............................Federal Judicial Complaints.......................

Filing a Complaint of Judicial Misconduct or Judicial Disability Against A Federal Judge.

Has a Federal Judgeship Become a Safe Haven for Coordinated Wrongdoing? By Dr. Richard Cordero, Esq. Judicial Discipline Reform

Dr. Cordero's work is profiled at the end of this page

Judicial Conduct & Disability

Under the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act and the Rules for Judicial-Conduct and Judicial-Disability Proceedings, anyone can file a complaint alleging a federal judge has committed misconduct or has a disability.

The Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980, 28 U.S.C. §§ 351-364 establishes a process by which any person can file a complaint alleging a federal judge has engaged in "conduct prejudicial to the effective and expeditious administration of the business of the courts" or has become, by reason of a mental or physical disability, "unable to discharge all the duties" of the judicial office.

The Rules for Judicial-Conduct and Judicial-Disability Proceedings, as amended on September 17, 2015, provide mandatory and nationally uniform provisions governing the substantive and procedural aspects of misconduct and disability proceedings under the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act.

The judicial conduct and disability review process cannot be used to challenge the correctness of a judge’s decision in a case. A judicial decision that is unfavorable to a litigant does not alone establish misconduct or a disability. An attorney can explain any rights you have as a litigant to seek review of a judicial decision.

For more information, please visit the following links:

- Frequently Asked Questions about filing a judicial conduct or disability complaint against a federal judge.

- Graphical Overview of the process for filing a judicial conduct or disability complaint against a federal judge.

Judicial Conduct & Disability - US Eleventh Circuit COA

Codes of Conduct and related sources of authority provide standards of behavior for judges and others in the federal court family. The Judicial Conduct and Disability Act allows complaints alleging that a federal judge has engaged in "conduct prejudicial to the effective and expeditious administration of the business of the courts" or has become, by reason of a temporary or permanent condition, "unable to discharge the duties" of the judicial office.

Congress has created a procedure that permits any person to file a complaint in the courts about the behavior of federal judges—but not about the decisions federal judges make in deciding cases. Below is a link to the rules that explain what may be complained about, who may be complained about, where to file a complaint, and how the complaint will be processed. There is also a link to the form you may use.

Almost all complaints in recent years have been dismissed because they do not follow the law about such complaints. The law says that complaints about judges’ decisions and complaints with no evidence to support them must be dismissed. If you are a litigant in a case and believe the judge made a wrong decision—even a very wrong decision—you may not use this procedure to complain about the decision. An attorney can explain the rights you have as a litigant to seek review of a judicial decision.

- Addendum Three (Rules for Judicial-Conduct and Judicial-Disability Proceedings adopted by the Judicial Conference of the United States, with Eleventh Circuit Judicial Conduct and Disability Rules) (9/15)

Final Orders on Complaints of Judicial Misconduct or Disability - US Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals

RulesAddendum03MAY16.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [293.1 KB]

FormJudicialComplaintSEP15.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [50.0 KB]

28 U.S. Code Chapter 16 - COMPLAINTS AGAINST JUDGES AND JUDICIAL DISCIPLINE - LII Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law

Court Resources

A judicial misconduct or disability complaint against a federal judge must be filed in the appropriate court office, as described in Rule 7 of the Rules for Judicial-Conduct and Judicial-Disability Proceedings. Please visit the website of the appropriate court office for additional information.

- First Circuit (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Puerto Rico)

- Second Circuit (Connecticut, New York, Vermont)

- Third Circuit (Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virgin Islands)

- Fourth Circuit (Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia)

- Fifth Circuit (Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas)

- Sixth Circuit (Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, Tennessee)

- Seventh Circuit (Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin)

- Eighth Circuit (Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota)

- Ninth Circuit (Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington)

- Tenth Circuit (Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, Wyoming)

- Eleventh Circuit (Alabama, Florida, Georgia)

- District of Columbia Circuit (District of Columbia)

Fix the Court Calls on Judicial Conference to Be

More Transparent About Its Operations

September 13, 2016

The Judicial Conference of the United States, led by Chief Justice John Roberts (right) and comprising some of the nation’s top federal judges, is meeting in D.C. for its semiannual summit, yet scant information about the roles and responsibilities of this body, the composition of its committees or the work it was planning to accomplish has been released publicly.

