Educational Desegregation in Florida, by Gilbert L. Porter, Executive Secretary, Florida State Teachers Association, The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 25, No. 3, Educational Desegregation, 1956 (Summer, 1956), pp. 246-253

Status of Educational Desegregation in F[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [782.1 KB]

Court's Legacy Intertwined With Martin Luther King Jr.'s

United States Courts

Published on January 15, 2015

It was a turning point for a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr.—and for a young federal judge named Frank Minis Johnson Jr.

In December 1955, as a bus boycott roiled Montgomery, Alabama, King was elected leader of the city’s fledgling protest movement. A month later, Johnson was appointed U.S. district judge in Montgomery’s federal courthouse.

For the next decade, Johnson’s court, the Middle District of Alabama, played a critical role in the civil rights movement, and in two of King’s most defining hours—the Montgomery bus boycott and the 1965 Selma marches.

As the nation celebrates King’s birthday, Johnson’s successors on the bench still take pride in a time when protesters and judges alike braved threats of violence, as they challenged racial segregation.

"It is a critical part of our court’s history," said W. Keith Watkins, chief judge of the Middle District of Alabama, who is leading continuing efforts by the court to pass on lessons from the civil rights era. "In Alabama, race was the issue. It’s difficult to exaggerate how bad it was for blacks."

King and Johnson were newcomers to Montgomery on Dec. 1, 1955, when Rosa Parks was arrested for defying Montgomery’s segregated-bus rules.

In defending the boycott, King invoked the federal courts, which in 1954 struck down school segregation. "If we are wrong, the Supreme Court is wrong," he said. "If we are wrong, the Constitution is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong."

When four riders sued in the Middle District of Alabama, a special three-judge panel, with Johnson and Judge Richard T. Rives in the majority, ruled in Browder v. Gayle that segregated buses violated the 14th Amendment. In December 1956, after the Supreme Court upheld the ruling, the yearlong boycott ended in a historic civil rights victory.

It was the first of numerous landmark cases. Johnson and his colleagues struck down rules denying voting rights to blacks, desegregated Montgomery’s bus depot and airport, and in 1963, ordered Alabama public schools desegregated.

The court’s fairness made it an "oasis" for Alabama blacks, said Judge Myron H. Thompson, who succeeded Johnson in 1980, after Johnson became an appellate judge.

"The federal court in Montgomery, Alabama, was virtually an island. It was the only place where blacks in the state could go and be assured that they were American citizens," Thompson said. "Judge Johnson exemplified the essence of judging. He was an example for all judges, not just me."

In 1965, Johnson and King crossed paths again. The first of three voting-rights marches, from Selma to Alabama’s statehouse in Montgomery, ended in violence on March 7, 1965, when deputies beat protesters as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Asked to halt police harassment, the judge initially prohibited another bridge crossing until both sides could arrange to protect the protesters.

After learning that President Johnson would nationalize Alabama’s National Guard, the judge permitted King and the marchers to cross the Pettus Bridge. His order barred Alabama authorities from "arresting, harassing, thwarting or in any way interfering with the effort to march from Selma to Montgomery."

Johnson received death threats, and the Ku Klux Klan dubbed him "the most hated man in Alabama." A cross was burned on his lawn, and a firebomb damaged his mother’s house. He had constant U.S. Marshal protection for 15 years.

Johnson, who later won the Presidential Medal of Freedom, said his only goal was to enforce the Constitution. "The action of the judges, sitting on the federal bench, hasn’t been for the purpose of effecting social change," he said in a 1974 interview (link is external). "I approach the thing strictly from a legal standpoint. … I have no interest in social change, as a judge." Read more

Pathways to the Bench: U.S. Magistrate Arlander Keys

Law Clerk Rehnquist and Separate-But-Equal Ruling

Did Then-Law Clerk Rehnquist Support Separate-But-Equal

Ruling? Article Cites Summary of Lost Letter

ABA Journal Law News Now

By Debra Cassens Weiss

March 22, 2012

A new law review article considers whether William H. Rehnquist was citing his own views in 1952 when he wrote a memo as a Supreme Court law clerk supporting the 1896

decision upholding the separate-but-equal doctrine.

"I realize it is an unpopular and unhumanitarian position, for which I have been excoriated by ‘liberal’ colleagues," Rehnquist wrote to his boss, Justice Robert H.

Jackson, "but I think Plessy v. Ferguson was right and should be reaffirmed."

