Lanson v The Florida Bar, Case No. 9:08-80422-Civ

U.S. District Court, Southern District of Florida

Meryl Lanson v. The Florida Bar, Case No. 9:08-80422-Civ, link to court docs

MERYL LANSON, individually,

MARY ALICE GWYNN, individually, (attorney)

And MARY ALICE GWYNN, P.A., (law firm)

A professional association

Meryl M. Lanson, Pro Se, Initial Brief - 11th Circuit Court of Appeals

Fraud on the Court - Karin Huffer.letter to Meryl Lanson July 2008

Court Fight Over Baron's Drags On

TBO.com The Associated Press

Published: August 23, 2008

Updated: May 15, 2013

WEST PALM BEACH -

Fifteen years ago, life was good for Meryl and Norman Lanson. They owned a small and respected chain of men's clothing stores. They had a young son. They had a nice house. They had good friends. They had money.

Then the phone rang.

Baron's grew from a one-store operation in 1946 to 17 stores. It catered to upwardly mobile professional men. The chain had stores from Miami to West Palm Beach, as well as two stores in Orlando and one in St. Petersburg.

Within days of receiving an after-hours call from their banker, they learned a trusted employee and friend - the godfather to their only child - had embezzled $3 million.

Five years later, Baron's, the menswear chain that was a household name in South Florida, was finished.

But while the 52-year-old family business died, the battle was only beginning.

The legal fight, evidence of which fills dozens of boxes stacked in the dining room and garage of their suburban Boca Raton home, has destroyed the Lansons' life.

Meryl Lanson is devoted to proving that the legal system - attorneys, judges and other professionals - conspired against them.

She has fought the battle in state and federal courts. She has sued her former attorneys for malpractice. She has filed complaints with the Florida Bar and the Judicial Qualifications Commission. She has written letters to former Gov. Jeb Bush and Gov. Charlie Crist and copied the missives to the entire Florida Legislature. She has created Web sites, decrying the legal system and what it has done to her family.

And, 15 years into the battle, she shows no sign of stopping.

Last week, she filed yet another federal lawsuit, accusing Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Jeri Beth Cohen of violating her rights to represent herself in a still-unresolved lawsuit that was first filed in 1999. Read more

- Meryl Lanson - onthecommon

TBO.com The Associated Press

Court Fight Over Baron's Drags On _ TBO.[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [73.2 KB]

U.S. District Court, Southern District of Florida

Lanson v. TFB, 08-80422-Civ-ZlochSnow, A[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [1.2 MB]

With notice of voluntary dismissal

PACER docket, Lanson v TFB, w notice dis[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [75.8 KB]

"Goose-stepping Brigades" - Justice Douglas, Lathrop

Justice William O. Douglas, Wikipedia

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898 – January 19, 1980) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he

is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court. In 1975, a Time article called Douglas "the most doctrinaire and committed civil libertarian ever to sit on the court."

Read more

Two years prior to the issuance of the ABA McKay Report, the United States Supreme Court unanimously held in Keller v. State Bar of California, 496 US 1 (1990), adopting in effect the prescient minority Justices' dissents in Lathrop v. Donohue, 367 U.S. 820 (1961), that integrated state bars must not venture into political and ideological waters but stick with the narrow, legitimate functions of integrated state bars. To do otherwise these bars would become, as Justice Douglas pointed out in Lathrop, "goose-stepping brigades" that serve neither the public nor the profession. Read more in the RICO complaint below.

The following text is from a federal lawsuit, Lanson v. The Florida Bar, case no. 9:08-cv-80422-WJZ, United States District Court, Southern District of Florida. The lawsuit was filed April 21, 2008 by attorney Mary Alice Gwynn, who is also a plaintiff in the action.

The lawsuit was not served. The complaint is below in PDF format. Gwynn filed a notice of voluntary dismissal without prejudice July 28, 2008. A copy of the docket and dismissal are below in PDF.

Keller v. State Bar of California, 496 US 1 (1990) link to Justia

Keller v. State Bar of California, 496 US 1 (1990) Wikipedia

Lathrop v. Donohue, 367 U.S. 820 (1961) link to Findlaw

ABA Commission on Evaluation of Disciplinary Enforcement, the "McKay Commission" 1989-1992, link to the ABA

An End to Fraud On The Court

This Blog is intended to keep the public informed as to our efforts to secure Congressional Hearings for "Fraud on the Court."