"The judges who sit on the Judicial Conference are tasked with making important decisions on federal judiciary policy, from rules of evidence and civil procedure to directives on travel and codes of conduct," Fix the Court executive director Gabe Roth said. "Yet there is no online database of all of the committees, their roles and who sits on them, and it is nearly impossible to locate their work on various matters until months after the fact, if at all." Read more

Judicial Conference of the United States - US Courts

Governance & the Judicial Conference

Judicial Conference

The Judicial Conference of the United States is the national policy-making body for the federal courts. The current name took effect when Congress enacted Section 331 of Title 28 of the United States Code. Before that, the body was known as the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges from its creation in 1922. Read more

The Judicial Conference of the United States is the national policy-making body for the federal courts.

Membership

The Chief Justice of the United States is the presiding officer of the Judicial Conference. Membership is comprised of the chief judge of each judicial circuit, the Chief Judge of the Court of International Trade, and a district judge from each regional judicial circuit.

Judicial Conference of the United States

Articles related to the Judicial Conference of the United States, the policy making body for the U.S. Courts.

Conference Moves to Enhance Judges' Accountability,

Ethical Compliance

Published onSeptember 19, 2006

Contact: David Sellers, 202-502-2600

The Judicial Conference of the United States today approved two policies aimed at aiding and enhancing judges' compliance with established ethical obligations.

The Conference voted to require all federal courts to useconflict-checking computer software to identify cases in which judges may have a financial conflict of interest and should disqualify themselves. It also approved a new policy requiring greater disclosure by both those who provide privately funded educational programs for judges and the judges who attend such programs.

Judicial Conference of the United States

Articles related to the Judicial Conference of the United States, the policy making body for the U.S. Courts.

Amended Rules Effective December 1, 2014

A number of amendments to the Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure and official bankruptcy forms became effective December 1, 2014. The changes to the Federal Rules follow recommendations by the Judicial Conference of the United States, review by the Supreme Court, and consideration by Congress. The amendments affect the Appellate, Civil, Criminal, Bankruptcy and Evidence Rules.

The Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure govern the conduct of trials, appeals, and cases under Title 11 of the United States Code. In the Rulemaking process, it usually takes two to three years for a proposal to be enacted as a rule.

The Judicial Conference Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure reviews the findings of its advisory committees, and determines whether to recommend Judicial Conference approval of the proposed rules amendments. If the Conference approves the amendments, it transmits them to the Supreme Court. The Court considers the proposals and, if it concurs, officially promulgates the revised rules by order before May 1, to take effect no earlier than December 1 of the same year, unless Congress enacts legislation to reject, modify, or defer the pending rules.

Current Rules of Practice & Procedure (some, but not all

below)

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Federal Rules of Evidence

Forms Accompanying the Rules of Procedure and Evidence

Code of Conduct for United States Judges

Code of Conduct for United States Judges, U.S. Courts website

Federal judges must abide by the Code of Conduct for United States Judges, a set of ethical principles and guidelines adopted by the Judicial Conference of the United States. The Code of Conduct provides guidance for judges on issues of judicial integrity and independence, judicial diligence and impartiality, permissible extra-judicial activities, and the avoidance of impropriety or even its appearance.

Judges may not hear cases in which they have either personal knowledge of the disputed facts, a personal bias concerning a party to the case, earlier involvement in the case as a lawyer, or a financial interest in any party or subject matter of the case.

Many federal judges devote time to public service and educational activities. They have a distinguished history of service to the legal profession through their writing, speaking, and teaching. This important role is recognized in the Code of Conduct, which encourages judges to engage in activities to improve the law, the legal system, and the administration of justice.

