Page under construction

Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971

Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971

Wikipedia

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA, Pub.L. 92–225, 86 Stat. 3, enacted February 7, 1972, 2 U.S.C. § 431 et seq.) is the primary United States federal law regulating political campaign spending and fundraising. The law originally focused on increased disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns. The S. 382 legislation was passed by the 92nd U.S. Congressional session and signed by the 37th President of the United States Richard Nixon on February 7, 1972.[1]

In 1974, the Act was amended to place legal limits on the campaign contributions and expenditures. The 1974 amendments also created the Federal Election Commission (FEC).

The Act was amended again in 1976, in response to the provisions ruled unconstitutional by Buckley v. Valeo, including the structure of the FEC and the limits on campaign expenditures, and again in 1979 to allow parties to spend unlimited amounts of hard money on activities like increasing voter turnout and registration. In 1979, the FEC ruled that political parties could spend unregulated or "soft" money for non-federal administrative and party building activities. Later, this money was used for candidate-related issue ads, which led to a substantial increase in soft money contributions and expenditures in elections. This in turn led to passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2003 ("BCRA"), banning soft money expenditure by parties. Some of the legal limits on giving of "hard money" were also changed by BCRA.

In addition to limiting the size of contributions to candidates and political parties, FECA also requires campaigns and political committees to report the names, addresses, and occupations of donors of more than $200.

The FECA contains an express preemption clause. The FECA expressly preempts state and federal law with respect to federal elections. Read more

..................Federal Election Commission - FEC...................

The six Commissioners, no more than three of whom may represent the same political party, are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The Commissioners serve full time and are responsible for administering and enforcing the Federal Election Campaign Act. They meet in closed sessions to discuss matters that, by law, must remain confidential, and in public to formulate policy and vote on significant legal and administrative matters. Read more

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION

999 E Street, NW

Washington, DC 20463

- Federal Election Commission YouTube Channel

Federal Election Campaign Laws

First Printing, March 2015

United States Code (links to LII)

TITLE 52. VOTING AND ELECTIONS

Subtitle III—Federal Campaign Finance

Chapter 301—Federal Election Campaigns

Subchapter 1—Disclosure of Federal Campaign Funds

Title 52. Voting and Elections

Title 26. Internal Revenue Code

Title 2. The Congress, Chapter 65

Title 18. Crimes and Criminal Procedure

Title 28. Judiciary and Judicial Procedure

Title 36. Patriotic and National Observances, Ceremonies and

Organizations

Title 47. Telegraphs, Telephones and Radiotelegraphs

Federal Election Campaign Laws, March 20[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [1.5 MB]

Title 11 of the Code of Federal Regulations

Wikipedia

CFR Title 11 - Federal Elections is one of fifty titles comprising the United States Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), containing the principal set of rules and regulations issued by federal agencies regarding federal elections. It is available in digital and printed form, and can be referenced online using the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR). Read more

52 USC 30109: Enforcement, laws in effect on August 4, 2016

____________________________________________________

Title 11 CFR Federal Elections (LII)

11 CFR Chapter I - Federal Election Commission

11 CFR Chapter II - Election Assistance Commission

11 CFR sec 111 Compliance Federal Elections (GPO site)

Title 11 CFR - Federal Elections US Government Bookstore

Title 11 CFR - Federal Elections Electronic Code e-CFR

Title 11 CFR - Federal Elections CustomesMobile

Title 11 Federal Elections (CFR), January 1, 2016

National Archives GPO 556 pages PDF

Title 11 CFR Federal Elections Jan-2016.[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [2.0 MB]

Federal Elections Commission (FEC)

- FEC Legal Resources (beta)

- FEC Regulations (beta)

- FEC Commission Regulations

- FEC Search Final Advisory Opinions

- FEC Enforcement Matters

FEC Form 1 Statement of Organization (4 pages) (fillable)

FEC Form 2 Statement of Candidacy (1 page)

On Aug-06-2016 there are 1828 registered presidential candidates

In 2012 there were 417 registered presidential candidates

Federal Election Commission

Wikipedia

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent regulatory agency that was founded in 1975 by the United States Congress to regulate the campaign finance legislation in the United States. It was created in a provision of the 1974 amendment to the Federal Election Campaign Act. It describes its duties as "to disclose campaign finance information, to enforce the provisions of the law such as the limits and prohibitions on contributions, and to oversee the public funding of Presidential elections."[1] Read more

- The New York Times: Federal Election Commission

Tag: U.S. Code 52 USC 30109

Clinton and DNC at Risk for Campaign Finance Violations

With the WikiLeaks email scandal already causing the resignation of Democrat Party chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Hillary Clinton and the Democrat Party may now face legal risk regarding violations of campaign finance guidelines. Read more

Clinton and DNC at Risk for Campaign Finance Violations (full story)