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

CASE NO.: 9:08-cv-80422-WJZ

MERYL LANSON, individually,

MARY ALICE GWYNN, individually,

And MARY ALICE GWYNN, P.A.,

A professional association,

Plaintiffs,

v.

THE FLORIDA BAR, JOHN HARKNESS,

JOHN BERRY, KEN MARVIN,

RAMON ABADIN, JULIET ROULHAC,

FLORIDA LAWYERS MUTUAL INSURANCE

COMPANY,

Defendants.

_____________________________/

COMPLAINT FOR CAUSES OF ACTION ARISING UNDER FEDERAL RICO AND ANTI-TRUST LAWS, AND CLASS ACTION

COMES NOW the Plaintiffs, MERYL LANSON, MARY ALICE GWYNN and MARY ALICE GWYNN, P.A., and state as follows:

THE PARTIES

Plaintiff, Meryl Lanson (Lanson) is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Palm Beach County, Florida, and more than eighteen years of age. She has filed meritorious Bar complaints with The Florida Bar against lawyers guilty of multiple breaches of The Florida Bar's Rules regarding ethics, which complaints The Bar has improperly refused to process fully.

Plaintiff, Mary Alice Gwynn (Gwynn) is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Palm Beach County, Florida, more than eighteen years of age, and a

Florida lawyer practicing in Palm Beach County, Florida, and a member in continuous good standing with The Bar since she commenced her practice in 1991.

Plaintiff, Mary Alice Gwynn, P.A. is a licensed. professional association doing business in Palm Beach County, Florida since 1993.

Defendant, The Florida Bar, claims to be the state's "official arm" of the Florida Supreme Court, headquartered in Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida,

operating through its Board of fifty-two Governors, designated by the Supreme Court as its "disciplinary" agency.

Defendant, John Harkness (Harkness), is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Florida, the long-time Executive Director of The Florida Bar, and

as such he is the chief executive officer of The Bar, working in Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida. He also serves on the Board of Directors of Defendant Florida Lawyers Mutual Insurance Company (FLMIC).

Defendant, John Berry (Berry), is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Florida, the Legal Division Director of The Florida Bar who reports to

Harkness, and working in Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida. He also helped author the American Bar Association's McKay Commission Report regarding state disciplinary processes, whose key

recommendations The Bar, now under Berry's guidance, is violating.

Defendant, Ken Marvin (Marvin), is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Florida, Director of Lawyer Regulation of The Bar who reports directly

to Berry, and supervises all "discipline" of Florida lawyers.

Defendant, Ramon Ahadin (Ahadin), is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Miami-Dade County, Florida, a member lawyer of The Florida Bar, a Bar

Governor, and a Director on the Board of defendant FLMIC.

Defendant, Juliet Roulhac (Roulhac), is a citizen of the United States, a resident of Miami-Dade County, Florida, a lawyer member of The Florida Bar, a

Bar Governor, and a Director on the Board of defendant FLMIC.

Defendant, FLMIC, is a mutual insurance company incorporated in the State of Florida, headquartered

in Orlando, Florida, and created by The Florida Bar in 1989, purportedly to provide malpractice insurance policies to Florida lawyers.

JURISDICITION

This court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 18 USC 1961 (RICO), 18 USC 1346 (fraud and honest services), 18 USC 1951 (interference with commerce), Title 15 of the United States Code pertaining to restraint of trade and monopolies (anti-trust law), and Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (class action).

VENUE

This court affords the proper venue for this action, given the locations of the various parties, noted above, and in light of the fact that these various causes of action have arisen in the federal courts' Southern District of Florida because of acts in this geographic area.

THE FACTS

The Florida Supreme Court has delegated to The Florida Bar the function of "disciplining" its members in this integrated state bar system. The Supreme Court and The Bar have a fiduciary duty to the public as well as to members of The Bar to exercise that disciplining function through "honest services," afforded all involved in this disciplinary process--both the members of the public allegedly harmed by the unethical practice of law and lawyers who may be targeted for discipline--due process of law, equal protection, and all other constitutionally-guaranteed rights. The Florida Bar unfortunately is being operated, and demonstrably so, in a fashion as to protect itself rather than the public and honest lawyers. It is presently violating federal laws in pursuit of illicit ends, just as the United States Supreme Court predicted would eventually become the case with integrated state bars such as Florida's.

