The Constitution of the United States

Constitution of the United States

United States Senate

Adapted from S.PUB.103-21 (1994), prepared by the Office of the Secretary of the Senate with the assistance of Johnny H. Killian of the Library of Congress, providing the original text of each clause of the Constitution with an accompanying explanation of its meaning and how that meaning has changed over time.

Introduction

Written in 1787, ratified in 1788, and in operation since 1789, the United States Constitution is the world’s longest surviving written charter of government. Its first three words – "We The People" – affirm that the government of the United States exists to serve its citizens. The supremacy of the people through their elected representatives is recognized in Article I, which creates a Congress consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The positioning of Congress at the beginning of the Constitution reaffirms its status as the "First Branch" of the federal government.

The Constitution assigned to Congress responsibility for organizing the executive and judicial branches, raising revenue, declaring war, and making all laws necessary for executing these powers. The president is permitted to veto specific legislative acts, but Congress has the authority to override presidential vetoes by two-thirds majorities of both houses. The Constitution also provides that the Senate advise and consent on key executive and judicial appointments and on the ratification of treaties.

For over two centuries the Constitution has remained in force because its framers successfully separated and balanced governmental powers to safeguard the interests of majority rule and minority rights, of liberty and equality, and of the central and state governments. More a concise statement of national principles than a detailed plan of governmental operation, the Constitution has evolved to meet the changing needs of a modern society profoundly different from the eighteenth-century world in which its creators lived.

This annotated version of the Constitution provides the original text (left-hand column) with commentary about the meaning of the original text and how it has changed since 1789... Read more

Constitution of the United States-US Sen[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [180.3 KB]

constitution-full-text.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [338.6 KB]

- Constitutional Convention Teaching American History.org

- Constitutional Convention Library of Congress

- Constitutional Convention (United States) Wikipedia

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, painting by Howard Chandler Christy, U.S. Senate link

...........................Links - U.S. Constitution................................

U.S. Constitution Annotated U.S. Senate Edition

U.S. Constitution, Analysis and Interpretation, Centennial Edition - Interim Government Printing Office (PDF 2,840 pages) More

- U.S. Constitution The White House

- U.S. Constitution National Archives Transcription here

- Featured Exhibits National Archives

- U.S. Constitution America Bar Association (ABA)

U.S. Constitution full text National Constitution Center (PDF)

Constitution Historical Documents National Constitution Center

U.S. Constitution Annotated Congress.Gov

- U.S. Constitution Annotated Library of Congress

- United States: The Constitution Library of Congress

- Guide to Law Online, U.S. Constitution Library of Congress

- THOMAS The Library of Congress

Primary Documents in American History Library of Congress

- Declaration of Independence

- U.S. Constitution

- The Bill of Rights

- The Federalists Papers

- Continental Congress and Constitutional Convention

- Guide to American Historical Documents Online

- Charters of Freedom National Archives

U.S. Constitution Annotated LLI Cornell Law Non-annotated here

U.S. Constitution Annotated FindLaw

U.S. Constitution Annotated Wikibooks

- U.S. Constitution Wikipedia

- U.S. Constitution Wikipedia Analysis and Interpretation

The Constitution of the United States constitutionus.com

United States Documents of Freedom constitutionus.com

Ginsburg: "I would not look to the U.S. Constitution, if I were drafting a Constitution in the year 2012"

Ginsburg Appears on Egyptian TV, Talks About Constitution

Writing

ABA Journal Law News Now

By Molly McDonough

February 3, 2012

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrapped up a trip to Egypt with an appearance on Egyptian TV,

where in a lengthy interview she discussed the U.S. Constitution and whether it should be a model for Egypt.

While urging that the U.S. Constitution be used as inspiration, Ginsburg said

Egyptians should look to other countries with newer constitutions for guidance, the Huffington Post reports.

"Let me say first, that a constitution, as important as it is, will mean nothing unless the people are yearning for liberty and freedom," Ginsburg said in the 18-minute

interview with Al Hayat TV, which is posted on YouTube. "If the people don’t care, then the best constitution in the world won’t make any

difference."

Ginsburg was in Egypt to meet with judges, legal experts, law faculty and students in Cairo and Alexandria. According to the U.S. Embassy, she was there to "'listen and

learn' with her Egyptian counterparts as they begin Egypt's constitutional transition to democracy," the Huffington Post notes.

On the television program, in a response to a question about drafting a constitution in the modern era, Ginsburg said she would not look to the U.S. Constitution when

drafting in the year 2012 because it excluded women, slaves and Native Americans.

Rather, those writing constitutions should look at all constitution writing since World War II. She pointed specifically to the South African constitution and Canada's

charter of rights and freedoms as good modern examples.

"Why not take advantage of what there is elsewhere in the world? I'm a very strong believer in listening and learning from others," she said.

The Huffington Post reports that no other justice on the current high court has publicly advised another country on the creation of a constitution. Read more

United States Constitution Wikipedia

Declaration of Independence Wikipedia

Constitution of South Africa Wikipedia

Canadian Charter of Rights & Freedoms

European Convention on Human Rights

What Does Benjamin Franklin Have to Do With Obamacare?

In founding the Pennsylvania Hospital, America’s wiliest Founding Father promoted public health by leveraging politics with religion.

The Atlantic, by Svati Kirsten Narula, October 21, 2013

Why Doesn't the Constitution Guarantee the Right to Education? Every country that outperforms the U.S. has a constitutional or statutory commitment to this right. The Atlantic, by Stephen Lurie

10 common misconceptions about the Constitution ABA Journal

Benjamin Franklin was sure that the document had its faults, and just as sure that the framers were fallible. Illustration by RICHARD MCGUIRE

Benjamin Franklin was sure that the document had its faults, and just as sure that the framers were fallible. Illustration by RICHARD MCGUIRE

THE COMMANDMENTS

The New Yorker Magazine

A Critic at Large

January 17, 2011 Issue

By Jill Lepore

The Constitution and

its worshippers

It is written in an elegant, clerical hand, on four sheets of parchment, each two feet wide and a bit more than two feet high, about the size of an eighteenth-century newspaper but finer, and made not from the pulp of plants but from the hide of an animal. Some of the ideas it contains reach across ages and oceans, to antiquity; more were, at the time, newfangled. "We the People," the first three words of the preamble, are giant and Gothic: they slant left, and, because most of the rest of the words slant right, the writing zigzags. It took four months to debate and to draft, including two weeks to polish the prose, neat work done by a committee of style. By Monday, September 17, 1787, it was ready. That afternoon, the Constitution of the United States of America was read out loud in a chamber on the first floor of Pennsylvania’s State House, where the delegates to the Federal Convention had assembled to subscribe their names to a new system of government, "to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common Defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity." Read more

'We the People' Loses Appeal Around the World

‘We the People’ Loses Appeal With People Around the World

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

February 6, 2012

WASHINGTON — The Constitution has seen better days.