Code of Conduct for United States Judges

Judicial Disqualification An Analysis of Federal Law (Second Edition)

Federal Judicial Center 2010

Recusal: Analysis of Case Law Under 28 U.S.C. §§ 455 & 144 (2002) Federal Judicial Center 2002

Due Process and Judicial Disqualification: The Need for Reform

Gabriel D. Serbulea Due Process and Judicial Disqualification: The Need for Reform, 38 Pepp. L. Rev. 4 (2011) Available at:

http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol38/iss4/4

Judicial Disqualification An Analysis of[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [1'013.6 KB]

Recusal, Analysis of Case Law Under 28 U[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [243.3 KB]

Due Process and Judicial Disqualificatio[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [3.4 MB]

Code of Conduct For Judicial Employees

Code of Conduct For Judicial Employees

The Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees includes the ethical canons that apply to judicial employees and provides guidance on their performance of official duties and engagement in a variety of outside activities. The judiciary has several codes of conduct, approved by the Judicial Conference of the United States, that serve as primary sources of ethical guidance for judges and judicial employees.

Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees (PDF)

Guide to Judicial Policy

Vol. 2: Ethics and Judicial Conduct

Pt. A: Code of Conduct

Ch 3: Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees

Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees.p[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [87.4 KB]

Judicial Conference of the United States - Wikipedia

Judicial Conference of the United States

Wikipedia

The Judicial Conference of the United States, formerly known as Conference of Senior Circuit Judges, was created by the United States Congress in 1922 with the principal objective of framing policy guidelines for administration of judicial courts in the United States. The Conference derives its authority from 28 U.S.C. § 331, which states it is headed by the Chief Justice of the United States and consists of the Chief Justice, the chief judge of each court of appeals federal regional circuit, a district court judge from various federal judicial districts, and the chief judge of the United States Court of International Trade.[1] Read more

Judicial council (United States) - Wikipedia

Judicial council (United States)

Wikipedia

Judicial councils are panels of the United States federal courts that are charged with making "necessary and appropriate orders for the effective and expeditious administration of justice" within their circuits.[1] Among their responsibilities is judicial discipline, the formulation of circuit policy, the implementation of policy directives received from the Judicial Conference of the United States, and the annual submission of a report to the Administrative Office of the United States Courts on the number and nature of orders entered during the year that relate to judicial misconduct.[2] Each US judicial circuit has a judicial council, which consists of the chief judge of the circuit and an equal number of circuit judges and district judges of the circuit.[3]

Judicial discipline

The judicial discipline process of US federal judges is initiated by the filing of a complaint by any person alleging that a judge has engaged in conduct "prejudicial to the effective and expeditious administration of the business of the courts, or alleging that such judge is unable to discharge all the duties of the office by reason of mental or physical disability."[4] If the chief judge of the circuit does not dismiss the complaint or conclude the proceedings, then he or she must promptly appoint himself or herself, along with equal numbers of circuit judges and district judges, to a special committee to investigate the facts and allegations in the complaint. The committee must conduct such investigation as it finds necessary and then expeditiously file a comprehensive written report of its investigation with the judicial council of the circuit involved. Upon receipt of such a report, the judicial council of the circuit involved may conduct any additional investigation it deems necessary, and it may dismiss the complaint.[5]

If a judge who is the subject of a complaint holds his or her office during good behavior, action taken by the judicial council may include certifying disability of the judge. The judicial council may also, in its discretion, refer any complaint under 28 U.S.C. § 351, along with the record of any associated proceedings and its recommendations for appropriate action, to the Judicial Conference. The Judicial Conference may exercise its authority under the judicial discipline provisions as a conference, or through a standing committee appointed by the Chief Justice. Read more

The Judiciary Act of 1789: "An Act to establish the Judicial Courts of the United States." 1 Stat. 73.

The Judiciary Act of 1789: "An Act to establish the Judicial Courts of the United States." 1 Stat. 73. September 24, 1789.