When Miami lawyer Miles McGrane, was President of the Bar in 2003, The Bar commissioned a poll/survey to assess what Bar members thought of the job The Bar was doing with its discipline. A significant number of members surveyed opined that discipline was not being meted out even-handedly based upon what respondent or potential respondent had done, but rather based upon who the respondents were and how well they were connected within The Bar's leadership hierarchy. The Bar was perceived by its own members to be looking the other way if a lawyer enjoyed advantageous relationships with those making or influencing disciplinary decisions.

The following comments from lawyers are related because they indicate not only the concern about a lack of fair treatment and a lack of equal protection in The Bar's

disciplinary process, but also the fact that The Bar was, and has been, fully aware of the problem. This from the Palm Beach Post on March 5, 2004:

Broward County Assistant State Attorney Craig Dyer caned the grievance process "irrational," "knee-jerk" and "heavy-handed"

Gabe Kaimowitz, a Gainesville lawyer and longtime Bar critic, wrote that the association isn’t capable of investigating itself. "If it wants the truth, I'm afraid

the organization can't handle it," Kaimowitz wrote. "My own personal hypothesis is that the system favors the 'white, Christian good-old-boys.' "

Roshani Gunewardene of Altamonte Springs wrote that, if anything, the Bar may be too zealous in pursuing obvious vendettas from losing or opposing parties in

cases. "The grievance system should not be led to harass and humiliate any member of the Bar," Gunewardene's e-mail said.

In 2000, state Rep. Fred Brummer, R-Apopka, proposed a constitutional amendment to take regulation of lawyers away from the Bar and the Florida Supreme Court. The

proposal fizzled, but Brummer feels it got the Bar's attention.

"It's not just the fox guarding the hen house, it’s the fox deciding when the hens can come and go, Brummer said. I think it’s important that the appearance of

cronyism or the good-old-boy network present in the system is removed."

Brummer's favorite example is the ease of a former legislative colleague, Steven Effman. The former Broward County lawmaker and mayor of Sunrise was suspended for

91 days last April after he was accused of having sex with three divorce clients, including one woman who alleged she was billed for their intimate time together.

Brummer said Effman got off easy because he had a close relationship with the Bar and because of his position in the legislature.

Bar President McGrane and The Bar created a Special Commission on Lawyer Regulation ostensibly to suggest improvements to The Bar's disciplinary system. A Jacksonville lawyer and Bar Governor, Hank Coxe, was the chair of this Special Commission, and one of the problems to be addressed was disparate discipline based upon who Bar respondents were rather than what they had allegedly done.

The

Commission issued its report in 2006 as Hank Coxe became President of The Bar, and it failed to address this disparate discipline problem.

More than a decade earlier, in February 1992, the American Bar Association's McKay Commission issued a report entitled Lawyer Regulation for A New Century: Report of the Commission on Evaluation of Disciplinary Enforcement. One of the nine members of the McKay Commission that issued this Report to the ABA was John Berry, a defendant herein, who was at the time overseeing discipline for The Florida Bar.

The McKay Report addresses the chronic shortcomings of disciplinary mechanisms and methods of integrated state bars, and it made twenty-one recommendations for improvements in state bar disciplinary systems. Four of the twenty-one recommendations by the ABA McKay Commission unequivocally state that any involvement of any kind by a Bar and by its officials and Governors in the disciplinary process vitiates the entire process and renders it suspect. Discipline, according to the ABA McKay Commission, must be the sole domain of the judiciary and delegated in no fashion whatsoever to a Bar.

Again, Defendant, John Berry, then of the Florida Bar and now of the Florida Bar, along with eight other individuals, authored the aforementioned McKay Commission Report. John Berry now oversees Defendant, Ken Marvin, who is the Director of Lawyer Regulations and is ultimately in charge of overseeing all disciplinary matters. For example, sitting on every single grievance committee is a Bar Governor acting as a "designated reviewer." This is the most important position in the entire grievance process. This Bar Governor has a direct line of communication to the entire Board of Governors and to Bar officials such as Harkness, Berry, and Marvin. This flies directly in the face of the core recommendation of the ABA McKay Commission that there must be a "Chinese wall" between The Bar's operatives and discipline. It must be solely the domain of the judiciary.

Another of the twenty-one formal recommendations (Recommendation #3) of the ABA's McKay Report is that "lawyer discipline" must protect the public and not lawyers collectively or individually, as is often, correctly, perceived to be the case.