Sure, it is the nation’s founding document and sacred text. And it is the oldest written national constitution still in force anywhere in the world. But its influence is

waning.

In 1987, on the Constitution’s bicentennial, Time magazine calculated that

"of the 170 countries that exist today, more than 160 have written charters modeled directly or indirectly on the U.S. version."

A quarter-century later, the picture looks very different. "The U.S. Constitution appears to be losing its appeal as a model for constitutional drafters elsewhere,"

according to a new study by David S. Law of Washington University in St. Louis and Mila Versteeg of the University of

Virginia.

The study, to be published in June in The New York University Law Review, bristles with data. Its authors coded and analyzed the provisions of 729 constitutions adopted

by 188 countries from 1946 to 2006, and they considered 237 variables regarding various rights and ways to enforce them.

"Among the world’s democracies," Professors Law and Versteeg concluded, "constitutional similarity to the United States has clearly gone into free fall. Over the 1960s

and 1970s, democratic constitutions as a whole became more similar to the U.S. Constitution, only to reverse course in the 1980s and 1990s."

"The turn of the twenty-first century, however, saw the beginning of a steep plunge that continues through the most recent years for which we have data, to the point that

the constitutions of the world’s democracies are, on average, less similar to the U.S. Constitution now than they were at the end of World War II."

There are lots of possible reasons. The United States Constitution is terse and old, and it guarantees relatively few rights. The commitment of some members of the

Supreme Court to interpreting the Constitution according to its original meaning in the 18th century may send the signal that it is of little current use to, say, a new African nation. And the

Constitution’s waning influence may be part of a general decline in American power and prestige.

In an interview, Professor Law identified a central reason for the trend: the availability of newer, sexier and more powerful operating systems in the constitutional

marketplace. "Nobody wants to copy Windows 3.1," he said.

In a television interview during a visit to Egypt last week, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the

Supreme Court seemed to agree. "I would not look to the United States Constitution if I were drafting a constitution in the year 2012," she said. She recommended, instead, the South African Constitution, the Canadian Charter of Rights and

Freedoms or the European Convention on Human Rights.

The rights guaranteed by the American Constitution are parsimonious by international standards, and they are frozen in amber. As Sanford Levinson wrote in 2006 in "Our Undemocratic

Constitution," "the U.S. Constitution is the most difficult to amend of any constitution currently existing in the world today." (Yugoslavia used to hold that title, but Yugoslavia did not work

out.) [Monticello.org, tree of liberty question]

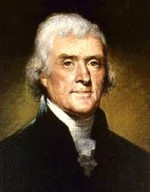

Other nations routinely trade in their constitutions wholesale, replacing them on average every 19 years. By odd coincidence, Thomas Jefferson, in a 1789 letter to

James Madison, once said that every constitution "naturally expires at the end of 19 years" because "the earth belongs always to the living generation." These days, the overlap between the rights

guaranteed by the Constitution and those most popular around the world is spotty.

Americans recognize rights not widely protected, including ones to a speedy and public trial, and are outliers in prohibiting government establishment of religion. But

the Constitution is out of step with the rest of the world in failing to protect, at least in so many words, a right to travel, the presumption of innocence and entitlement to food, education and

health care.

It has its idiosyncrasies. Only 2 percent of the world’s constitutions protect, as the Second Amendment does, a right to bear arms. (Its brothers in arms are Guatemala

and Mexico.)

The Constitution’s waning global stature is consistent with the diminished influence of the

Supreme Court, which "is losing the central role it once had among courts in modern democracies," Aharon Barak, then the president of the Supreme Court of Israel, wrote in The Harvard Law Review in 2002.

Many foreign judges say they have become less likely to cite decisions of the United States Supreme Court, in part because of what they consider its

parochialism.

"America is in danger, I think, of becoming something of a legal backwater," Justice Michael Kirby of the High Court of Australia said in a 2001 interview. He said that he looked instead to India, South Africa and New Zealand.

Mr. Barak, for his part, identified a new constitutional superpower: "Canadian law," he wrote, "serves as a source of inspiration for many countries around the world."

The new study also suggests that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, adopted in 1982, may now be more influential than its American counterpart.

The Canadian Charter is both more expansive and less absolute. It guarantees equal rights for women and disabled people, allows affirmative action and requires that those

arrested be informed of their rights. On the other hand, it balances those rights against "such reasonable limits" as "can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society."

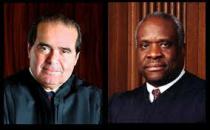

There are, of course, limits to empirical research based on coding and counting, and there is more to a constitution than its words, as Justice Antonin Scalia told the Senate Judiciary Committee in October. "Every banana republic in the world has

a bill of rights," he said.

"The bill of rights of the former evil empire, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was much better than ours," he said, adding: "We guarantee freedom of speech and

of the press. Big deal. They guaranteed freedom of speech, of the press, of street demonstrations and protests, and anyone who is caught trying to suppress criticism of the government will be called

to account. Whoa, that is wonderful stuff!"

"Of course," Justice Scalia continued, "it’s just words on paper, what our framers would have called a ‘parchment guarantee.’ "

‘We the People’ Loses Appeal With People[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [54.1 KB]

Originalism - Back to the Future - September 17, 1787

Originalism

Wikipedia

In the context of United States constitutional interpretation, originalism is a principle of interpretation that tries to discover the original

meaning or intent of the constitution. It is based on the principle that the judiciary is not supposed to create, amend or repeal laws (which is the realm of the

legislative branch) but only to uphold them. The term is a neologism, and the concept is a formalist theory of law and a corollary of textualism.

Today, originalism is popular among political conservatives in the U.S., and

is most prominently associated with Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Robert Bork. However, some liberals, such as Justice Hugo Black and Akhil Amar, have also subscribed to the theory. Read more

JustOneMinute, The NY Times Finds A

Codebreaker

Booknotes interview with Jack Rakove on Original Meanings:

The Originalism Blog Why Originalism Is So Popular

Eric Posner, The New Republic

Legal Theory Lexicon 019: Originalism

The Founder’s Constitution, Kurland & Lerner

Jack Balkin, Bad Originalism

Balkin, Scalia Blowing Smoke Again

Ed Brayton, Balkin on "Bad Originalism"

Second Constitution of the United States?

Second Constitutional Convention

of the United States

Wikipedia

The calling of a Second Constitutional Convention of the United States is a proposal made by some scholars and activists[1] from both the right wing and left wing of the political spectrum[2] for the purpose of making substantive reforms to the United States Federal government by rewriting its Constitution.

