......................How the Courts Failed Germany.....................

A Forum on the Law: How the Courts Failed Germany, Thursday, September 6, 2012. By Dr. William Meinecke Jr., Education Division, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Be patient with the film, it takes a long time to load.

- A Forum on the Law: How the Courts Failed Germany, November 16, 2010. Dr. William Meinecke Jr.

- Forum on the Law: How the Courts Failed Germany Staff Report August 10, 2012

- Law, Justice and the Holocaust How the Courts Failed Germany, Facebook page, Dr. William Meinecke Lecture

Be patient with the film, it takes a long time to load.

The courts failed Germany, a failure that led to The Holocaust. How the rule of law failed, and the lawyers, judges, and courts that facilitated The Holocaust failed Germany is profiled here.

How the Courts Failed Germany Judicial Independence Track

Law, Justice and the Holocaust How the Courts Failed Germany, 1933-1945

Law, Justice, and The Holocaust 84p.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [30.5 MB]

How the Courts Failed Germany, Judicial [...]

Adobe Acrobat document [1.9 MB]

Law, Justice, and The Holocaust 9p.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [1.4 MB]

How the Courts Failed Germany, Family La[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [164.9 KB]

The Auschwitz Files

Spiegel Online International

By Klaus Wiegrefe

August 28, 2014

In February, German prosecutors conducted a wave of raids targeting former SS concentration camp guards. It was hoped the proceedings could help make up for decades of inaction. Instead, they will likely mark the latest chapter in the German judiciary's shameful approach to the Holocaust.

It was a carefully coordinated campaign. Criminal investigators from the German states of North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria, Hesse and Baden-Württemberg all struck at the same time, at 9 a.m. on Feb. 19 of this year. The investigators, driving civilian vehicles, drove up to residences in 12 locations and presented the suspects with search warrants. The officials had previously determined whether their targets had firearm or explosives licenses.

The suspects, of course, were not expected to put up any resistance. The youngest was 88 and the oldest almost 100. Nevertheless, three of the accused -- in Wiernsheim, Gerlingen and Freiburg -- were temporarily taken into custody. Read more

Guardians of the Constitution - Germany's Constitutional Court Turns 60 | People & Politics

Germany still untangling Nazis' legal legacy

In this Oct. 5, 2015 photo German Minister of Justice, Heiko Maas, looks on after an interview with the news agency 'The Associated Press' at the ministry in Berlin, Germany. (AP Photo/Michael Sohn)

In this Oct. 5, 2015 photo German Minister of Justice, Heiko Maas, looks on after an interview with the news agency 'The Associated Press' at the ministry in Berlin, Germany. (AP Photo/Michael Sohn)

AP Interview: Germany still untangling Nazis'

legal legacy

By FRANK JORDANS

October 6, 2015

ERLIN (AP) — Germany's justice ministry is embarked on a wide-ranging effort to examine the influence that the Nazis had on the country's legal system, including the role some German officials played in preventing former Nazis from being prosecuted after the war.

The project, 70 years after the end of World War II, comes amid a fresh push to bring surviving Nazi war criminals to justice.

Two trials of alleged death camp guards would have been impossible until recently due to legal hurdles and the existence of a network of former Nazis who worked as lawyers, prosecutors and judges after the war.

"Too many who bore guilt covered for each other," Justice Minister Heiko Maas told The Associated Press in an interview. "Even at the start of the 1960s, 80 percent of the judges at the Federal Court of Justice had been judges under the Nazis. That illustrates the extent to which the German justice system failed."

Efraim Zuroff, the head Nazi hunter for the Simon Wiesenthal Center, cautiously welcomed the move.

"The stakes are certainly not as high as they once were," Zuroff told The AP on Tuesday. "Having said that, this is a very, very important historical inquiry that I think will have an important impact on the way German society views the judicial effort and the whole question of bringing Nazis to justice."