The Florida Bar, despite the ABA's McKay Report, since its issuance in 1992, has continued to violate these core recommendations, so much so that The Florida Bar is now

arguably the most prominent of all state bars in' its flouting of the ABA's McKay Report.

Two years prior to the issuance of the ABA McKay Report, the United States Supreme Court unanimously held in Keller v. State Bar of California, 496 US 1 (1990), adopting in effect the prescient minority Justices' dissents in Lathrop v. Donohue, 367 U.S. 820 (1961), that integrated state bars must not venture into political and ideological waters but stick with the narrow, legitimate functions of integrated state bars. To do otherwise these bars would become, as Justice Douglas pointed out in Lathrop, "goose-stepping brigades" that serve neither the public nor the profession.

The Supreme Court has warned all integrated state bars, then, that those that do not stick with their narrow functions will be treated as if they were "guilds," and they would suffer the same historical fate of guilds-abolition. Guilds have gone the way of the dodo because they were correctly identified as restricting trade, harming the public, protecting professional wrongdoers from accountability, and denying certain professionals the right to earn a living unimpeded by interference from the guild.

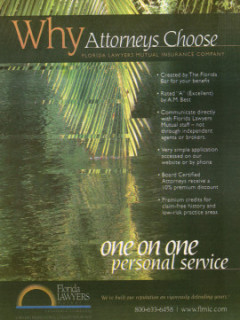

In 1989, The Bar created the Florida Lawyers Mutual Insurance Company, herein called FLMIC, to provide, purportedly, malpractice insurance to Florida lawyers. Indeed, if one goes to the current Internet web site for FLMIC, one finds a remarkable "Welcome" from defendant Harkness explaining the long-standing relationship between The Bar and FLMIC. Harkness does this despite the fact that the FLMIC is supposed to be a private corporation with no ties to The Bar. The FLMIC web site found at http://www.flmic.com makes it clear to anyone viewing it that there is a cozy, ongoing relationship between it and The Bar. The site even links to certain Florida Bar sites.

Indeed, at a recent mediation presided over by former Miami-Dade Chief Judge Gerald Wetherington, a claims adjustor for FLMlC was greeted by the Judge with the words, "I know you. You're from The Bar."

Serving on FLMIC's Board of Directors is not only Harkness, but also Defendant Abadin and Defendant Roulhac, both Bar Governors. Serving also on the FLMIC Board is Alan

Bookman, Bar President immediately before the tenure of the aforementioned Hank Coxe.

Harkness, Abadin, and Roulhac have a fiduciary duty to The Bar, to its members, and to the public in the discharge of their "Bar" duties, particularly regarding

"discipline." Yet, they also have a fiduciary duty to FLMIC and its mutual policyholders. These two sets of fiduciary duties

are in clear conflict with one another, not only conceptually but in fact.

Florida Bar members who are FLMIC policy holders are shielded from discipline by The Bar. By buying FLMIC policies they purchase, in effect, discipline protection, avoiding it altogether or securing more lenient discipline.

One Bar respondent stated, "I was told by The Bar that if I purchased FLMIC insurance my 'disciplinary problems would go away.'"

Plaintiffs are aware of specific instances in which certain Florida lawyers, clearly guilty of egregious ethics breaches in violation of Florida Bar Rules, have been

protected by The Bar from discipline because of their holding FLMIC policies. The result of this protection of FLMIC policyholders is to deny members of the public, who have formally complained to

The Bar, a disciplinary remedy.

Further, lawyers who have no malpractice insurance or who have malpractice insurance coverage with other carriers, do not enjoy this "discipline protection" from 'The

Bar, and they are more likely to be disciplined and disciplined more severely. Thus, the Defendants are ensnared in a commercial relationship with an insurer that is bearing rotten fruit in a

regulatory setting. The guilty are being exonerated and the innocent are being unfairly targeted.

The twentieth century saw the rise of a deadly ideology known as "fascism," one aspect of which was the melding of the state with commercial interests, which is the facet of fascism known as "corporatism" See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corporatism. What the Defendants have done is fall into this fascist trap by blurring the lines between government and commerce in such a way as to increase the power of both, and at the expense of individual liberties.