Background

Since the initial 1787–88 debate over ratification of the Constitution there have been sporadic calls for the convening of a second convention to modify and correct perceived short comings in the Federal system it established. Article V of the Constitution provides two methods for amending the nation’s frame of government. The first method authorizes Congress, "whenever two-thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary" (a two-thirds of those members present—assuming that a quorum exists at the time that the vote is cast—and not necessarily a two-thirds vote of the entire membership elected and serving in the two houses of Congress), to propose Constitutional amendments. The second method requires Congress, "on the application of the legislatures of two-thirds of the several states" (presently 34), to "call a convention for proposing amendments".[3] Read more

Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (And How We The People Can Correct It)

Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes

Wrong (And How We The People Can Correct It)

Sanford Levinson, Author

The Constitution is one of the most revered documents in American politics. Yet this is a document that regularly places in the White House candidates who did not in fact

get a majority of the popular vote. It gives Wyoming the same number of votes as California, which has seventy times the population of the Cowboy State. And it offers the President the power to

overrule both houses of Congress on legislation he disagrees with on political grounds. Is this a recipe for a republic that reflects the needs and wants of today's Americans? Read more

The New York Times

Levinson argues that too many of our Constitution's provisions promote either unjust or ineffective government. Under the existing blueprint, we can neither rid ourselves of incompetent presidents nor assure continuity of government following catastrophic attacks. Less important, perhaps, but certainly problematic, is the appointment of Supreme Court judges for life. Adding insult to injury, the United States Constitution is the most difficult to amend or update of any constitution currently existing in the world today. Democratic debate leaves few stones unturned, but we tend to take our basic constitutional structures for granted. Levinson boldly challenges the American people to undertake a long overdue public discussion on how they might best reform this most hallowed document and construct a constitution adequate to our democratic values. Read more Sanford Levinson, Wikipedia

____________________________________________

Professor Sanford Levinson talked about his book, Constitutional Faith, on BookTV, in which he argues that the U.S. Constitution is worshipped to a degree that it is unhealthy for our democracy. C-SPAN Book Discussion on Constitutional Faith

- Constitutional Faith, Princeton University Press

- Sanford Levinson, Our Undemocratic Constitution, Duke Law

- C-Span Library, Book Discussion on Constitutional Faith

- How I Lost My Constitutional Faith, Sanford Levinson (PDF)

- Sanford Levinson's Second Thoughts About Constitutional Faith, by Jack M. Balkin, Tulsa Law Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2012, Yale Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 273

- Idolitry and Faith: The Jurisprudence of Sanford Levinson, Jack M. Balkin, 38 TulsaL.Rev.(2003)

How Democratic is the American Constitution? 2nd Ed.

How Democratic is the American Constitution? Second Edition

Robert A. Dahl, Author

Yale political science professor Robert Dahl takes a critical look at our Constitution and why we continue to uphold it, though it is "a document produced more than two centuries ago by a group of fifty-five mortal men, actually signed by only thirty-nine, and

adopted in only thirteen states." As an instrument for truly democratic government, Dahl argues, it fails. With insufficient models to guide them and a distrust of unfettered democracy, the Framers

allowed several "undemocratic elements" in: slavery was accepted and suffrage effectively limited to white men. But Dahl saves his most potent criticism for two provisions that have remained

unchanged: the electoral college and the Senate, both of which tie votes to geography rather than population, thereby skewing political power toward coalitions of smaller states whose interests may

not necessarily coincide with the nation's as a whole. And as the 2000 presidential election illustrated, the electoral college can frustrate the will of the majority. Read more

How Democratic is the American Constitution, selections

A Conversation with Robert A. Dahl

Annual Review of Political Science

Uploaded on May 13, 2011

In this interview, conducted by Margaret Levi, Robert Dahl grounds his motivation for studying democracy not only in his academic encounters but also in his experiences growing up in Alaska, attending public schools there, and working with longshore workers as a boy. He does not want to replicate the utopian visions of classical philosophers. His commitment is to the development of an empirical model of democracy that guides scholars in their efforts to determine the extent of democratization throughout the world as well as in the United States. Interview transcript.

Also see, After the revolution? Authority in a Good Society,

Rev. ed., by Robert A. Dahl, Yale University Press

YouTube video:

- Review of Dahl, On Democracy

- Mark Rom on How Democratic is the American Constitution?

- Noam Chomsky - America is NOT a Democracy

- Republic vs. Democracy - Real Form of the U.S. Government?

- Why America is a Republic, not a Democracy

Death of Robert A. Dahl, age 98, February 8, 2014

- Robert A. Dahl Dies at 98; Yale Scholar Defined Politics and Power, The New York Times, by Douglas Martin

- Robert A. Dahl, Yale professor and political scientist who wrote on Democracy, dies at 98, Washington Times

- Robert Dahl dies at 98; political scientist wrote 'Who Governs?' Los Angeles Times, by Hillel Italie

Law Prof Who Urged Abandoning the Constitution Gets Abusive and Threatening Emails - ABA Law News Now

Law Prof Who Urged Abandoning the Constitution Gets

Abusive and Threatening Emails

ABA Journal Law News Now

By Debra Cassens Weiss

January 3, 2013

The op-ed by Georgetown law professor Louis Michael Seidman was provocative and, apparently, anger-inducing.

Writing in the Sunday New York Times, Seidman said it was

time to abandon the U.S. Constitution and its "archaic, idiosyncratic and downright evil provisions."

"As someone who has taught constitutional law for almost 40 years, I am ashamed it took me so long to see how bizarre all this is." he wrote. Imagine the president or

Congress decides on a course of action. "Suddenly, someone bursts into the room with new information: A group of white propertied men who have been dead for two centuries, knew nothing of our present

situation, acted illegally under existing law and thought it was fine to own slaves might have disagreed with this course of action. Is it even remotely rational that the official should change his

or her mind because of this divination?"

The op-ed, written in advance of Seidman’s new book, On Constitutional Disobedience, brought more than 700 emails in Seidman’s in box, the Wall Street Journal Law Blog (sub. req.) reports. "My email box may never

recover," Seidman told the blog. "I would say a large percentage of them are seriously abusive. Quite a few are anti-Semitic. Some are actual threats." Read more

Louis Michael Seidman, On Constitutional Disobedience 2012, The Scholarly Commons Georgetown Law paper

What would the Framers of the Constitution make of multinational corporations? Nuclear weapons? Gay marriage? They led a preindustrial country, much of it dependent on

slave labor, huddled on the Atlantic seaboard. The Founders saw society as essentially hierarchical, led naturally by landed gentry like themselves. Yet we still obey their commands, two centuries

and one civil war later. According to Louis Michael Seidman, it's time to stop.