"There's no question that the initial decades could be classified as a very serious failure. Not a complete failure but a serious failure," he added.

Among the obstacles to prosecuting former Nazis was that German law required proof of direct involvement in a killing for a murder charge — the only crime not covered by the statute of limitations.

This meant that thousands of people who played an important role in the Holocaust weren't prosecuted.

That changed in 2011 when a German court accepted Munich prosecutors' new legal reasoning in the case of John Demjanjuk. They argued that Demjanjuk was a guard at Sobibor, a death camp whose sole purpose was murder, so even if there was no evidence he participated in a specific crime he could be convicted as an accessory for helping the camp function.

The conviction unleashed an 11th-hour wave of new investigations, even though it wasn't legally binding because Demjanjuk, who always denied serving as a death camp guard, died before his appeal could be heard.

"German jurisprudence took a long time to conclude that it wasn't necessary to play a personal, concrete, active part but (that it was sufficient) if someone had worked elsewhere to make the death camp function in the first place," said Maas. "I think that's absolutely right."

Though most suspects are now in their 90s, holding them to account is important for survivors, victims' families and the German state, Maas said.

"It's never too late for justice," he said.

After the high-profile Nuremberg trials of top Nazis and some lesser-known tribunals carried out by the victorious Allied powers, Germany's judicial system was left to deal with other Nazi-era crimes on its own.

Maas said it was important to convey to a new generation of law students how post-war Germany initially failed in that task.

"The point of this project is to acknowledge the greatest mistake of Germany's post-war legal system, which was that the justice system — which between 1933 and 1945 was nothing but a stooge of the Nazis — didn't help to atone for the Nazi crimes after World War II in the young Federal Republic," he said.

One of the few who spoke out at the time was Fritz Bauer, a German-Jewish lawyer who became the attorney general for Hesse state in 1956. Bauer was so distrustful of the German authorities and its many former Nazis that when he learned of Adolf Eichmann's whereabouts in Argentina, he chose to tip off Israel's Mossad rather than risk that one of the key figures in the Holocaust might be warned by friends in the German justice system.

"Bauer's work is dramatized in two recent feature films, one of which — Labyrinth of Lies" — has been selected to represent Germany for the foreign language Oscar next year.

Maas said several laws tinged by the past are also being re-examined.

One is Germany's law on murder, which was shaped by Roland Freisler, who held a senior position in the Nazi justice ministry and later became president of Nazi Germany's People's Court where he oversaw many prominent trials of opposition figures.

The law, passed in 1941, has long been considered problematic because it draws on the Nazi idea that murder is a crime committed by a certain type of person, such as someone acting out of "lowly motivations" or killing someone in a "sneaky" fashion.

This has led to cases where a man who repeatedly beats his wife, eventually killing her, was convicted of manslaughter, while an abused woman who kills her husband in his sleep is convicted of murder.

"We don't want the language of the Nazis in our criminal code anymore, especially not in one of its central parts that deals with murder and manslaughter," said Maas.

Another law in the process of being changed concerns the handling of looted art. The issue gained prominence two years ago when it emerged that a reclusive art collector, Cornelius Gurlitt, had more than 1,200 valuable artworks — some of them taken from Jews persecuted by the Nazis.

A draft law would shift more of the burden of proof to the owners of suspected Nazi loot to demonstrate they acquired it in good faith. Read more

Andreas Voßkuhle, German Constitutional Court President | Journal Interview

Some of the Nazi lawyers and judges who failed the courts, failed Germany and ultimately failed all humanity.