The illicit reason for the wedding of this governmental state function-the disciplining of lawyers-to what is supposed to be a solely private sector commercial

activity-the sale and purchase of malpractice insurance-is that blocking the discipline of a lawyer, who is an FLMIC policyholder, serves to help insulate him/her from a malpractice action. A member

of the public, told by The Bar that it will not discipline a lawyer guilty of ethics breaches, serves as a powerful disincentive to that complaining citizen to take the next step and bring a

malpractice action. If The Bar itself will not proceed, with all of its resources, why should a single citizen do so, the victim reasons. Further, FLMIC and its Directors, including the three

defendant Bar Governors Harkness, Abadin, and Roulhac, use their influence to prevent adverse ethics findings by The Bar, and thus such would-be findings be used as collateral proof of malpractice

against that lawyer in any civil litigation.

Thus fiduciaries, who have a duty to pursue discipline fairly and equitably, with no respect whatsoever as to who the respondent is, have a powerful commercial

disincentive to do so. What they do have is a fiduciary duty to protect FLMIC and its policyholders. The aphorism that a "man cannot serve two masters" undergirds the very concept, in our system

of law, as to what a fiduciary is. All of the Defendants have breached this duty to serve only one master by virtue of their improper relationship between FLMIC and The Bar. No lawyer or any

other person who understands "conflict of interest" could possibly think that Bar operatives should be sitting on the Board of FLMIC.

Often conspiracies are proven and then unravel, because documents called "smoking guns" are discovered and disgorged from hidden sources, that has now become evident in this scandal pertaining to The Bar's and FLMIC's racket. Plaintiffs have a smoking gun that has appeared in the light of day by the hand of the Defendants themselves. Attached hereto as Exhibit A, and made a part hereof, is a large color advertisement that has been regularly and recently gracing the pages of The Bar's own in-house publication, The Florida Bar News. It is an ad for Defendant, FLMIC. Its message proves the Plaintiffs' case is noteworthy and harmful to the Plaintiffs and the public at large, for the following reasons patent in the ad itself, to-wit:

The advertisement shares with all Florida Bar members its slogan, at the lower left hand corner of the ad: "We've built our reputation on vigorously defending yours." The

related bullet point down the right-hand side reads "Aggressive defense of your reputation." FLMIC is thus using The Florida Bar's publication to send the message that it can be counted upon to

"vigorously" mount an "aggressive defense" of any claim brought by any client who asserts that he has been harmed by the malpractice of a lawyer. By contrast, other state bars are increasingly moving

toward mandatory lawyer malpractice insurance as a measure to protect the public by compensating them by these means. Oregon has mandatory lawyer malpractice insurance - not to protect Oregon lawyers

and their "reputations", but rather to compensate victims of it.

This message and this mindset - FLMIC will do what is necessary to defeat a client's claim - is bad enough. But here is the proof of the insurance and discipline racket

in which all the Defendants are involved. The FLMIC ad proclaims in its last bullet point as to why Florida Bar members should purchase their liability coverage product rather than that provided by

dozens of other insurers:

• Defense for disciplinary proceedings

FLMIC is thus making one of the services it provides under the policy full defense for any lawyer charged with a disciplinary breach by a client. This is significant in at least two regards: 1) it is an acknowledgment of the linkage between malpractice and discipline and the keen interest of FLMIC in defeating any grievance brought because of its impact upon any finding of liability for malpractice, and 2) it is a promise that. FLMIC, which the first bullet point notes was "Created by The Florida Bar for your benefit", will do what it can to defeat any grievance brought by the public to The Bar’s attention! Why in the world should a company created by The Bar be involved in thwarting what is supposed to be The Bar's regulatory function intended to protect the public?

This remarkable ad, then, proves the Plaintiffs' point: FLMIC has been created by The Florida Bar to defeat grievances brought by the public. It could not be clearer. It

says precisely this on the pages of The Florida Bar News. Any lawyer not understanding this message--that to buy this Bar-created insurance product buys one "discipline protection" has missed the

unmissable.

Plaintiff, Gwynn, has been wrongly singled out for "discipline" by The Bar, with the collaborative efforts of all of the Defendants, in large part because she is not an

FLMIC policyholder. Subsequently, Gwynn and Gwynn, P.A. have suffered damages. Plaintiff, Lanson, a Bar complainant, has been denied "honest services" in the processing of her formal Bar complaints

by a conspiracy of all of the Defendants in that certain Florida lawyers who acted in their professional capacities unethically were protected from discipline by The Bar by virtue of the fact that

they were FLMIC insureds.