In On Constitutional Disobedience, Seidman argues that, in order to bring our basic law up to date, it needs benign neglect. This is a highly controversial assertion. The

doctrine of "original intent" may be found on the far right, but the entire political spectrum--left and right--shares a deep reverence for the Constitution. And yet, Seidman reminds us, disobedience

is the original intent of the Constitution. The Philadelphia convention had gathered to amend the Articles of Confederation, not toss them out and start afresh. The "living Constitution" school tries

to bridge the gap between the framers and ourselves by reinterpreting the text in light of modern society's demands. But this attempt is doomed, Seidman argues. One might stretch "due process of law"

to protect an act of same-sex sodomy, yet a loyal-but-contemporary reading cannot erase the fact that the Constitution allows a candidate who lost the popular election to be seated as president. And

that is only one of the gross violations of popular will enshrined in the document. Seidman systematically addresses and refutes the arguments in favor of Constitutional fealty, proposing instead

that it be treated as inspiration, not a set of commands.

The Constitution is, at its best, a piece of poetry to liberty and self-government. If we treat it as such, the author argues, we will make better progress in achieving

both. Read more

Myths of the American Revolution - by John Ferling

Many American colonists signed up as soldiers for the regular pay. As one recruit put it, "I might as well endeavor to get as much for my skin as I could." (Joe Ciardiello)

Many American colonists signed up as soldiers for the regular pay. As one recruit put it, "I might as well endeavor to get as much for my skin as I could." (Joe Ciardiello)

Myths of the American Revolution

Smithsonian Magazine

By John Ferling

Illustrations by Joe Ciardiello

A noted historian debunks the conventional wisdom about America's War of Independence

We think we know the Revolutionary War. After all, the American Revolution and the war that accompanied it not only determined the nation we would become but also

continue to define who we are. The Declaration of Independence, the Midnight Ride, Valley Forge—the whole glorious chronicle of the colonists’ rebellion against tyranny is in the American DNA. Often

it is the Revolution that is a child’s first encounter with history.

Yet much of what we know is not entirely true. Perhaps more than any defining moment in American history, the War of Independence is swathed in beliefs not borne out by

the facts. Here, in order to form a more perfect understanding, the most significant myths of the Revolutionary War are reassessed. Read more Read more below on this

page.

Myths of the American Revolution.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [119.4 KB]

‘History of the Slave South’ Online Course by Stephanie McCurry For reference only. The course has ended. YouTube video

____________________________________________________

- Who Won the Civil War? New York Times, July 2, 2013

- Book TV: Stephanie McCurry, "Confederate Reckoning"

- Professor Stephanie McCurry, Confederate Reckoning

- But There Was No Peace: The Aftermath of the Civil War

- The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, Public Broadcasting Service

- Michelle Alexander, author of "The New Jim Crow"

Which U.S. Presidents Owned Slaves? (12 white men)

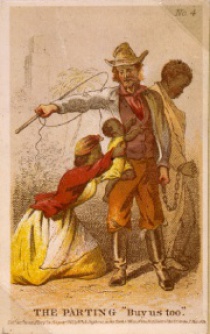

THE PARTING "Buy us too", by Henry Louis Stephens, family is in the process of being separated at a slave auction. (Library of Congress)

THE PARTING "Buy us too", by Henry Louis Stephens, family is in the process of being separated at a slave auction. (Library of Congress)

The Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies

Grand Valley State University

How many of our presidents

owned slaves?

There are two ways of interpreting your question. Either: How many presidents owned slaves at some point in their lives. Or: How many presidents owned slaves while serving as chief executive? Many books get the answers to these questions wrong, and when I speak on the presidents and ask these two questions, audiences invariably low-ball the answer to both.

It comes as a shock to most Americans’ sensibilities that more than one in four U.S. presidents were slaveholder: 12 owned slaves at some point in their lives. Significantly, 8 presidents owned slaves while living in the Executive Mansion. Put another way, for 50 of the first 60 years of the new republic, the president was a slaveholder.

Following is the number of slaves each of the 12 slaveholding presidents owned. (CAPS indicate the president owned slaves while serving as the chief executive):[1]

GEORGE WASHINGTON (between 250-350 slaves)

THOMAS JEFFERSON (about 200)

JAMES MADISON (more than 100)

JAMES MONROE (about 75)

ANDREW JACKSON (fewer than 200)

Martin Van Buren (one)

William Henry Harrison (eleven)

JOHN TYLER (about 70)

JAMES POLK (about 25)

ZACHARY TAYLOR (fewer than 150)

Andrew Johnson (probably eight)

Ulysses S. Grant (probably five)

A number of presidents benefited electorally from "the peculiar institution," especially the four earliest presidents from the then-largest slave state, Virginia. To understand why, one must go back to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, when Southern delegates argued that black slaves should be counted as complete persons, while Northern delegates didn’t want them counted at all since they were not citizens and couldn’t vote. To get over this hurdle and create a unified nation (their highest priority), the delegates decided to negotiate: the North proposed counting black slaves as half a person, and the South countered with three-quarters, so they compromised at three-fifths.

The "three-fifths" clause in the Constitution (Article I, section 2) was all about determining a state’s representation in Congress. That meant southern states collectively gained an advantage that often provided the margin of victory in close elections. In his book Negro President, Garry Wills points out that the slave states always had one-third more seats in Congress than their free population justified. This was decisive in the Election of 1800 in which Thomas Jefferson beat out northern rivals John Adams and Aaron Burr in the House of Representatives

Also, three key Southerners – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison – finagled locating the national capital, Washington, DC, in slave territory. The capital started out in New York City, in a free state, then moved to Philadelphia. But in Philadelphia a slave-owner could only keep a slave for six months before freeing him, unless he was temporarily sent into slave territory, which was inconvenient to the owner. So the founders set aside land around a slave town, Alexandria, Virginia, to serve as the capital of the new nation.

It’s a commonplace that Abraham Lincoln never trafficked in slaves, much less owned them – indeed, he "freed the slaves." But here’s the shocker: Although the slave trade had been abolished in the District of Columbia in 1850, slaves inhabited the capital for another 15 years – till the end of the Civil War. Dwell on that thought: Lincoln fought the Civil War in a slave city – the Great Emancipator inhabited a White House staffed by slaves.

When George Washington died, the Mount Vernon estate’s enslaved population consisted of 318 people. Learn more about George Washington and the enslaved population at Mount Vernon.

George Washington, Slave Catcher - New York Times

George Washington, Slave Catcher

The New York Times

By ERICA ARMSTRONG DUNBAR

FEB. 16, 2015

AMID the car and mattress sales that serve as markers for Presidents’ Day, Black History Month reminds Americans to focus on our common history. In 1926, the African-American historian Carter G. Woodson introduced Negro History Week as a commemoration built around the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Now February serves as a point of collision between presidential celebration and marginalized black history.