During his confirmation hearing, Rehnquist said he had prepared the memo as a statement of Jackson’s tentative views, and they were not his own opinion, the New York Times reports. Now a new law review article (PDF) seeks to debunk Rehnquist’s pre-confirmation claim.

Jackson was part of the unanimous opinion striking down the separate-but-equal doctrine in Brown v. Board of Education, and Rehnquist appeared angry with his boss in the

aftermath, according to the authors of the article, Brad Snyder and John Q. Barrett. The cite Rehnquist’s apparent criticisms of his boss in a 1955 letter written to Justice Felix Frankfurter after

Jackson’s death. Read more

05_snyder_barrett.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [206.5 KB]

Davidson, Gordon B.; Meador, Daniel J.; Pollock, Earl E.; Prettyman, E. Barrett Jr.; and Barrett, John Q. (2012) "Supreme Court Law Clerks' Recollections of Brown v. Board of Education II," St. John's Law Review: Vol. 79: Iss. 4, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol79/iss4/1

http://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1251&context=lawreview

Supreme Court Law Clerks Recollections o[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [3.2 MB]

“The Problem We All Live With,” Norman Rockwell, 1963. Oil on canvas, 36” x 58”. Illustration for “Look,” January 14, 1964. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©NRELC, Niles, IL.

“The Problem We All Live With,” Norman Rockwell, 1963. Oil on canvas, 36” x 58”. Illustration for “Look,” January 14, 1964. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©NRELC, Niles, IL.

Norman Rockwell’s "The Problem We All Live With" To Be Exhibited at The White House

Iconic 1963 Painting on Loan from Permanent Collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

Stockbridge, MA, July 5– Norman Rockwell Museum announces the loan of Norman Rockwell’s iconic painting "The Problem We All Live With," part of its permanent collection, to The White House, where it will be exhibited through October 31. The loan was requested this year by President Barack Obama, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Ruby Bridges’ history-changing walk integrating the William Frantz Public School in New Orleans on November 14, 1960, that later inspired Rockwell’s bold illustration for the January 14, 1964 issue of "Look" magazine. "The Problem We All Live With" was the first painting purchased by Norman Rockwell Museum in 1975. The White House loan was made possible through the support of the Henry Luce Foundation.

"Norman Rockwell Museum is deeply honored that the White House has requested the loan of one of Rockwell’s most important paintings," says Museum Director/CEO Laurie Norton Moffatt. "The painting has come to serve as an important symbol of civil rights, and Museum Trustee Ruby Bridges’ historic journey. We are enormously grateful for the support of the Luce Foundation, that made the loan possible."

Ruby Bridges’ historic walk took place six years after the 1954 United States Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education ruling declared that state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional, and represented a definite victory for the American Civil Rights Movement. Among those Americans to take note of the event was artist Norman Rockwell, a longtime supporter of the goals of equality and tolerance. In his early career, editorial policies governed the placement of minorities in his illustrations (restricting them to service industry positions only), however in 1963 Rockwell confronted the issue of prejudice head-on with one of his most powerful paintings–"The Problem We All Live With." Inspired by the story of Ruby Bridges and school integration, the image featured a young African-American girl being escorted to school amidst signs of protest and fearful ignorance. The painting ushered in a new era in Rockwell’s career, and remains an important national symbol of the struggle for racial equality.

"I was about 18 or 19 years old the first time that I actually saw it," says Ruby Bridges Hall, who now serves on the board of Norman Rockwell Museum. "It confirmed what I had been thinking all along–that this was very important and you did this, and it should be talked about… At that point in time that’s what the country was going through, and here was a man who had been doing lots of work–painting family images–and all of the sudden decided this is what I am going to do… it’s wrong and I’m going to say that it’s wrong."

The illustration appeared in the January 14, 1964 issue of "Look" magazine, and earned Rockwell letters of both praise and criticism from readers unused to such direct social commentary from the illustrator. Rockwell would revisit the theme of civil rights in several other illustrations from the period, and in 1970 received the Million Dollar Club Award from The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), for having contributed $1000 to the organization.

Ms. Bridges Hall, who founded The Ruby Bridges Foundation in 1999 to promote the values of tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences, commends Rockwell for having "enough courage to step up to the plate and say I’m going to make a statement, and he did it in a very powerful way." Learn more about the Ruby Bridges Foundation at www.rubybridges.com.