More specifically, Plaintiff, Meryl Lanson, beginning in 1998 filed bar complaints against Florida attorneys for a litany of egregious ethical violations, including but not limited to, perjury and fraud. The Bar thwarted the disciplinary process by labeling the grievance a "fee dispute." It was not.

The complained of ethics violations, according to The Bar's own Rules, were very serious and, according to Bar guidelines, were deserving of severe punishment.

Nevertheless, the complaint never made it past a perfunctory intake process.

Here is a listing of the ethics breaches by Lanson's attorneys, which The Bar refused even to investigate:

Rule 4-1.1 Competence

Rule 4-1.3 Diligence

Rule 4-1.4 Communication

Rule 4-1.5 Fees for Legal Services

Rule 4-1.7 Conflict of Interest; General Rule

Duty to Avoid Limitation on Independent Professional Judgment.

Explanation to Clients

Loyalty to a Client - Loyalty to a Client is also impaired when a lawyer cannot consider, recommend, or carry out an appropriate course of action for the client because

of the lawyer's other responsibilities or interests. The conflict in effect forecloses alternatives that would otherwise be available to the client.

Lawyer's Interests - The lawyers own interests should not be permitted to have adverse effect on representation of a client

Conflicts in Litigation - Subdivision (a) prohibits representation of opposing parties in litigation. Simultaneous representation of parties whose interests in litigation

may conflict, such as co-Plaintiffs or co-Defendants, is governed by subdivisions (b) and (c). An impermissible conflict may exist by reason of substantial discrepancy in the parties' testimony,

incompatibility in positions in relation to an opposing party, or the fact that there are substantially different possibilities of settlement of the claims or liabilities in question.

Rule 4-1.8 Conflict of Interest: Prohibited and other Transactions. Settlement of Claims for Multiple

Clients.

Rule 4-1.16 Declining or Terminating Representation.

In 1999, when the plaintiff and her husband, Norman Lanson, filed their malpractice action against these attorneys they learned that the attorneys were insured by FLMIC and that one of the attorneys was a defense attorney employed by FLMIC. It became obvious as to why The Bar's judgment and its failure to discharge its fiduciary duty as to discipline, was compromised by its commercial relationship with FLMIC. There is a clear disincentive for The Bar to punish attorneys insured by the Bar's created carrier, as such punishment could be additional support and collateral proof for a claim arising out of legal malpractice. The paper trail of communications between Lanson, The Florida Bar, its Board of Governors, The Supreme Court of Florida, and Florida Lawyers Mutual Insurance Company outlines the devastating affect this improper relationship among The Bar, FLMIC, and the other Defendants has on the unsuspecting public. Lanson has discovered evidence that theirs was not an isolated incident, but in fact, there is a class of individuals similarly harmed.

Plaintiff, Mary Alice Gwynn, is another victim of the illicit relationship among the Defendants, although the harm emanating therefrom has taken a different, albeit

related form. In 2004, Bar complaints were filed against Gwynn by a Florida attorney who enjoyed a relationship with The Bar's outside investigator assigned to the case. This attorney had threatened

Gwynn with a Bar complaint, and then filed it. The lawyer complainant's threat to file a Bar complaint was, of course, an act in violation of Florida Bar Rule 4-3.4(h), as he made that threat solely

to gain advantage in a civil proceeding.

The Bar complaint resulted in a finding of "probable cause" against Gwynn because of a) the relationship between the complainant and The Bar prosecutor, b) Gwynn's status

of not being an FLMIC policyholder, and c) The Bar's becoming aware of her relationship with the plaintiff herein, Lanson.

More recently, the same lawyer complainant has written Gwynn and told her that if she seeks certain relief in litigation in which he and Gwynn are involved, he will file

a new Bar complaint. Such a threat, of course, is a criminal act - extortion - by this Bar complainant. Despite this use of a

criminal threat, The Bar has decided to proceed nevertheless against the victim of it, Ms. Gwynn.

Plaintiff, Mary Alice Gwynn, P.A. has suffered financial losses as a result of the Defendants' actions against Gwynn.

COUNT I: RACKETEERING

Plaintiffs adopt and incorporate the foregoing facts into this count.

18 USC 1961, et sequitur, affords certain civil remedies to persons harmed

by racketeering activities. The Plaintiffs seek all forms of relief afforded them under the Federal "RICO Act."