While Lincoln’s role in ending slavery is understood to have been more nuanced than his reputation as the great emancipator would suggest, it has taken longer for us to replace stories about cherry trees and false teeth with narratives about George Washington’s slaveholding.

When he was 11 years old, Washington inherited 10 slaves from his father’s estate. He continued to acquire slaves — some through the death of family members and others through direct purchase. Washington’s cache of enslaved people peaked in 1759 when he married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis. His new wife brought more than 80 slaves to the estate at Mount Vernon. On the eve of the American Revolution, nearly 150 souls were counted as part of the property there.

In 1789, Washington became the first president of the United States, a planter president who used and sanctioned black slavery. Washington needed slave labor to maintain his wealth, his lifestyle and his reputation. As he aged, Washington flirted with attempts to extricate himself from the murderous institution — "to get quit of Negroes," as he famously wrote in 1778. But he never did.

During the president’s two terms in office, the Washingtons relocated first to New York and then to Philadelphia. Although slavery had steadily declined in the North, the Washingtons decided that they could not live without it. Once settled in Philadelphia, Washington encountered his first roadblock to slave ownership in the region — Pennsylvania’s Gradual Abolition Act of 1780.

The act began dismantling slavery, eventually releasing people from bondage after their 28th birthdays. Under the law, any slave who entered Pennsylvania with an owner and lived in the state for longer than six months would be set free automatically. This presented a problem for the new president.

Washington developed a canny strategy that would protect his property and allow him to avoid public scrutiny. Every six months, the president’s slaves would travel back to Mount Vernon or would journey with Mrs. Washington outside the boundaries of the state. In essence, the Washingtons reset the clock. The president was secretive when writing to his personal secretary Tobias Lear in 1791: "I request that these Sentiments and this advise may be known to none but yourself & Mrs. Washington."

The president went on to support policies that would protect slave owners who had invested money in black lives. In 1793, Washington signed the first fugitive slave law, which allowed fugitives to be seized in any state, tried and returned to their owners. Anyone who harbored or assisted a fugitive faced a $500 penalty and possible imprisonment.

Washington almost made it through his two terms in office without a major incident involving his slave ownership. On a spring evening in May of 1796, though, Ona Judge, the Washingtons’ 22-year-old slave woman, slipped away from the president’s house in Philadelphia. At 15, she had joined the Washingtons on their tour of Northern living. She was among a small cohort of nine slaves who lived with the president and his family in Philadelphia. Judge was Martha Washington’s first attendant; she took care of Mrs. Washington’s personal needs.

What prompted Judge’s decision to bolt was Martha Washington’s plan to give Judge away as a wedding gift to her granddaughter. Judge fled Philadelphia for Portsmouth, N.H., a city with 360 free black people, and virtually no slaves. Within a few months of her arrival, Judge married Jack Staines, a free black sailor, with whom she had three children. Judge and her offspring were vulnerable to slave catchers. They lived as free people, but legally belonged to Martha Washington.

Washington and his agents pursued Judge for three years, dispatching friends, officials and relatives to find and recapture her. Twelve weeks before his death, Washington was still actively pursuing her, but with the help of close allies, Judge managed to elude his slave-catching grasp.

George Washington died on Dec. 14, 1799. At the time of his death, 318 enslaved people lived at Mount Vernon and fewer than half of them belonged to the former president. Washington’s will called for the emancipation of his slaves following the death of his wife. He completed in death what he had been unwilling to do while living, an act made easier because he had no biological children expecting an inheritance. Martha Washington lived until 1802 and upon her death all of her human property went to her inheritors. She emancipated none of her slaves.

When asked by a reporter if she had regrets about leaving the Washingtons, Judge responded, "No, I am free, and have, I trust, been made a child of God by the means." Ona Judge died on Feb. 25, 1848. She has earned a salute during the month of February.

Correction: February 20, 2015

An Op-Ed article on Monday referred imprecisely to Martha Washington’s handling of George Washington’s slaves after his death in 1799. While she did not emancipate her own slaves, as the essay noted, in 1801 she freed all of his slaves, as he had requested.

____________________

Erica Armstrong Dunbar, an associate professor of black studies and history at the University of Delaware, is the author of "A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City."

George Washington, Slave Catcher - The N[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [47.5 KB]

.......................All men are created equal (?)..........................

The Dark Side of Thomas Jefferson - Smithsonian.com

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account Monticello.Org

Thomas Jefferson fathered six children by his slave Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston Hemings. Read more

Wikipedia

The quotation "All men are created equal" has been called an "immortal declaration", and "perhaps [the] single phrase" of the American Revolutionary period with the greatest "continuing importance".[1][2] Thomas Jefferson first used the phrase in the U.S. Declaration of Independence...The second paragraph of the United States Declaration of Independence starts as follows:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed;[7]

____________________________________________

Hypocrisy of American Slavery

The contradiction between the claim that "all men are created equal" and the existence of American slavery attracted comment when the Declaration of Independence was first published. Before final approval, Congress, having made a few alterations to some of the wording, also deleted nearly a fourth of the draft, including a passage critical of the slave trade. At that time many members of Congress, including Jefferson, owned slaves, which clearly factored into their decision to delete the controversial "anti-slavery" passage.[13] In 1776, abolitionist Thomas Day responding to the hypocrisy in the Declaration wrote, though the first draft stated " All free men are created equal": Wikipedia

If there be an object truly ridiculous in nature, it is an American patriot, signing resolutions of independency with the one hand, and with the other brandishing a whip over his affrighted slaves.[13]

The Monster of Monticello - The Real Thomas Jefferson

The New York Times

By PAUL FINKELMAN

November 30, 2012

Durham, N.C.

THOMAS JEFFERSON is in the news again, nearly 200 years after his death — alongside a high-profile biography by the journalist Jon Meacham comes a damning portrait of the third president by the independent scholar Henry Wiencek.

We are endlessly fascinated with Jefferson, in part because we seem unable to reconcile the rhetoric of liberty in his writing with the reality of his slave owning and his lifetime support for slavery. Time and again, we play down the latter in favor of the former, or write off the paradox as somehow indicative of his complex depths.

Neither Mr. Meacham, who mostly ignores Jefferson’s slave ownership, nor Mr. Wiencek, who sees him as a sort of fallen angel who comes to slavery only after discovering how profitable it could be, seem willing to confront the ugly truth: the third president was a creepy, brutal hypocrite.