Citizens United v. FEC

Wikipedia

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, No. 08-205, 558 U.S. 310 (2010), is a U.S. constitutional law and corporate law case dealing with the regulation of campaign spending by organizations. The United States Supreme Court held (5–4) that freedom of speech prohibited the government from restricting independent political expenditures by a nonprofit corporation. The principles articulated by the Supreme Court in the case have also been extended to for-profit corporations, labor unions and other associations[2][3]

In the case, the conservative non-profit organization Citizens United wanted to air a film critical of Hillary Clinton and to advertise the film during television broadcasts which was a violation of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, commonly known as the McCain–Feingold Act or "BCRA".[4] Section 203 of BCRA defined an "electioneering communication" as a broadcast, cable, or satellite communication that mentioned a candidate within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary, and prohibited such expenditures by corporations and unions. The United States District Court for the District of Columbia held that §203 of BCRA applied and prohibited Citizens United from advertising the film Hillary: The Movie in broadcasts or paying to have it shown on television within 30 days of the 2008 Democratic primaries.[1][5] The Supreme Court reversed this decision, striking down those provisions of BCRA that prohibited corporations (including nonprofit corporations) and unions from making independent expenditures and "electioneering communications".[4] The majority decision overruled Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990) and partially overruled McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003).[6] The Court, however, upheld requirements for public disclosure by sponsors of advertisements (BCRA §201 and §311). The case did not involve the federal ban on direct contributions from corporations or unions to candidate campaigns or political parties, which remain illegal in races for federal office.[7]

- U.S. Election Assistance Commission YouTube Channel

................U.S. Election Assistance Commission.................

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) was established by the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA). EAC is an independent, bipartisan commission charged with developing guidance to meet HAVA requirements, adopting voluntary voting system guidelines, and serving as a national clearinghouse of information on election administration. EAC also accredits testing laboratories and certifies voting systems, as well as audits the use of HAVA funds.

Other responsibilities include maintaining the national mail voter registration form developed in accordance with the National Voter Registration Act of 1993.

HAVA established the Standards Board and the Board of Advisors to advise EAC. The law also established the Technical Guidelines Development Committee to assist EAC in the development of voluntary voting system guidelines.

The four EAC commissioners are appointed by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. EAC is required to submit an annual report to Congress as well as testify periodically about HAVA progress and related issues. The commission also holds public meetings and hearings to inform the public about its progress and activities. Read more

Election Assistance Commission

Wikipedia

The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) is an independent agency of the United States government created by the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA). The Commission serves as a national clearinghouse and resource of information regarding election administration. It is charged with administering payments to states and developing guidance to meet HAVA requirements, adopting voluntary voting system guidelines, and accrediting voting system test laboratories and certifying voting equipment. It is also charged with developing and maintaining a national mail voter registration form. Read more

Florida Division of Elections (Department of State)

Florida Division of Elections (DOE/DOS)

R.A. Gray Building, Room 316

500 South Bronough Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0250

Phone: 850.245.6200

Fax: 850.245.6217

Email: DivElections@dos.myflorida.com

- Florida Department of State YouTube Channel

A compilation of the Election Laws of the State of Florida July 2016

election-laws.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [1.7 MB]

F.S. Title IX, Electors and Elections, Chapters 97-107

Florida election law is governed by the Florida Statutes

Title IX, Electors and Elections, Chapters 97-107

Chapter 97 Qualification and Registration of Electors

Part I: General Provisions (ss. 97.011-97.028)

Part II: Florida Voter Registration Act

(ss. 97.032-97.105)

Chapter 98 Registration Office, Officers, and Procedures

Chapter 99 Candidates

Chapter 100 General, Primary, Special, Bond, and Referendum

Elections

Chapter 101 Voting Methods and Procedure

Chapter 102 Conducting Elections and Ascertaining the Results

Chapter 103 Presidential Electors; Political Parties; Executive

Committees and Members

Chapter 104 Election Code: Violations; Penalties

Chapter 105 Nonpartisan Elections

Chapter 106 Campaign Financing

Chapter 107 Conventions for Ratifying or Rejecting Proposed

Amendments to Constitution of the United States

United States presidential election, 2016

United States presidential election, 2016

Wikipedia

The United States presidential election of 2016 is expected to be held on Tuesday, November 8, 2016. It will be the 58th quadrennial U.S. presidential election. Voters in the election will select presidential electors who in turn will elect a new President and Vice President of the United States. The incumbent president, Barack Obama, is ineligible to be elected to a third term due to term limits in the Twenty-second Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Background

Further information: United States presidential election § Procedure

Article Two of the United States Constitution provides that for a person to be elected and serve as President of the United States, the individual must be a natural-born citizen of the United States, at least 35 years old, and a resident of the United States for a period of no less than 14 years. Candidates for the presidency typically seek the nomination of one of the various political parties of the United States, in which case each party devises a method (such as a primary election) to choose the candidate the party deems best suited to run for the position. The party's delegates then officially nominate a candidate to run on the party's behalf.