The multiple "predicate acts" of racketeering engaged in by Defendants include, but are not necessarily limited to: bribery, extortion, mail fraud, obstruction of justice, interference with

commerce, fraud, including but not limited to violations of 18 USC 1951, as well as deprivation by fraud of honest services, as set forth in 18 USC 1346.

More specifically, both The Bar and FLMIC are engaged, one with the other and in conspiracy with the individuals who are Defendants herein, in a pattern of racketeering

activity whereby lawyers are prosecuted by The Bar for "disciplinary" reasons if they are not FLMIC insured. The offering and purchase of an FLMIC malpractice insurance policy constitutes extortion.

FLMIC directors' fees are paid by FLMIC to Defendants Harkness, Rabadin, and Roulhac, who have control, along with other Bar operatives, over The Bar's disciplinary machinery, in order to assure that discipline is not meted out by The Bar against Florida lawyers who are FLMIC insured.

In thwarting proper discipline of FLMIC insured, there is an obstruction of justice,

within the clear meaning of the RICO statute, by all of the Defendants.

Further, all of the Defendants have conspired to interfere with commerce, as a distinct commercial advantage by FLMIC over other legal malpractice carriers, by this racketeering activity that

benefits FLMIC and its insured, at the expense of the public and of unfairly targeted Florida lawyers.

The use by all Defendants of the United States Postal Service, as well as by other means of communication, in furtherance of this pattern of racketeering activity constitutes mail fraud. More generally, the Defendants have engaged in fraud by presenting themselves as if they were fiduciaries providing services and products; when in fact, they have been collaborating and conspiring to enrich themselves and their racketeering enterprises. See 18 USC 1951.

Finally, but perhaps not exhaustively, the Defendants have deprived both the public and non-FLMIC insured "honest services," in violation of 18 USC 1346 by pretending to exercise legitimate regulatory functions, under color of state law, when in fact they have been

actively harming the public by protecting wrongdoers and punishing innocent lawyers, all for commercial gain.

WHEREFORE, Plaintiffs seek all appropriate relief available to them against all Defendants, such relief being set forth in 18 USC 1961, et sequitur, for all of the aforementioned racketeering activities set forth.

COUNT II. ANTI-TRUST

Plaintiffs adopt and incorporate the foregoing facts into this count.

Section 15 of Chapter One of Title 15 of the United States Code affords

individuals harmed by violations of federal anti-trust laws certain remedies which the Plaintiffs herein seek against

the Defendants herein.

The Defendants have all conspired to restrict trade or commerce in pursuit of a monopoly in violation of Section 1, Chapter One, Title 15, United States Code.

More specifically, the Defendants, in establishing FLMIC and in operating it in such a fashion as to improperly wed a governmental function under color of state law, to their commercial interests, have sought and secured a competitive advantage over other legal malpractice insurers in the state by virtue of providing "discipline protection" to their insured, which these other

insurers cannot and would not provide.

Further, the Defendants, have restrained trade with and through FLMIC to deny lawyers their right to earn a living as lawyers in the legal profession, on an equal footing with other lawyers in the state.

The effect of this conspiracy, in this regard, is to harm not only other insurers and certain lawyers, but also to deprive the legal services-consuming public of the

representation of such lawyers whom they would otherwise hire.

All of the Plaintiffs, then, by virtue of being either lawyers or clients have been harmed by the Defendants' restraint of trade and monopolistic practices involving

FLMIC.

WHEREFORE, all Plaintiffs seek, to the extent allowable under Section 15,

Chapter One, Title 15 all damages and all other relief allowable thereunder.

CERTIFICATION OF CLASS

Under Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the three named Plaintiffs herein are typical representatives of a class of individuals yet unknown, who are either members of the public, such as Lanson, who have been harmed by lawyers by means of breaches of The Florida Bar's Rules of Professional Responsibility and whom the Defendants have conspired to protect, at the expense of the public, or who are, like Gwynn, lawyers who have done no wrong and yet who have been targeted improperly for discipline because of the insinuation of commercial concerns and other improper influences upon the disciplinary process.

Other members of this class, then, would include non-lawyers as well as lawyers who have been victimized by the Defendants who are masquerading as public servants, when

in fact they have been tyrants acting under color and under cover of state law.

WHEREFORE, the Plaintiffs seek certification by the court that this action should be and is a class action.

DEMAND FOR TRIAL BY JURY

Plaintiffs demand a trial by jury of all issues so triable.