Nazi lawyer Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick

Wikipedia

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of

the Nazi Party, who served as Reich Minister of the

Interior in the Hitler Cabinet from 1933 to

1943[2] and as the last governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. After the end of World War II, he was tried for war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials and executed. Read more

Nazi lawyer Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Wikipedia

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 1903 – 16 October 1946) was an Austrian-born senior official of Nazi Germany during World War II. An Obergruppenführer (general) in the Schutzstaffel (SS), between January 1943 and May 1945 he held the offices of Chief of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, Reich Main Security Office) and President of the ICPC, later to become Interpol. He was the highest-ranking member of the SS to face trial at the first Nuremberg Trials. He was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and executed. Read more

At the Nuremberg Trials, Kaltenbrunner was charged with conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war-crimes and crimes against humanity. The most notable witness in this trial was Rudolf Hoss, the camp commander of the Auschwitz concentration camp. Kaltenbrunner was hanged October 16, 1946.

Nazi lawyer Wilhelm Stuckart

Wikipedia

Wilhelm Stuckart (16 November 1902 – 15 November 1953) was a Nazi Party lawyer and official, a state secretary in the German Interior Ministry[1] and later, a convicted war criminal. Read more

Nazi lawyer Hans Globke

Wikipedia

Hans Josef Maria Globke (10 September 1898 – 13 February 1973) was a high-ranking public servant after World War II in the Federal Republic of Germany. His crass antisemitic activities as a high-profile civil servant and jurist before and specially during the Nazi time resulted in controversies after the war that troubled his protector and only supervisor Konrad Adenauer, who had recruited him to serve in his administration. Read more

Before the death camps - - Einsatzgruppen

The Killing Fields - Einsatzgruppen - The "other" Holocaust

Before the extermination camps even started operation, the Nazis were already shooting hundreds of thousands of men, women and children all over Eastern Europe.

Einsatzgruppen, Wikipedia

Overlooked Millions: Non-Jewish Victims of the Holocaust

Karen Silverstrim, MA Candidate, University of Central Arkansas

An Introduction to the Einsatzgruppen an essay by Yale F. Edeiken

Jewish Virtual Library, The Holocaust: The Einsatzgruppen

Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team Einsatzgruppen

- Reserve Police Battalion 101 Wikipedia

- Reserve Police Battalion 101 JewishVirtualLibrary.org

- The Men Who Pulled the Triggers NYT by Walter Reich

Nazi lawyer Gerhard Klopfer

Wikipedia

Gerhard Klopfer (February 18, 1905 - January 29, 1987) was an official of the Nazi Party and assistant to Martin

Bormann in the Office of the (Nazi) Party Chancellery. He studied law and economics and in 1931 became a judge in Düsseldorf, Germany. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, he joined the Nazi Party

and the SA (Sturmabteilung) along with the Gestapo (Secret State Police) the following year.

In 1935, he became a member of Rudolf Hess's staff and the SS (Schutzstaffel) with the honorary SS rank of Oberführer (Brigadier General). In 1938, he became responsible for the seizing of Jewish

businesses for questions about mixed marriages between Gentile and Jewish Germans and general questions about occupation of foreign states.

As State Secretary of the Parteikanzlerei (Party Chancellery), Klopfer represented Bormann, who was head of the Parteikanzlei, at the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942 in which the details of

the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" were formalized, policies that were to culminate in the Holocaust.

As the Red Army closed in on Berlin in 1945, Klopfer fled the city. He was captured and imprisoned and was charged with war crimes but was released for lack of evidence.

After the war Klopfer became a tax advisor in the city of Ulm (Baden-Württemberg). He was allowed to resume the practice of law in 1956. Klopfer was the last surviving attendee of the Wannsee Conference, dying in 1987. Obituary NYT

GERHARD KLOPFER, GENERAL IN THE SS - NYT[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [37.9 KB]

Nazi lawyer Erich Neumann

Erich Neumann (politician)

Wikipedia

Erich Neumann (b. 31 May 1892[1] — d. 1948[2] or 23 March 1951[1]) was a Nazi politician.

Neumann was born in Forst (Lausitz) into a Protestant family. His father was a factory owner.