Read more Wikipedia

United States presidential election

United States presidential election

Wikipedia

The election of President and Vice President of the United States is an indirect election in which citizens of the United States who are registered to vote in one of the fifty states or Washington, D.C. cast ballots for a set of members of the U.S. Electoral College, known as electors. These electors then in turn cast direct votes, known as electoral votes, for President and Vice President of the United States. The candidate who receives an absolute majority of electoral votes for President or Vice President is then elected to that office. If no candidate receives an absolute majority for President, the House of Representatives chooses the President; if no one receives a majority for Vice President, then the Senate chooses the Vice President. The Electoral College and its procedure is established in the U.S. Constitution by Article II, Section 1, Clauses 2 and 4; and the Twelfth Amendment (which replaced Clause 3 after it was ratified in 1804).

These presidential elections occur quadrennially, with registered voters casting their ballots on Election Day, which since 1845 has been the Tuesday after the first Monday in November,[1][2][3] coinciding with the general elections of various other federal, state, and local races. The next U.S. presidential election, the 58th quadrennial U.S. Presidential Election[4] is scheduled for November 8, 2016.

Under Article II, Section 1, Clause 2, each state legislature is allowed to designate a way of choosing electors. Thus, the popular vote on Election Day is conducted by the various states and not directly by the federal government. In other words, it is really an amalgamation of separate elections held in each state and Washington, D.C. instead of a single national election. Once chosen, the electors can vote for anyone, but – with rare exceptions like an unpledged elector or faithless elector – they vote for their designated candidates and their votes are certified by Congress, who is the final judge of electors, in early January. The presidential term then officially begins on Inauguration Day, January 20 (although the formal inaugural ceremony traditionally takes place on the 21st if the 20th is a Sunday).

The nomination process, consisting of the primary elections and caucuses and the nominating conventions, was never specified in the Constitution, and was instead developed over time by the states and the political parties. The primary elections are staggered generally between January and June before the general election in November, while the nominating conventions are held in the summer. This too is also an indirect election process, where voters from each U.S. state and Washington, D.C., as well as those in U.S. territories, cast ballots for a slate of delegates to a political party's nominating convention, who then in turn elect their party's presidential nominee. Each party's presidential nominee then chooses a vice presidential running mate to join with him or her on the same ticket, and this choice is rubber-stamped by the convention. Because of changes to national campaign finance laws since the 1970s regarding the disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns, presidential candidates from the major political parties usually declare their intentions to run as early as the spring of the previous calendar year before the election.[5] Thus, the entire modern presidential campaign and election process usually takes almost two years. Read more

_____________________________________________________

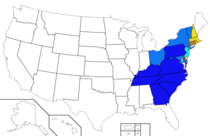

List of United States presidential electors, 2012

Wikipedia

This is a list of electors (members of the Electoral College) who cast ballots to elect the President of the United States and Vice President of the United States in the 2012 presidential election. There are 538 electors from the 50 states and the District of Columbia. While every state except Nebraska and Maine chooses the electors by statewide vote, many states require that one elector be designated for each congressional district. Except where otherwise noted, such designations refer to the elector's residence in that district rather than election by the voters of the district.[1] Read more

Political party

Wikipedia

A political party is a group of people who come together to contest elections and hold power in the government. They agree on some policies and programmes for the society with a view to promote the collective good or to further their supporters' interests.

While there is some international commonality in the way political parties are recognized, and in how they operate, there are often many differences, and some are significant. Many political parties have an ideological core, but some do not, and many represent very different ideologies than they did when first founded. In democracies, political parties are elected by the electorate to run a government. Many countries have numerous powerful political parties, such as Germany and India and some nations have one-party systems, such as China. The United States is a two-party system, with its two most powerful parties being the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Read more

Political parties in the United States

Wikipedia

Throughout most of its history, American politics have been dominated by a two-party system. However, the United States Constitution has always been silent on the issue of political parties; at the time it was signed in 1787, there were no parties in the nation. Indeed, no nation in the world had voter-based political parties. The need to win popular support in a republic led to the American invention of voter-based political parties in the 1790s.[1] Americans were especially innovative in devising new campaign techniques that linked public opinion with public policy through the party.[2]

Political scientists and historians have divided the development of America's two-party system into five eras.[3] The first two-party system consisted of the Federalist Party, who supported the ratification of the Constitution, and the Democratic-Republican Party or the Anti-Federalists, who opposed the powerful central government, among others, that the Constitution established when it took effect in 1789.[4] The modern two-party system consists of the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Several third parties also operate in the U.S., and from time to time elect someone to local office.[5] The largest third party since the 1980s is the Libertarian Party. Read more

First Party System

Wikipedia

The First Party System is a model of American politics used in history and political science to periodize the political party system existing in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824.[1] It featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: the Federalist Party, created largely by Alexander Hamilton, and the rival Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican Party formed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and usually called at the time the "Republican Party." The Federalists were dominant until 1800, while the Republicans were dominant after 1800.