Federal Judicial Center

Landmark Judicial Legislation

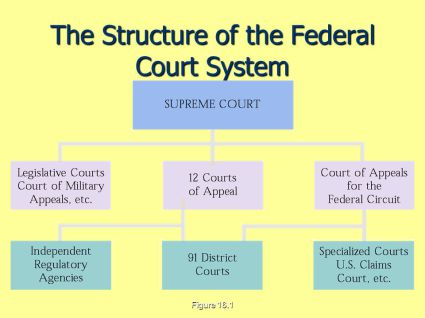

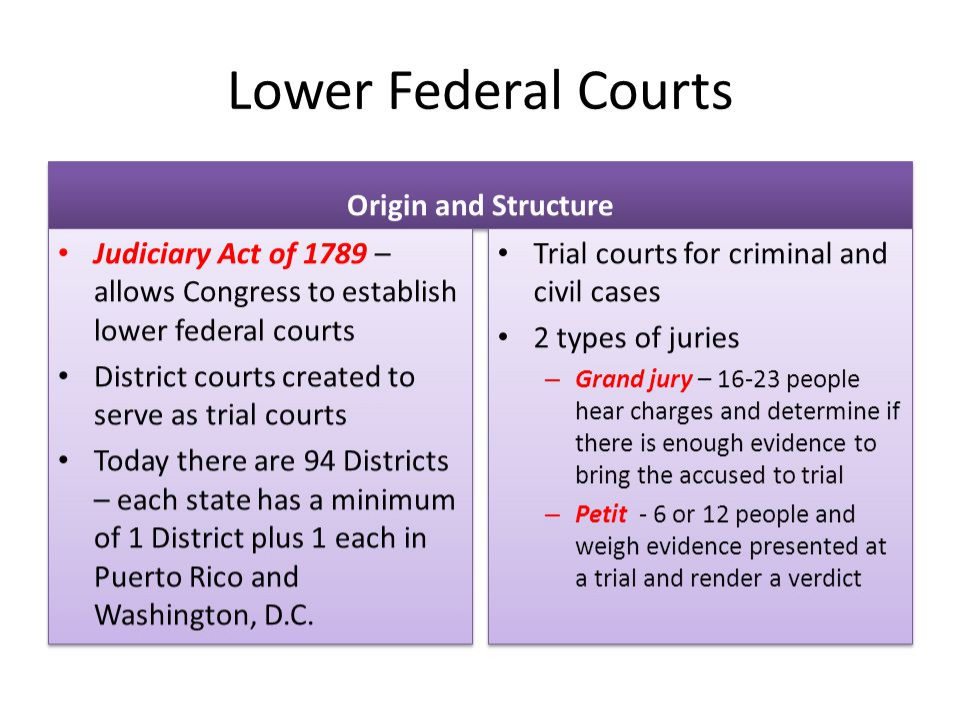

In the Judiciary Act of 1789, the First Congress provided the detailed organization of a federal judiciary that the Constitution had sketched only in general terms. Acting on its constitutional authority to establish inferior courts, the Congress instituted a three-part judiciary. The Supreme Court consisted of a Chief Justice and five associate justices. In each state and in Kentucky and Maine (then part of other states), a federal judge presided over a United States district court, which heard admiralty and maritime cases and some other minor cases. The middle tier of the judiciary consisted of United States circuit courts, which served as the principal trial courts in the federal system and exercised limited appellate jurisdiction. Two Supreme Court justices and the local district judge presided in the circuit courts. Under the practice known as "circuit riding," each justice was assigned to one of three geographical circuits and traveled to the designated meeting places within the districts of that circuit. Read more

The Judiciary Act; September 24, 1789, 1 Stat. 73.

An Act to Establish the Judicial Courts of the United States.