After receiving his Abitur, Neumann studied law and economics at the universities of Freiburg, Leipzig and Halle. He served in World War I and reached the rank of First Lieutenant (Oberleutnant). In 1920, he served as governmental civil servant (Regierungsassessor) in the Prussian Ministry of the Interior, and thereafter in the Essen District Office.

Neumann became Senior Executive Officer (Regierungsrat) in the Prussian Ministry of Commerce in 1923.[1][2] In 1927/28, he became District President (Landrat) in Freystadt (Lower Silesia), then served as Ministerial Junior Assistant Secretary (Ministerialrat) again in the Prussian Ministry of Commerce. In September 1932, he was appointed Permanent Secretary (Ministerialdirektor) in the Prussian Ministry of State, where he was in charge of administrative reforms.[2]

Neumann joined the Nazi Party in May 1933, four months after Adolf Hitler took power. He joined the SS in 1934, being commissioned as a Major (Sturmbannführer).[1][2] In 1936, he was appointed the director of the Foreign Currency department of the Office of the Plenipotentiary for the Four Year Plan. By 1938, Neumann was promoted to undersecretary and attended Hermann Göring's meeting about the "Aryanisation" of the German economy. He represented the Ministries of Economy, Labour, Finances, Food, Transport and Armaments and Ammunition at the 1942 Wannsee Conference. Neumann requested that Jewish workers in firms essential to the war effort not to be deported for the time being. Between August 1942 and May 1945, Neumann was the general manager of the German Potassium Syndicate.

He was interned and interrogated by the Allies in 1945 after the war but released due to poor health in 1948.[1][2] Some sources quote his death being in the same year,[2] however, the German Federal Archives record him as dying three years later in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, on 23 March 1951.[1] Read more

Nazi lawyer Josef Bühler

Josef Bühler

Wikipedia

Josef Bühler (also referred to as Joseph Buehler) (16 February 1904 – 22 August 1948) was a secretary and deputy governor to the Nazi-controlled General Government in Kraków during World War II.

Background

Bühler was born in Bad Waldsee into a Catholic family of 12 children, his father being a baker. After obtaining his degree in law he received an appointment to work under Hans Frank, a legal advisor to Adolf Hitler and NSDAP (The Nazi Party). He was also elected as a member of the Weimar and Nazi Reichstags.

Nazi career

Hans Frank was appointed Minister of Justice for Bavaria in 1933. Bühler became a member of NSDAP on 1 April 1933, according to his own testimony at the Nuremberg Trials, and was appointed administrator of the Court of Munich. In 1935 he became district chief attorney.

Main article: General Government administration

In 1938 Hans Frank, now Reich Minister without portfolio, put him in charge of his cabinet office. After the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in September 1939, Frank was appointed Governor-General for the occupied Polish territories and Bühler accompanied him to Kraków to take up the post of State Secretary of the General Government, also serving as Frank's deputy. He was given the honorary rank of SS-Brigadeführer by SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler around this time.

Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution

Bühler attended the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942 as the representative from the Governor-General's office. During this conference – which discussed the imposition of the 'Final Solution of the Jewish Question in the German Sphere of Influence in Europe' – Bühler stated to the other conference attendees the importance of solving 'the Jewish Question in the General Government as quickly as possible'.[1] Read More

Nazi lawyer Rudolf Lange

Wikipedia

Rudolf Lange was born to a Protestant family in Weißwasser, Prussian Silesia, in 1910. His father was a railway construction supervisor. Lange studied law in the University of Jena. He received a doctorate in law in 1933, and was recruited by the Gestapo office of Halle. He joined the SA in November 1933. In 1936 Lange joined the SS. As a mid-level Gestapo official, Lange rose rapidly. Lange was called to the Wannsee Conference by Heydrich in January 1942. Along with Adolf Eichmann, the recording secretary of the conference, Lange as a SS-Major was the lowest ranking of the present SS officers. Heydrich however viewed Lange's first-hand experience in conducting the mass murder of deported Jews as valuable for the conference. Instead of Lange, Heydrich could have invited either Karl Jäger or Erich Ehrlinger, who commanded the SiPO and SD in Lithuania and Belarus respectively, and were responsible for similar massacres. He ultimately chose Lange, because Riga was the main deportation destination, and also because Lange's law doctorate made him to be seen more intellectual than either Jäger or Ehrlinger. Read more

Roland Freisler (30/10/1893 - 03/02/1945) was a German jurist, whose career came to its climax during the dictatorship of the Nazis. From August 1942 until his death he was president of the People's Court, the highest court of the Nazi state for political criminal matters.