In an analysis of the contemporary party system, Jefferson wrote on February 12, 1798:

Two political Sects have arisen within the U. S. the one believing that the executive is the branch of our government which the most needs support; the other that like the analogous branch in the English Government, it is already too strong for the republican parts of the Constitution; and therefore in equivocal cases they incline to the legislative powers: the former of these are called federalists, sometimes aristocrats or monocrats, and sometimes Tories, after the corresponding sect in the English Government of exactly the same definition: the latter are stiled republicans, Whigs, jacobins, anarchists, dis-organizers, etc. these terms are in familiar use with most persons.[2]

Both parties originated in national politics, but soon expanded their efforts to gain supporters and voters in every state. The Federalists appealed to the business community, the Republicans to the planters and farmers. By 1796 politics in every state was nearly monopolized by the two parties, with party newspapers and caucuses becoming especially effective tools to mobilize voters.

The Federalists promoted the financial system of Treasury Secretary Hamilton, which emphasized federal assumption of state debts, a tariff to pay off those debts, a national bank to facilitate financing, and encouragement of banking and manufacturing. The Republicans, based in the plantation South, opposed a strong executive power, were hostile to a standing army and navy, demanded a strict reading of the Constitutional powers of the federal government, and strongly opposed the Hamilton financial program. Perhaps even more important was foreign policy, where the Federalists favored Britain because of its political stability and its close ties to American trade, while the Republicans admired the French and the French Revolution. Jefferson was especially fearful that British aristocratic influences would undermine republicanism. Britain and France were at war from 1793–1815, with only one brief interruption. American policy was neutrality, with the federalists hostile to France, and the Republicans hostile to Britain. The Jay Treaty of 1794 marked the decisive mobilization of the two parties and their supporters in every state. President George Washington, while officially nonpartisan, generally supported the Federalists and that party made Washington their iconic hero.[3]

The First Party System ended during the Era of Good Feelings (1816–1824), as the Federalists shrank to a few isolated strongholds and the Republicans lost unity. In 1824–28, as the Second Party System emerged, the Republican Party split into the Jacksonian faction, which became the modern Democratic Party in the 1830s, and the Henry Clay faction, which was absorbed by Clay's Whig Party. Read more

Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000)

Bush v. Gore

Wikipedia

Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000), is the United States Supreme Court decision that resolved the dispute surrounding the 2000 presidential election. Three days earlier, the Court had preliminarily halted the Florida recount that was occurring. Eight days earlier, the Court unanimously decided the closely related case of Bush v. Palm Beach County Canvassing Board, 531 U.S. 70 (2000).

In a per curiam decision, the Court ruled that there was an Equal Protection Clause violation in using different standards of counting in different counties and ruled that no alternative method could be established within the time limit set by Title 3 of the United States Code (3 U.S.C.), § 5 ("Determination of controversy as to appointment of electors"), which was December 12.[1] The vote regarding the Equal Protection Clause was 7–2, and regarding the lack of an alternative method was 5–4.[2] Three concurring justices also asserted that the Florida Supreme Court had violated Article II, § 1, cl. 2 of the Constitution, by misinterpreting Florida election law that had been enacted by the Florida Legislature.

The decision allowed Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris's previous certification of George W. Bush as the winner of Florida's 25 electoral votes to stand. Florida's votes gave Bush, the Republican candidate, 271 electoral votes, one more than the required 270 electoral votes to win the Electoral College and defeat Democratic candidate Al Gore, who received 266 electoral votes (a District of Columbia elector abstained). Media organizations subsequently analyzed the ballots, and under the strategy that Al Gore pursued at the beginning of the Florida recount — filing suit to force hand recounts in four predominantly Democratic counties — Bush would have kept his lead, according to the ballot review conducted by the consortium. The study also found that a statewide tally that did not reject ballots containing overvotes (where a voter hole-punches multiple candidates but writes out the name of their intended candidate) would have resulted in Gore emerging as the victor by 60 to 171 votes.

Virginia law binding delegates to vote for Trump violates First Amendment, federal judge rules

ABA Journal Daily News

By Debra Cassens Weiss

Posted Jul 12, 2016 10:14 am CDT

A federal judge on Monday enjoined a Virginia law that requires delegates to vote on the first ballot for the winner of the state primaries—which would require GOP delegates to vote for Donald Trump.

U.S. District Judge Robert Payne of Richmond, Virginia, agreed with lawyer and GOP delegate Carroll "Beau" Correll that the law imposing criminal penalties for noncompliance violated Correll’s First Amendment rights of political speech and association, report the Wall Street Journal Law Blog, NBC News, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, the Washington Post and the Huffington Post. Correll supports U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas.

Payne said (PDF) that the Virginia law conflicts with Republican Party Rule 16, which allocates delegates based on a proportional vote. Payne did not reach a decision on whether two other Republican Party rules allow for "conscience voting" at the convention, saying that theory is not ripe for decision.

Correll tells NBC about 20 states have laws binding delegates to candidates. He asserted the Trump campaign is "morbidly humiliated" by the decision. "They put all their chips on the table and they lost all of them—if I were them I’d go hide in a closet in Trump Tower," he said.