Yale Law School, The Avalon Project

Lillian Goldman Law Library

SECTION 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices, any four of whom shall be a quorum, and shall hold annually at the seat of government two sessions, the one commencing the first Monday of February, and the other the first Monday of August. That the associate justices shall have precedence according to the date of their commissions, or when the commissions of two or more of them bear date on the same day, according to their respective ages. Read more

Judiciary Act of 1789

Library of Congress

Primary Documents in American History

The Judiciary Act of 1789, officially titled "An Act to Establish the Judicial Courts of the United States," was signed into law by President George Washington on September 24, 1789. Article III of the Constitution established a Supreme Court, but left to Congress the authority to create lower federal courts as needed. Principally authored by Senator Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, the Judiciary Act of 1789 established the structure and jurisdiction of the federal court system and created the position of attorney general. Although amended throughout the years by Congress, the basic outline of the federal court system established by the First Congress remains largely intact today. Read more

Judiciary Act of 1789

Wikipedia

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, 1 Stat. 73) was a United States federal statute adopted on September 24, 1789, in the first session of the First United States Congress.

It established the federal judiciary of the United States.[3][4][5][6] Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution prescribed that the "judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and such inferior Courts" as Congress saw fit to establish. It made no provision for the composition or procedures of any of the courts, leaving this to Congress to decide.[7]

The existence of a separate federal judiciary had been controversial during the debates over the ratification of the Constitution. Anti-Federalists had denounced the judicial power as a potential instrument of national tyranny. Indeed, of the ten amendments that eventually became the Bill of Rights, five (the fourth through the eighth) dealt primarily with judicial proceedings. Even after ratification, some opponents of a strong judiciary urged that the federal court system be limited to a Supreme Court and perhaps local admiralty judges. The Congress, however, decided to establish a system of federal trial courts with broader jurisdiction, thereby creating an arm for enforcement of national laws within each state.

Legislative history

The Senate Journal records that Richard Henry Lee (AA-VA) reported the judiciary bill out of committee on June 12, 1789;[2] Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut was its chief author.[8] The bill passed the Senate 14–6 on July 17, 1789, and the House of Representatives then debated the bill in July and August 1789. The House passed an amended bill 37–16 on September 17, 1789. The Senate struck four of the House amendments and approved the remaining provisions on September 19, 1789. The House passed the Senate's final version of the bill on September 21, 1789.

President George Washington signed the Judiciary Act of 1789 into law on September 24, 1789 and promptly submitted his nominations to fill the offices created by the Act. Among the nominees were John Jay for Chief Justice of the United States; John Rutledge, William Cushing, Robert H. Harrison, James Wilson, and John Blair, Jr. as Associate Justices; Edmund Randolph for Attorney General; and myriad district judges, United States Attorneys, and United States Marshals for Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia.[2][9]

Provisions of the Act

The Act set the number of Supreme Court justices at six: one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. The Supreme Court was given exclusive original jurisdiction over all civil actions between states, or between a state and the United States, as well as over all suits and proceedings brought against ambassadors and other diplomatic personnel; and original, but not exclusive, jurisdiction over all other cases in which a state was a party and any cases brought by an ambassador. The Court was given appellate jurisdiction over decisions of the federal circuit courts as well as decisions by state courts holding invalid any statute or treaty of the United States; or holding valid any state law or practice that was challenged as being inconsistent with the federal constitution, treaties, or laws; or rejecting any claim made by a party under a provision of the federal constitution, treaties, or laws.

The Act also created 13 judicial districts within the 11 states that had then ratified the Constitution (North Carolina and Rhode Island were added as judicial districts in 1790, and other states as they were admitted to the Union). Each state comprised one district, except for Virginia and Massachusetts, each of which comprised two. Massachusetts was divided into the District of Maine (which was then part of Massachusetts) and the District of Massachusetts (which covered modern-day Massachusetts). Virginia was divided into the District of Kentucky (which was then part of Virginia) and the District of Virginia (which covered modern-day West Virginia and Virginia).

This Act established a circuit court and district court in each judicial district (except in Maine and Kentucky, where the district courts exercised much of the jurisdiction of the circuit courts). The circuit courts, which comprised a district judge and (initially) two Supreme Court justices "riding circuit," had original jurisdiction over serious crimes and civil cases of at least $500 involving diversity jurisdiction or the United States as plaintiff in common law and equity. The circuit courts also had appellate jurisdiction over the district courts. The single-judge district courts had jurisdiction primarily over admiralty cases, petty crimes, and suits by the United States for at least $100. Notably, the federal trial courts had not yet received original federal question jurisdiction.