Nazi judge Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler

Wikipedia

Roland Freisler (30 October 1893 – 3 February 1945) was a prominent Nazi lawyer and judge. He was State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice and President of the People's Court (Volksgerichtshof), which was set up outside constitutional authority. This court handled cases of political actions against Adolf Hitler's National-Socialist regime by conducting a series of infamous trials. Read more

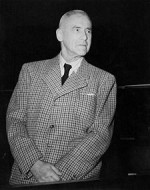

Nazi judge Curt Rothenberger

Wikipedia

Curt Ferdinand Rothenberger (born 30 June 1896 in Cuxhaven - died 1 September 1959 in Hamburg) was a German jurist

and leading figure in the Nazi Party.

In the immediate aftermath of the Nazi seizure of power Rothenberger was part of an unofficial group within the Nazi Party, led by Hans Frank and Roland Freisler, the aim

of which was to transform the legal profession by installing loyal party men in leading positions within the judiciary. Rothenberger was appointed Senator of Justice in Hamburg and set about putting

these ideas into practice, insisting that all judges had to be "100% national socialist" and had to be trusted by party officials. Where this was not the case the judges faced summary dismissal.

Jewish judges were removed from office as early March 1933 under Rothenberger's orders. Read more

Nazi judge Otto Thierack

Wikipedia

Otto Georg Thierack (19 April 1889 – 22 November 1946) Nazi jurist and politician.

Thierack was born in Wurzen in Saxony. He took part in the First World War from 1914 to 1918 as a volunteer, reaching the rank of lieutenant. He suffered a face injury

and was decorated with the Iron Cross, second class. After the war ended, he resumed his interrupted law studies and ended them in 1920 with his Assessor (junior lawyer) examination. In the same

year, he was hired as a court Assessor in Saxony.

On 1 August 1932, Thierack joined the Nazi Party. After the Nazis seized power in 1933, he managed within a very short time to rise high in the ranks from a prosecutor to

President of the People's Court (Volksgerichtshof). The groundwork on which this rise was built was not merely that Thierack had been a Nazi Party member, but rather also that he had been leader of

the National Socialist jurists' organization, the so-called Rechtswahrerbund.

On 12 May 1933, having been appointed Saxony's justice minister, it was Thierack's job to "Nazify" justice, which was a part of the Nazis' Gleichschaltung that he had to

put into practice in Saxony. After going through several mid-level professional posts, he became Vice President of the Reich Court in 1935 and in 1936 President of the Volksgerichtshof, which had

been newly founded in 1934. He held this job, interrupted as it was by two stints in the armed forces, until 1942, when he was succeeded in the position by Roland Freisler.

On 20 August 1942, Thierack assumed the office of Reich Minister of Justice. He introduced the monthly Richterbriefe in October 1942, in which were presented model – from

the Nazi leaders' standpoint – decisions, with names left out, upon which German jurisprudence was to be based. He also introduced the so-called Vorschauen and Nachschauen ("previews" and

"inspections"). After this, the higher state court presidents, in proceedings of public interest, had at least every fortnight to discuss with the public prosecutor's office and the State Court

President – who had to pass this on the responsible criminal courts – how a case was to be judged before the court's decision.