The Trump campaign saw a victory in portions of the ruling finding Rule 16 is in effect and questioning the conscience-voting theory. Two groups are trying to modify the convention rules to free delegates from required votes. Read more

Are Trump delegates bound to support

Trump at the convention?

Washington Post/Volokh Conspiracy

By Jonathan H. Adler

June 25, 2016

Donald Trump is the presumptive Republican nominee for president because he won a majority of delegates awarded in state primaries, caucuses and conventions. If every delegate votes in accordance with the primary results, Trump will be declared the Republican candidate at the GOP convention in Cleveland. But what if, in their heart of hearts, a majority of delegates do not actually support Trump? Are they bound? Not necessarily.

Existing GOP convention rules provide that delegates are bound by the results of their respective state primaries, caucuses or conventions. Yet as Eric O’Keefe and David Rivkin pointed out in the Wall Street Journal, these rules expire before the delegates must cast their votes.

Rule 16 of the Republican National Committee says primaries will be used to "allocate and bind" delegates. But that rule expires at the convention’s start. Though a majority of delegates could vote to adopt a binding rule at the convention, that’s unlikely. It has happened only once before, in 1976, when loyalists of President Ford sought to block the insurgency of Ronald Reagan.

But what about state law? Some 20 states have laws on the books requiring state delegates to vote in accordance with the results of state primaries, caucuses or conventions. Yet these laws raise some interesting constitutional questions.

A lawsuit filed last week in federal court challenges the Virginia law that purports to bind Virginia delegates. According to the complaint and memorandum in support of the plaintiff’s motion for a temporary restraining order, insofar as Virginia law compels delegates to vote in accordance with the state primary results, it violates the First Amendment. The plaintiff, Carroll Boston Correll Jr., seeks an injunction barring prosecution so that he may vote his conscience at the convention. As his complaint begins:

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees delegates to the Republican Party’s and Democratic Party’s national conventions the right to vote their conscience, free from government compulsion, when participating in the selection of their party’s presidential nominee. Nonetheless, Virginia law acts to strip them of that right, imposing criminal penalties on delegates who vote for anyone other than the primary winner on the first ballot at a national convention. That law cannot be sustained under the First Amendment or as a legitimate exercise of Virginia’s authority under the United States Constitution

As O’Keefe and Rivkin explain further:

State laws that purport to bind delegates can’t be enforced without violating the First Amendment. A political party is a private association whose members join together to further their shared beliefs through electoral politics, and they have a right to choose their representatives. The government has no business telling parties how to select their candidates or leaders: That would be a serious infringement of the rights to free association and speech.

Such infringements can be upheld only if they are narrowly tailored to advance a compelling government interest. Yet states have no valid interest, much less a compelling one, in binding delegates. As the Supreme Court recognized in Cousins v. Wigoda (1975): "The States themselves have no constitutionally mandated role in the great task of the . . . selection of Presidential and Vice-Presidential candidates."

As Correll’s filings elaborate, the Supreme Court has repeatedly found that various state laws burden the associational rights of political parties and their members. These precedents support the principle that it is up to a political party — and not state legislatures — to determine how to select a party’s nominees.

If Correll’s suit is successful, it would eliminate one of the legal obstacles to replacing Trump as the Republican nominee. Given the decline of Trump’s poll numbers, and the candidate’s continued insistence on saying things that alienate key portions of the electorate (including many lifelong Republicans), dumping Trump is an option GOP convention delegates might want to have.

Jonathan H. Adler teaches courses in constitutional, administrative, and environmental law at the Case Western University School of Law, where he is the inaugural Johan Verheij Memorial Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Business Law and Regulation.

- Jonathan H. Adler Wikipedia

Correll - Filed Complaint.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [986.6 KB]

Correll TRO PI Motion Memo FINAL.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [125.8 KB]

United States presidential primary

Voters checking in at a 2008 Washington state Democratic caucus held at Eckstein Middle School in Seattle

Voters checking in at a 2008 Washington state Democratic caucus held at Eckstein Middle School in Seattle

United States presidential primary

Wikipedia

For the ongoing presidential primaries, see Democratic Party presidential primaries, 2016 and Republican Party presidential primaries, 2016.

The series of presidential primary elections and caucuses held in each U.S. state and territory forms part of the nominating process of United States presidential elections. The United States Constitution has never specified the process; political parties have developed their own procedures over time. Some states hold only primary elections, some hold only caucuses, and others use a combination of both. These primaries and caucuses are staggered, generally beginning in either late-January or early-February, and ending about mid-June before the general election in November. State and local governments run the primary elections, while caucuses are private events that are directly run by the political parties themselves. A state's primary election or caucus is usually an indirect election: instead of voters directly selecting a particular person running for President, they determine the number of delegates each party's national convention will receive from their respective state. These delegates then in turn select their party's presidential nominee.