Contrary to Mr. Wiencek’s depiction, Jefferson was always deeply committed to slavery, and even more deeply hostile to the welfare of blacks, slave or free. His proslavery views were shaped not only by money and status but also by his deeply racist views, which he tried to justify through pseudoscience.

There is, it is true, a compelling paradox about Jefferson: when he wrote the Declaration of Independence, announcing the "self-evident" truth that all men are "created equal," he owned some 175 slaves. Too often, scholars and readers use those facts as a crutch, to write off Jefferson’s inconvenient views as products of the time and the complexities of the human condition.

But while many of his contemporaries, including George Washington, freed their slaves during and after the revolution — inspired, perhaps, by the words of the Declaration — Jefferson did not. Over the subsequent 50 years, a period of extraordinary public service, Jefferson remained the master of Monticello, and a buyer and seller of human beings.

Rather than encouraging his countrymen to liberate their slaves, he opposed both private manumission and public emancipation. Even at his death, Jefferson failed to fulfill the promise of his rhetoric: his will emancipated only five slaves, all relatives of his mistress Sally Hemings, and condemned nearly 200 others to the auction block. Even Hemings remained a slave, though her children by Jefferson went free.

Nor was Jefferson a particularly kind master. He sometimes punished slaves by selling them away from their families and friends, a retaliation that was incomprehensibly cruel even at the time. A proponent of humane criminal codes for whites, he advocated harsh, almost barbaric, punishments for slaves and free blacks. Known for expansive views of citizenship, he proposed legislation to make emancipated blacks "outlaws" in America, the land of their birth. Opposed to the idea of royal or noble blood, he proposed expelling from Virginia the children of white women and black men.

Jefferson also dodged opportunities to undermine slavery or promote racial equality. As a state legislator he blocked consideration of a law that might have eventually ended slavery in the state.

As president he acquired the Louisiana Territory but did nothing to stop the spread of slavery into that vast "empire of liberty." Jefferson told his neighbor Edward Coles not to emancipate his own slaves, because free blacks were "pests in society" who were "as incapable as children of taking care of themselves." And while he wrote a friend that he sold slaves only as punishment or to unite families, he sold at least 85 humans in a 10-year period to raise cash to buy wine, art and other luxury goods.

Destroying families didn’t bother Jefferson, because he believed blacks lacked basic human emotions. "Their griefs are transient," he wrote, and their love lacked "a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation."

Jefferson claimed he had "never seen an elementary trait of painting or sculpture" or poetry among blacks and argued that blacks’ ability to "reason" was "much inferior" to whites’, while "in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous." He conceded that blacks were brave, but this was because of "a want of fore-thought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present."

A scientist, Jefferson nevertheless speculated that blackness might come "from the color of the blood" and concluded that blacks were "inferior to the whites in the endowments of body and mind."

Jefferson did worry about the future of slavery, but not out of moral qualms. After reading about the slave revolts in Haiti, Jefferson wrote to a friend that "if something is not done and soon done, we shall be the murderers of our own children." But he never said what that "something" should be.

In 1820 Jefferson was shocked by the heated arguments over slavery during the debate over the Missouri Compromise. He believed that by opposing the spread of slavery in the West, the children of the revolution were about to "perpetrate" an "act of suicide on themselves, and of treason against the hopes of the world."

If there was "treason against the hopes of the world," it was perpetrated by the founding generation, which failed to place the nation on the road to liberty for all. No one bore a greater responsibility for that failure than the master of Monticello.

______________

Paul Finkelman, a visiting professor in legal history at Duke Law School, is a professor at Albany Law School and the author of "Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson."

A version of this op-ed appears in print on December 1, 2012, on page A25 of the New York edition with the headline: The Monster of Monticello.

The Real Thomas Jefferson - The New York[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [42.0 KB]

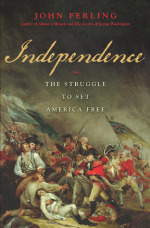

Independence: The Struggle to Set America Free

Independence: The Struggle to Set America Free John Ferling, Author

John Ferling Author's Web Site

No event in American history was more pivotal-or more furiously contested-than Congress's decision to declare independence in July 1776. Even months after American blood

had been shed at Lexington and Concord, many colonists remained loyal to Britain. John Adams, a leader of the revolutionary effort, said bringing the fractious colonies together was like getting

"thirteen clocks to strike at once."

Other books have been written about the Declaration, but no author has traced the political journey from protest to Revolution with the narrative scope and flair of John

Ferling. Independence takes readers from the cobblestones of Philadelphia into the halls of Parliament, where many sympathized with the Americans and furious debate erupted over how to deal with the

rebellion. Independence is not only the story of how freedom was won, but how an empire was lost.

At this remarkable moment in history, high-stakes politics was intertwined with a profound debate about democracy, governance, and justice. John Ferling, drawing on a

lifetime of scholarship, brings this passionate struggle to life as no other historian could. Independence will be hailed as the finest work yet from the author Michael Beschloss calls "a national

resource."

"This is how it really happened. In unequivocal prose, John Ferling captures the combined bluster and outrage on both sides of the Atlantic. He exposes the quirks, while

exploring the vision, of the opinionated, opportunistic delegates who were present in Philadelphia in 1776; he shows us just how they rhetorically overcame the "mystique of invincibility" that

attached to the British military, before launching America, in the words of one delegate, "on a most Tempestuous Sea." Independence is rich in personality, and Ferling unsurpassed as an authority.

This is no ordinary history."—Andrew Burstein, author of Jefferson’s Secrets, and coauthor of Madison and Jefferson

"John Ferling has established himself as one of the leading chroniclers of the American Revolution, but Independence goes beyond anything he has written before. Instead

of recycling the familiar story of the Revolution, he has given us an enlightening and exciting book that proves that history has no guarantees or foreordained outcomes. Expertly blending

biographical vignettes with fast-paced narrative and sure-footed interpretation, Ferling captures the mystery of historical contingency in exploring the period between the Boston Tea Party in 1773

and the declaration of American independence in 1776. Not even the founding fathers knew what the future would bring; Ferling performs a national public service in reminding us of this basic fact,

and demonstrating it with elegance and style."—R. B. Bernstein, distinguished adjunct professor of law, New York Law School, and author of The Founding Fathers Reconsidered and Thomas

Jefferson. Read more

- Review by Chuck Leddy, Boston.com

- Review by Publishers Weekly

- Almost a Miracle: America's War of Independence

- Independence by John Ferling

- Link American Revolutionary War, Wikipedia

C-Span: In Depth With John Ferling, July 5, 2009, three hour video interview from George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate, Museum, & Gardens (Susan Swain, host)

................American Revolutionary War, Wikipedia.............