Thierack not only made penal prosecution of all unpopular persons and groups harsher. "Antisocial" convicts on the whole were much more often turned over to the SS. This

usually meant Jews, Poles, Russians, and Gypsies. Soon afterwards, though, he utterly forwent any pretense of legality and simply began handing these people over to the SS. Thierack came to an

understanding with Heinrich Himmler that certain categories of prisoners were to be, to use their words, "annihilated through work". Ever since coming to office as Reich Minister of Justice in August

1942, Thierack had seen to it that the lengthy paperwork involved in clemency proceedings for those sentenced to death was greatly shortened.

At Thierack's instigation, the execution shed at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin was outfitted with eight iron hooks in December 1942 so that several people could be put to

death at once, by hanging (there had already been a guillotine there for quite a while). At the mass executions beginning on 7 September 1943, it also happened that some prisoners were hanged "by

mistake". Thierack simply covered up these mistakes and demanded that the hangings continue.

After the Allies arrested him, Thierack committed suicide in Sennelager, Paderborn, by poisoning before he could be brought before the court at the Nuremberg Judges'

Trial. Read more

Nazi judge Franz Schlegelberger

Wikipedia

Louis Rudolph Franz Schlegelberger (23 October 1876 – 14 December 1970) was State Secretary in the German Reich Ministry of Justice (RMJ) and served

awhile as Justice Minister during the Third Reich. He was the highest-ranking defendant at the Judges' Trial in Nuremberg.

At the Nuremberg Judges' Trial Schlegelberger was one of the main accused. He was sentenced to life in prison for conspiracy to perpetrate war crimes and crimes against

humanity.

In the reasons given for the judgment, it says:

‘…that Schlegelberger supported the pretension of Hitler in his assumption of power to deal with life and death in disregard of even the pretense of

judicial process. By his exhortations and directives, Schlegelberger contributed to the destruction of judicial independence. It was his signature on the decree of 7 February 1942 which imposed upon

the Ministry of Justice and the courts the burden of the prosecution, trial, and disposal of the victims of Hitler’s Night and Fog. For this he must be charged with primary

responsibility.

‘He was guilty of instituting and supporting procedures for the wholesale persecution of Jews and Poles. Concerning Jews, his ideas were less brutal

than those of his associates, but they can scarcely be called humane. When the "final solution of the Jewish question" was under discussion, the question arose as to the disposition of half-Jews. The

deportation of full Jews to the East was then in full swing throughout Germany. Schlegelberger was unwilling to extend the system to half-Jews.’

In 1950 the 74-year-old Schlegelberger was released owing to incapacity. For years afterward, he drew a monthly pension of DM 2,894 (for comparison, the average monthly

income in Germany at that time was DM 535). Schlegelberger then lived in Flensburg until his death. Read

more

Nazi judge Josef Altstötter

Wikipedia

Josef Altstötter (4 January 1892 Bad Griesbach (Rottal), Lower Bavaria - 13 November 1979, Nuremberg) was a high

ranking official in the German Ministry of Justice under the Nazi Regime. Following World War II, he was tried by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal as a defendant in the Judges' Trial, where he was

acquitted of the most serious charges, but was found guilty of a lesser charge of membership in a criminal organization.

After attending elementary and high school in Landshut, Altstötter began the study of law in 1911 Law in Munich and Erlangen. This was interrupted by his participation in

the First World War, where he was awarded the Iron Cross First and Second Class.

Altstötter completed his studies in Munich in 1920, passed the state jurisprudence examination and began work in 1921 as deputy judge in the Bavarian Justice Department

to. In 1927 he worked in the Reich Ministry of Justice. In 1933, he moved to the Supreme Court for Leipzig and finally in 1936 into Reich Labour Court.

From 1939 to 1942 he was with the Wehrmacht. From January 1943 he was back in the Reich Ministry of Justice (Division VI:Civil Law and Justice), where he was appointed in

May 1943 chief of the civil law and procedure division ("Reichministerialdirektor"), and remained there throughout the Second World War. He was awarded the Golden Party Badge for service to the Nazi

party.