Each party determines how many delegates it allocates to each state. Along with those "pledged" delegates chosen during the primaries and caucuses, state delegations to both the Democratic and Republican conventions also include "unpledged" delegates who have a vote. For Republicans, they consist of the three top party officials who serve At Large from each state and territory. Democrats have a more expansive group of unpledged delegates called "superdelegates", who are party leaders and elected officials (PLEO). If no single candidate has secured an absolute majority of delegates (including both pledged and unpledged), then a "brokered convention" occurs: all pledged delegates are "released" after the first round of voting and are able to switch their allegiance to a different candidate, and then additional rounds take place until there is a winner with an absolute majority.

The staggered nature of the presidential primary season allows candidates to concentrate their resources in each area of the country one at a time instead of campaigning in every state simultaneously. In some of the less populous states, this allows campaigning to take place on a much more personal scale. However, the overall results of the primary season may not be representative of the U.S. electorate as a whole: voters in Iowa, New Hampshire and other less populous states which traditionally hold their primaries and caucuses in late-January/February usually have a major impact on the races, while voters in California and other large states which traditionally hold their primaries in June generally end up having no say because the races are usually over by then. As a result, more states vie for earlier primaries, known as "front-loading", to claim a greater influence in the process. The national parties have used penalties and awarded bonus delegates in efforts to stagger the system over broadly a 90 day window. Where state legislatures set the primary or caucus date, sometimes the out-party in that state has endured penalties in the number of delegates it can send to the national convention.

Democratic Party presidential primaries, 2016

Wikipedia

The 2016 Democratic Party presidential primaries and caucuses were a series of electoral contests taking place within all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia and five U.S. territories, occurring between February 1 and June 14, 2016. Sanctioned by the Democratic Party, these elections were designed to select the 4,051 delegates to send to the Democratic National Convention, which will select the Democratic Party's nominee for President of the United States in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. An extra 718 unpledged delegates (714 votes), or "superdelegates", are appointed by the party independently of the primaries' electoral process. The convention will also approve the party's platform and vice-presidential nominee. The Democratic nominee will challenge other presidential candidates in national elections to succeed President Barack Obama at noon on January 20, 2017, following his two terms in office.

A total of six major candidates entered the race starting April 12, 2015, when former Secretary of State and New York Senator Hillary Clinton formally announced her second bid for the presidency. She was followed by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, former Governor of Maryland Martin O'Malley, former Governor of Rhode Island Lincoln Chafee, former Virginia Senator Jim Webb and Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig. There was some speculation that incumbent Vice President Joe Biden would also enter the race, but he chose not to run. A draft movement was started to encourage Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren to seek the presidency, but Warren declined to run. Prior to the Iowa caucuses on February 1, 2016, Webb and Chafee both withdrew after consistently polling below 2%.[2] Lessig withdrew after the rules of a debate were changed such that he would no longer qualify to participate.[3]

Clinton won Iowa by the closest margin in the history of the state's Democratic caucus. O'Malley suspended[c] his campaign after a distant third-place finish, leaving Clinton and Sanders the only two candidates. The electoral battle turned out to be more competitive than expected, with Sanders winning the New Hampshire primary while Clinton scored victories in the Nevada caucuses and South Carolina primary. On four different Super Tuesdays, Clinton secured numerous important wins in each of the nine largest states including California, New York, Florida, and Texas, while Sanders scored various victories in between.[5]

On June 6, 2016, the Associated Press and NBC News stated that Clinton had become the presumptive nominee after reaching the required number of delegates, including both pledged and unpledged delegates (superdelegates), to secure the nomination. In doing so, she had become the first woman to ever be the presumptive nominee of any major political party in the United States.[6] On June 7, Clinton officially secured a majority of pledged delegates after winning in the California and New Jersey primaries.[7] President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden and Senator Elizabeth Warren formally endorsed Clinton on June 9, 2016.[8][9] Bernie Sanders confirmed in June 2016 that he would vote for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in a general election.[10] However, he has stated that he will not make an endorsement until the convention.[11] Read more

Republican Party presidential primaries, 2016

Wikipedia

The 2016 Republican Party presidential primaries and caucuses were a series of electoral contests taking place within all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories, occurring between February 1 and June 7. Sanctioned by the Republican Party, these elections are designed to select the 2,472 delegates to send to the Republican National Convention, who will select the Republican Party's nominee for President of the United States in the 2016 election. The delegates will also approve the party platform and vice-presidential nominee. The presumptive Republican nominee is Donald Trump.

A total of 17 major candidates entered the race starting March 23, 2015, when Senator Ted Cruz of Texas was the first to formally announce his candidacy: former Governor Jeb Bush of Florida, retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson of Maryland, Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey, businesswoman Carly Fiorina of California, former Governor Jim Gilmore of Virginia, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, former Governor Mike Huckabee of Arkansas, former Governor Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, Governor John Kasich of Ohio, former Governor George Pataki of New York, Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky, former Governor Rick Perry of Texas, Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, former Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, businessman Donald Trump of New York and Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin. This was the largest presidential primary field for any political party in American history.[2]