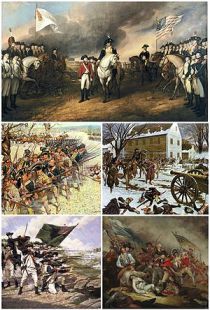

Clockwise from top left: Surrender of Lord Cornwallis after the Siege of Yorktown, Battle of Trenton, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Battle of Long Island, Battle of Guilford Court House

Clockwise from top left: Surrender of Lord Cornwallis after the Siege of Yorktown, Battle of Trenton, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Battle of Long Island, Battle of Guilford Court House

American Revolutionary War

Wikipedia

The American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the American War of Independence,[N 1] or simply the Revolutionary War in the United States, was the armed conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen of its former North American colonies, which had declared themselves the independent United States of America.[N 2][19] Early fighting took place primarily on the North American continent. In 1778, France, eager for revenge after its defeat in the Seven Years' War, signed an alliance with the new nation. The conflict then escalated into a world war with Britain combating France, Spain, and the Netherlands. Contemporaneous fighting also broke out in India between the British East India Company and the French allied Kingdom of Mysore.

The war had its origins in the resistance of many Americans to taxes imposed by the British parliament, which they claimed were unconstitutional. Patriot protests escalated into boycotts and the destruction of a shipment of tea at the Boston Tea Party. The British government punished Massachusetts by closing the port of Boston and taking away self-government. The Patriots responded by setting up a shadow government that took control of the province outside of Boston. Twelve other colonies supported Massachusetts, formed a Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance, and set up committees and conventions which effectively seized power from the royal governments. In April 1775 fighting broke out between Massachusetts militia units and British regulars at Lexington and Concord. The Continental Congress appointed General George Washington to take charge of militia units besieging British forces in Boston, forcing them to evacuate the city in March 1776. Congress supervised the war, giving Washington command of the new Continental Army; he also coordinated state militia units.

In July 1776, the Continental Congress formally declared independence.[20] The British were meanwhile mustering forces to suppress the revolt. Sir William Howe outmaneuvered and defeated Washington, capturing New York City and New Jersey. Washington was able to capture a Hessian detachment at Trenton and drive the British out of most of New Jersey. In 1777 Howe's army launched a campaign against the national capital at Philadelphia, failing to aid Burgoyne's separate invasion force from Canada. Burgoyne's army was trapped and surrendered after the Battles of Saratoga in October 1777. This American victory encouraged France to enter the war in 1778, followed by its ally Spain in 1779.

In 1778, having failed in the northern states, the British shifted strategy toward the southern colonies, where they planned to enlist many Loyalist regiments. British forces had initial success in bringing Georgia and South Carolina under control in 1779 and 1780, but the Loyalist surge was far weaker than expected. In 1781 British forces moved through Virginia, but their escape was blocked by a French naval victory. Washington took control of a Franco-American siege at Yorktown and captured the entire British force of over 7,000 men. The defeat at Yorktown finally turned the British Parliament against the war, and in early 1782 voted to end offensive operations in North America. The war against France and Spain continued however, with the British defending Gibraltar against a long running Franco-Spanish siege, while the British navy scored key victories, especially the Battle of the Saintes in 1782. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the war and recognized the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded roughly by what is now Canada to the north, Florida to the south, and the Mississippi River to the west. France gained its revenge and little else except a heavy national debt, while Spain acquired Britain's Florida colonies.[21][22] Read more

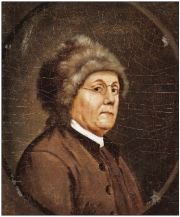

..............Benjamin Franklin "The First American"...............

Wikipedia

Ben Franklin, "The First American"

Ben Franklin, in his fur hat, charmed the French with what they saw as rustic new world genius.

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6,

1705][1] – April 17, 1790) was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A renowned polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, freemason, postmaster, scientist, inventor, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of

physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. He invented the lightning rod, bifocals, the Franklin stove, among other inventions.[2] He

facilitated many civic organizations, including Philadelphia's fire department and a university.[3].

Franklin earned the title of "The First American" for his early and indefatigable campaigning for colonial unity, first as an author and spokesman in London for several colonies. As the first United States Ambassador to France, he exemplified the emerging American nation.[4] Read more

The Franklin Institute, Philadelphia

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN is the story of one of the most remarkable and multi-talented human beings the world has ever known. An epic yarn spanning most of the 18th century, the three-part series follows Franklin's career from humble beginnings in Boston to international superstardom: first as a scientist and revolutionary, and then as a founding father and America's first diplomat to France. Link to Ben Franklin PBS Documentary YouTube video

What Does Benjamin Franklin Have to Do With Obamacare?

In founding the Pennsylvania Hospital, America’s wiliest Founding Father promoted public health by leveraging politics with religion.

The Atlantic, by Svati Kirsten Narula, October 21, 2013

Why Doesn't the Constitution Guarantee the Right to Education? Every country that outperforms the U.S. has a constitutional or statutory commitment to this right. The Atlantic, by Stephen Lurie

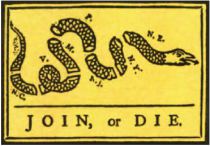

"Join, or Die" by Benjamin Franklin was recycled to encourage the former colonies to unite against British rule

"Join, or Die" by Benjamin Franklin was recycled to encourage the former colonies to unite against British rule

Join, or Die

Wikipedia

"Join, or Die" is a well-known political cartoon, created by Benjamin Franklin and first published in his Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754.[1] The original publication by the Gazette is the earliest known pictorial representation of colonial union produced by a British colonist in America.[2] It is a woodcut showing a snake cut into eighths, with each segment labeled with the initials of one of the thirteen American colonies or region. New England was represented as one segment, rather than the four colonies it was at that time. In addition, Delaware (then a part of Pennsylvania) and Georgia were omitted completely. Thus, it has eight segments of snake rather than the traditional 13 colonies.[3] The two northernmost British American colonies at the time, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, were not represented, nor were any British Caribbean possessions. The cartoon appeared along with Franklin's editorial about the "disunited state" of the colonies, and helped make his point about the importance of colonial unity. This cartoon was used in the French and Indian War to symbolize that the colonies needed to join together with Great Britain to defeat the French and Indians. It became a symbol of colonial freedom during the American Revolutionary War. Read more

Boston Tea Party December 16, 1773

From Eyewitness to History.com

In Boston, the arrival of three tea ships ignited a furious reaction. The crisis came to a head on December 16, 1773 when as many as 7,000 agitated locals milled about the wharf where the ships were docked. A mass meeting at the Old South Meeting House that morning resolved that the tea ships should leave the harbor without payment of any duty. A committee was selected to take this message to the Customs House to force release of the ships out of the harbor. The Collector of Customs refused to allow the ships to leave without payment of the duty. Stalemate. The committee reported back to the mass meeting and a howl erupted from the meeting hall. It was now early evening and a group of about 200 men, some disguised as Indians, assembled on a near-by hill. Whopping war chants, the crowd marched two-by-two to the wharf, descended upon the three ships and dumped their offending cargos of tea into the harbor waters. Read more Read more on Wikipedia

Give me liberty or give me death, March 23, 1775

Patrick Henry - "Give me liberty or give me death"

"Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, Give me Liberty, or give me Death!