Part of Altstötter's department included the Nuremberg racial laws enacted to isolate Jews from German life and deprive them of civil rights. His office also had

responsibility for revising the German inheritance and family law by, so that after death, the property of Jews would not go to their children, but by law would be forfeited to the German

government. Read more

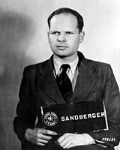

Martin Sandberger, age 98, last high ranking Nazi

Sandberger studied law at the University of Tübingen, earned the highest grade in nine years in the state bar examination.

Spiegel Online International

By WALTER MAYR

April 15, 2010

Spiegel Conducts the Last and Only Interview with Martin Sandberger

Sandberger was the last living member of the leadership of the special commandos in Himmler's murdering system. He used to appear, whether in Tallinn or Verona, as a demigod in the field-gray uniform of the SS. A total of 5,643 executions were carried out under his command on Estonian soil during the first year alone of the Nazi occupation. At the height of the power bestowed upon him by Hitler, all it took was Sandberger's signature to order the execution, behind the Eastern Front, of what he called "a subject of absolutely no value to the ethnic community." Read more

He was a Nazi officer on the front lines of the Holocaust, sentenced to death at Nuremberg -- yet with the help of powerful friends, he walked free. For decades, Martin Sandberger lived in Germany undisturbed. Shortly before his death, SPIEGEL found him in a retirement home. A final meeting with a criminal.

He must have been convinced that no wanted to find him anymore. His name, Dr. Martin Sandberger, was printed for all to see on the mailbox next to the gray door of his apartment in a Stuttgart retirement home, until he died on March 30, 2010. more

The Quiet Death of a Nazi_ Martin Sandbe[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [64.6 KB]

Nazi lawyer Martin Sandberger

Martin Sandberger

Wikipedia

Martin Sandberger (17 August 1911 – 30 March 2010[1]) was an SS Standartenführer (Colonel) and commander of Sonderkommando 1a of the Einsatzgruppe, as well as commander of the Sicherheitspolizei and SD in Estonia. He played an important role in the mass murder of the Jews in the Baltic states. He was also responsible for the arrest of Jews in Italy, and their deportation to Auschwitz concentration camp. Sandberger was the second-highest official of Einsatzgruppe A to be tried, and convicted.[2]

Background and early career

Martin Sandberger was born in Charlottenburg, Berlin as a son of a director of IG Farben. Sandberger studied law at the Universities of München, Köln, Freiburg and Tübingen.[3] At the age of 20 he joined the NSDAP and the SA. From 1932 - 1933 Sandberger was a Nazi student activist and student leader in Tübingen. On 8 March 1933 Sandberger and fellow student Erich Ehrlinger raised the Nazi flag in front of the main building at the University of Tübingen.[4] (Like Sandberger, Ehrlinger would take charge of an Einsatzkommando in 1941, and in so doing, commit thousands of murders.)

By 1935 he had obtained his doctorate degree.[5] As a functionary of the Nazi student League he eventually became a university inspector. In 1936 he became an enlisted member of the SS and under the command of Gustav Adolf Scheel for the SD in Württemberg.

He began a career with the SD and by 1938 he had risen to the rank of SS Sturmbannführer (major). Sandberger worked as an assistant judge in the Interior Administration of Württemberg and became a government councillor in 1937.[3] Read more

This scene from Conspiracy shows Dr. Kritzinger in opposition to Heydrich’s plan for the Final Solution. Unfortunately playback has been disabled on this video. Click here to watch on YouTube.

Reinhard Heydrich led the Wannsee Conference that created the Final Solution. Heydrich died June 4, 1942 in Operation Anthropoid.

Little Lady, Big World

A Journey from Manchester to Chiang Mai

April 16, 2014

I spent a day at Auschwitz-I and Auschwitz-II Birkenau. No words of mine can do this place justice, so here are some pictures instead