Prior to the Iowa caucuses on February 1, Perry, Walker, Jindal, Graham and Pataki withdrew due to low polling numbers. Despite leading many polls in Iowa, Trump came in second to Cruz, after which Huckabee, Paul and Santorum withdrew due to poor performances at the ballot box. Following a sizable victory for Trump in the New Hampshire primary, Christie, Fiorina and Gilmore abandoned the race. Bush withdrew after scoring fourth place to Trump, Rubio and Cruz in South Carolina. On Super Tuesday, March 1, 2016, Rubio won his first contest in Minnesota, Cruz won Alaska, Oklahoma and his home state of Texas, while Trump won seven states. Failing to gain traction, Carson suspended[a] his campaign a few days later.[4] On March 15, 2016, nicknamed "Super Tuesday II", Kasich won his first contest in Ohio and Trump won five primaries including Florida. Rubio suspended his campaign after losing his home state,[5] but he retained a large share of his delegates for the national convention.[6]

From March 15 to May 3, only three candidates remained in the race: Trump, Cruz and Kasich. Cruz won most delegates in four Western contests and in Wisconsin, keeping a credible path to denying Trump the nomination on first ballot with 1,237 delegates. In due course, however, Trump scored landslide victories in New York and five North-Eastern states in April, before taking every delegate in the Indiana primary of May 3. Without any further chances of forcing a contested convention, Cruz suspended his campaign[7] and Trump was declared the presumptive Republican nominee by Republican National Committee chairman Reince Priebus on the evening of May 3.[8] Kasich dropped out the next day.[9] After winning the Washington primary and gaining support from unbound North Dakota delegates on May 26,[10] Trump passed the threshold of 1,237 delegates required to guarantee his nomination.[11] Read more

Electoral College (United States)

Electoral College (United States)

Wikipedia

The United States Electoral College is the institution that elects the President and Vice President of the United States every four years. Citizens of the United States do not directly elect the president or the vice president; instead, these voters directly elect designated intermediaries called "electors," who almost always have pledged to vote for particular presidential and vice presidential candidates (though unpledged electors are possible) and who are themselves selected according to the particular laws of each state. Electors are apportioned to each of the 50 states as well as to the District of Columbia (also known as Washington, D.C.). The number of electors in each state is equal to the number of members of Congress to which the state is entitled,[1] while the Twenty-third Amendment grants the District of Columbia the same number of electors as the least populous state, currently three. Therefore, there are currently 538 electors, corresponding to the 435 Representatives and 100 Senators, plus the three additional electors from the District of Columbia. The Constitution bars any federal official, elected or appointed, from being an elector.

Except for the electors in Maine and Nebraska, electors are elected on a "winner-take-all" basis.[2] That is, all electors pledged to the presidential candidate who wins the most votes in a state become electors for that state. Maine and Nebraska use the "congressional district method", selecting one elector within each congressional district by popular vote and selecting the remaining two electors by a statewide popular vote.[3] Although no elector is required by federal law to honor a pledge, there have been very few occasions when an elector voted contrary to a pledge.[4][5] The Twelfth Amendment, in specifying how a president and vice president are elected, requires each elector to cast one vote for president and another vote for vice president.

The candidate who receives an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270) for the office of president or of vice president is elected to that office. The Twelfth Amendment provides for what happens if the Electoral College fails to elect a president or vice president. If no candidate receives a majority for president, then the House of Representatives will select the president, with each state delegation (instead of each representative) having only one vote. If no candidate receives a majority for vice president, then the Senate will select the vice president, with each senator having one vote. On four occasions, most recently in 2000, the Electoral College system has resulted in the election of a candidate who did not receive the most popular votes in the election.[6][7]

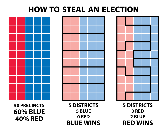

Gerrymandering

Wikipedia

In the process of setting electoral districts, gerrymandering is a practice intended to establish a political advantage for a particular party or group by manipulating district boundaries. The resulting district is known as a gerrymander (/'d??ri?mænd?r/); however, that word can also refer to the process. The term gerrymandering has negative connotations.

In addition to its use achieving desired electoral results for a particular party, gerrymandering may be used to help or hinder a particular demographic, such as a political, ethnic, racial, linguistic, religious, or class group, such as in U.S. federal voting district boundaries that produce a majority of constituents representative of African-American or other racial minorities, known as "majority-minority districts". Gerrymandering can also be used to protect incumbents. Read more

Gerrymandering in the United States

Wikipedia

Gerrymandering in the United States has been practiced since the founding of the country to strengthen the power of particular political interests within legislative bodies. Partisan gerrymandering is commonly used to increase the power of a political party. In some instances, political parties collude to protect incumbents by engaging in bipartisan gerrymandering. After racial minorities were enfranchised, some jurisdictions engaged in racial gerrymandering to weaken the political power of racial minority voters, while others engaged in racial gerrymandering to strengthen the power of minority voters. Throughout the 20th century, courts have grappled with the legality of these types of gerrymandering and have devised different standards for the different types of gerrymandering. Various legal and political remedies have emerged to prevent gerrymandering, including court-ordered redistricting plans, redistricting commissions, and alternative voting systems that do not depend on drawing boundaries for single-member electoral districts. Read more

Separation of powers

Wikipedia

The separation of powers, often imprecisely used interchangeably with the trias politica principle,[1] is a model for the governance of a state (or who controls the state). The model was first developed in ancient Greece. Under this model, the state is divided into branches, each with separate and independent powers and areas of responsibility so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with the powers associated with the other branches. The typical division of branches is into a legislature, an executive, and a judiciary. It can be contrasted with the fusion of powers in a parliamentary system where the executive and legislature (and sometimes parts of the judiciary) are unified.