One of the most influential, radical advocates of the American Revolution and republicanism, especially in his denunciations of corruption in government officials and his

defense of historic rights. Read more

The Shot Heard 'Round The World April 19, 1775

"By the rude bridge that arched

the flood, Their flag to April's

breeze unfurled; Here once

the embattled farmers stood, And

fired the shot heard 'round the world."

Ralph Waldo Emerson's "Concord Hymn" (1837). The stanza is inscribed at the base of the Minute Man statue by Daniel Chester French, located in Concord,

Massachusetts.

Battle at Lexington Green, April 19, 1775

The Start of the American Revolution and the "shot heard round the world." Eyewitness to

History.com

Massachusetts Colony was a hotbed of sedition in the spring of 1775. Preparations for conflict with the Royal authority had been underway throughout the winter with the production of arms and munitions, the training of militia (including the minutemen), and the organization of defenses. In April, General Thomas Gage, military governor of Massachusetts decided to counter these moves by sending a force out of Boston to confiscate weapons stored in the village of Concord and capture patriot leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock reported to be staying in the village of Lexington. Read more

Ben Franklin Joins the American Revolution 1775

Benjamin Franklin Joins the Revolution

Smithsonian.com

by Walter Isaacson

August 01, 2003

Returning to Philadelphia from England in 1775, the "wisest American" kept his political leanings to himself. But not for long.

Just as his son William had helped him with his famed kite-flying experiment, now William’s son, Temple, a lanky and fun-loving 15-year-old, lent a hand as he lowered a

homemade thermometer into the ocean. Three or four times a day, they would take the water’s temperature and record it on a chart. Benjamin Franklin had learned from his Nantucket cousin, a whaling

captain named Timothy Folger, about the course of the warm Gulf Stream. Now, during the latter half of his six-week voyage home from London, Franklin, after writing a detailed account of his futile

negotiations, turned his attention to studying the current. The maps he published and the temperature measurements he made are now included on NASA’s Web site, which notes how remarkably similar they

are to ones based on infrared data gathered by modern satellites.

The voyage was notably calm, but in America the longbrewing storm had begun. On the night of April 18, 1775, while Franklin was in mid-ocean, a contingent of British

redcoats headed north from Boston to arrest the tea party planners Samuel Adams and John Hancock and capture the munitions stockpiled by their supporters. Paul Revere spread the alarm, as did others

less famously. When the redcoats reached Lexington, 70 American minutemen were there to meet them. "Disperse, ye rebels," a British major ordered. At first they did. Then a shot was fired. In the

ensuing skirmish, eight Americans were killed. The victorious redcoats marched on to Concord, where, as Ralph Waldo Emerson would put it, "the embattled farmers stood, and fired the shot heard round

the world." On the redcoats’ daylong retreat back to Boston, more than 250 of them were killed or wounded by American militiamen. Read more

Declaration of Independence July 4, 1776

The United States Declaration of Independence is a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain were now independent states, and thus no longer a part of the British Empire. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration is a formal explanation of why Congress had voted on July 2 to declare independence from Great Britain, more than a year after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. The birthday of the United States of America—Independence Day—is celebrated on July 4, the day the wording of the Declaration was approved by Congress. Read more

"I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country" September 22, 1776

Nathan Hale, American hero

"I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country"

Nathan Hale was a soldier for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Widely considered America's first spy,

he volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission, but was captured by the British. He is best remembered for his speech before being hanged following the Battle of Long Island, in which he said,

"I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country." Read more

Washington Crossing the Delaware, December 25, 1776

Washington's Crossing of the Delaware River, occurring on

December 25, 1776 during the American Revolutionary War, was the first move in a planned surprise attack organized by George Washington against the Hessian forces in Trenton, New Jersey.

Planned in some secrecy, Washington led a column of Continental Army troops across the icy Delaware River in a logistically challenging and potentially dangerous operation. Other planned crossings in

support of the operation were either called off or ineffective, but this did not prevent Washington from successfully surprising and defeating the troops of Johann Rall quartered in Trenton. The army

crossed the river back to Pennsylvania, this time burdened by prisoners and military stores taken as a result of the battle. Read more

About the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, December 25, 1776, by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, c. 1851

British General John Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga

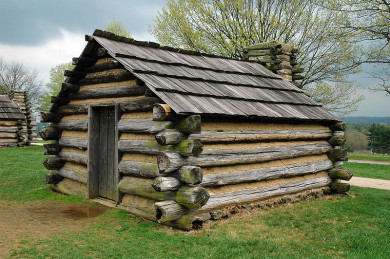

Valley Forge December 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778

Painting "The March to Valley Forge" by William Trego.

Valley Forge Wikipedia

Valley Forge, 40 km (25 mi) west of Philadelphia, was the campground of 11,000 troops of George Washington's Continental Army from Dec. 19, 1777, to June 19, 1778. Because of the suffering endured there by the hungry, poorly clothed, and badly housed troops, 2,500 of whom died during the harsh winter, Valley Forge came to symbolize the heroism of the American revolutionaries. Despite adverse circumstances, Baron Friedrich von Steuben drilled the soldiers regularly and improved their discipline. Today the historic landmarks and monuments are preserved within Valley Forge National Historical Park (established 1976). Read more

British General Cornwallis surrendered at the Siege of Yorktown

- The Washington Family, ArtBabble.org

- The Washington Family, National Gallery of Art

- The Washington Family, PBS Africans in America

- The Washington Family, Martha Washington

- The Washington Family, Humanities Texas

- The Washington Family, Reynolda House Museum

- The Washington Family, Joseph Manca, JSTORE

- The Washington Family, Wikipedia

- George Washington, Biography, Mount Vernon.org

- George Washington, Wikipedia

- George Washington, Google

- George Washington's Farewell Address, U.S. Senate

- George Washington's Farewell Address, National Archives

- George Washington's Farewell Address, Yale Law School

- George Washington's Farewell Address, Wikipedia

- United States non-interventionism, Wikipedia

- The American Doctrine of Nonintervention

George Washington’s Farewell Address is often cited as laying the foundation for a tradition of American non-interventionism:

"The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities."

-- George Washington, Farewell Address

September 19, 1796