Congress authorized all people to either represent themselves or to be represented by another person. The Act did not prohibit paying a representative to appear in court.

Congress authorized persons who were sued by citizens of another state, in the courts of the plaintiff's home state, to remove the lawsuit to the federal circuit court. The power of removal, and the Supreme Court's power to review state court decisions where federal law was at issue, established that the federal judicial power would be superior to that of the states.

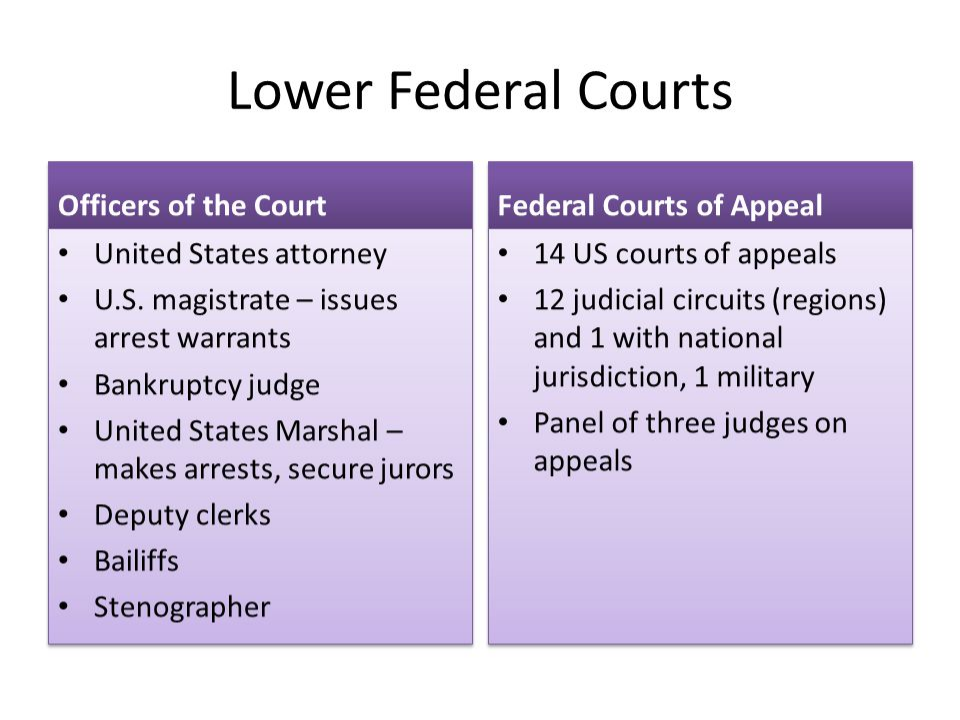

The Act created the Office of Attorney General, whose primary responsibility was to represent the United States before the Supreme Court. The Act also created a United States Attorney and a United States Marshal for each judicial district.[6]

The Judiciary Act of 1789 included the Alien Tort Statute, now codified as 28 U.S.C. § 1350, which provides jurisdiction in the district courts over lawsuits by aliens for torts in violation of the law of nations or treaties of the United States.

Judicial review

Main articles: Judicial review and Marbury v. Madison

A clause granting the Supreme Court the power to issue writs of mandamus under its original jurisdiction was declared unconstitutional by Marbury v. Madison (1803) (5 U.S. 137), one of the seminal cases in American law. The Supreme Court held that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act was unconstitutional because it purported to enlarge the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court beyond that permitted by the Constitution. In Marbury, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress cannot pass laws that are contrary to the Constitution, and that it is the role of the judicial system to interpret what the Constitution permits. Thus, the Judiciary Act of 1789 was the first act of Congress to be partially invalidated by the Supreme Court.[10][11] Read more

Has a Federal Judgeship Become a Safe Haven for Coordinated Wrongdoing?