Separation of powers, therefore, refers to the division of responsibilities into distinct branches to limit any one branch from exercising the core functions of another. The intent is to prevent the concentration of power and provide for checks and balances.

Main article: Separation of powers under the United States Constitution

In the United States Constitution, Article 1 Section I gives Congress only those "legislative powers herein granted" and proceeds to list those permissible actions in Article I Section 8, while Section 9 lists actions that are prohibited for Congress. The vesting clause in Article II places no limits on the Executive branch, simply stating that, "The Executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America."[26] The Supreme Court holds "The judicial Power" according to Article III, and it established the implication of Judicial review in Marbury v. Madison under the Marshall court.[27] The federal government refers to the branches as "branches of government", while some systems use "government" to describe the executive. The Executive branch has attempted to claim power arguing for separation of powers to include being the Commander in Chief of a standing army since the American Civil War, executive orders, emergency powers and security classifications since World War II, national security, signing statements, and the scope of the unitary executive. Read more

Separation of powers under the United States Constitution

Wikipedia

Separation of powers is a political doctrine originating in the writings of Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws where he urged for a constitutional government with three separate branches of government. Each of the three branches would have defined abilities to check the powers of the other branches. This idea was called separation of powers. This philosophy heavily influenced the writing of the United States Constitution, according to which the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches of the United States government are kept distinct in order to prevent abuse of power. This United States form of separation of powers is associated with a system of checks and balances.

During the Age of Enlightenment, philosophers such as John Locke advocated the principle in their writings, whereas others, such as Thomas Hobbes, strongly opposed it. Montesquieu was one of the foremost supporters of separating the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. His writings considerably influenced the opinions of the framers of the United States Constitution.

Strict separation of powers did not operate in The United Kingdom, the political structure of which served in most instances[citation needed] as a model for the government created by the U.S. Constitution.[citation needed] Under the UK Westminster system, based on parliamentary sovereignty and responsible government, Parliament (consisting of the Sovereign (King-in-Parliament), House of Lords and House of Commons) was the supreme lawmaking authority. The executive branch acted in the name of the King ("His Majesty's Government"), as did the judiciary. The King's Ministers were in most cases members of one of the two Houses of Parliament, and the Government needed to sustain the support of a majority in the House of Commons. One minister, the Lord Chancellor, was at the same time the sole judge in the Court of Chancery and the presiding officer in the House of Lords. Therefore, it may be seen that the three branches of British government often violated the strict principle of separation of powers, even though there were many occasions when the different branches of the government disagreed with each other. Some U.S. states did not observe a strict separation of powers in the 18th century. In New Jersey, the Governor also functioned as a member of the state's highest court and as the presiding officer of one house of the New Jersey Legislature. The President of Delaware was a member of the Court of Appeals; the presiding officers of the two houses of the state legislature also served in the executive department as Vice Presidents. In both Delaware and Pennsylvania, members of the executive council served at the same time as judges. On the other hand, many southern states explicitly required separation of powers. Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia all kept the branches of government "separate and distinct." Read more

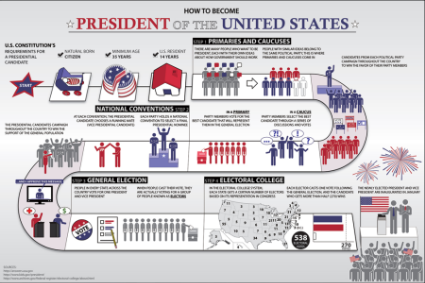

........How to Become President of The United States........

How to Become the US President: A Step-by-Step Guide

From the 2012 Presidential Election

1. Meet Eligibility Guidelines Set by the US Constitution

2. Test the Water: Pre-Candidacy Process

3. Declare Candidacy & File Applications with Federal Election Commission

4. Fundraise and Campaign

5. Party Primaries, Caucuses, and Delegates

6. Party Conventions

7. General Election Campaign: The Final Candidates

8. Election Day: Winning the Popular and Electoral Votes

1. Meet Eligibility Guidelines Set by the US Constitution

Article II of the United States Constitution establishes the Executive Branch of the Government, including the President, Vice-President, and other executive officers. Within Article II, rules are set as to who can become President and how a President is elected:

Article II

Section 1. The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his office during the term of four years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same term, be elected, as follows:

...No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the office of President neither shall any person be eligible to that office who shall not have attained to the age of thirty five years, and been fourteen Years a resident within the United States.

United States Constitution, Sep. 17, 1787 Read more