By Dr. Richard Cordero, Esq.

Dr. Richard Cordero, Esq.

Ph.D., University of Cambridge, England

M.B.A., University of Michigan Business School

D.E.A., La Sorbonne, Paris

59 Crescent Street, Brooklyn, NY 11208

Dr.Richard.Cordero.Esq@gmail.com

tel. (718) 827-9521

Synopsis of an Investigative Journalism Proposal

Where the leads in evidence already gathered in a cluster of federal cases would be pursued in a Watergate-like Follow the money! investigation to answer the question:

Has a Federal Judgeship Become a Safe Haven for Coordinated Wrongdoing? with links to references at http://Judicial-Discipline-Reform.org/Follow_money/DrCordero-journalists.pdf

This is a poignant question, for it casts doubt on the integrity of the government branch that should incarnate respect for the law and high ethical values. What makes

it a realistic question worth investigating is the fact that since the Judicial Conduct Act judges

are charged with the duty to discipline themselves. Anybody with a complaint against a federal judge must file it with the chief circuit judge, whose decision may be reviewed by the circuit council. But according to the official statistics, judges systematically dismissed 99.86% of the 7,977

complaints terminated in the 1oct96-30sep07 11-year period with no investigation or private or public discipline. In the last 29 years only three judges –currently 2,180 are subject to the Act- have been impeached and removed. This shows

self-exemption from discipline and coordination to disregard a duty placed by law upon judges. Actually, in the 220 years since the creation of the federal judiciary in 1789, only seven judges have been impeached and removed…on average one every 31 years!

Money provides a motive for discipline self-exemption. Indeed, the chief justice of the Supreme Court and the associate justices are allotted as circuit justices to

the several circuits. With their chief district and circuit judges they review twice a year

reports showing that those judges systematically dismiss complaints against their peers. All of them know too that bankruptcy judges dispose of tens of billions of dollars annually and do so

however they like: In

FY08, 1,043,993 new bankruptcy cases were filed while only 773 were

appealed to the circuit courts. In turn, circuit judges dispose of 75% of appeals by summary

orders, where there is mostly only one operative word, "Affirmed". Those orders have no precedential value, thus

leaving judges free to decide future cases however they want. Such freedom for inconsistent and arbitrary decision-making is further ensured by circuit judges not publishing 83.5% of opinions and orders terminating cases on the merits. So no matter how bankruptcy judges

dispose of money, their rulings are all but assured to stand; otherwise, to be reversed without explanation.

Unaccountable power and lots of money!, the two most insidious corruptors in the hands of discipline self-exempted judges. Risklessness enables and encourages judges to engage in unlawful conduct for profit; coordination allows them to maximize the benefit. A most profitable form of coordinated judicial wrongdoing is a bankruptcy fraud scheme. The case described on page 2, DeLano, now before the Supreme Court (08-8382), provides evidence of such a scheme. Journalists can use it to conduct a pinpointed Watergate-like Follow the money! investigation reminiscent of that led once by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward and likely to reach similar results: The exposure of coordinated or tolerated wrongdoing by judges all the way to the judiciary’s top.

If on average it took 31 years to hold accountable people like B. Madoff, who could dispose of tens of billions of dollars, including your money, and who in addition could exercise power over your property, liberty, and even life however they wanted with no more consequences than the reversal of their decisions, do you think that they would be tempted to treat you and everybody else with arrogant disregard? If all your complaints and everybody else’s ended up in the wastebasket, would you expect everybody to want to know of your efforts to force those people out of their safe haven so as to require them to treat everybody according to law or be liable to all of you? If so, you have a U.S. audience of 303 million persons waiting to know about your efforts to hold those Madoff-like judges accountable for their conduct. Hence, I invite you to read on and then contact me to discuss how I can facilitate the proposed Follow the money! investigation. Read more

DrCordero-journalists.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [3.6 MB]