Was the Civil War About Slavery?

By Colonel Ty Seidule

Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at West Point

What caused the Civil War? Did the North care about abolishing slavery? Did the South secede because of slavery? Or was it about something else entirely...perhaps states'

rights? Colonel Ty Seidule, Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at West Point, settles the debate.

For more information on the Civil War, check out The West Point History of the Civil War, an interactive e-book that brings the Civil War to life in a way that's never been done. Transcript

seidule-civil_war-transcript.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [224.9 KB]

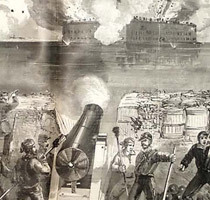

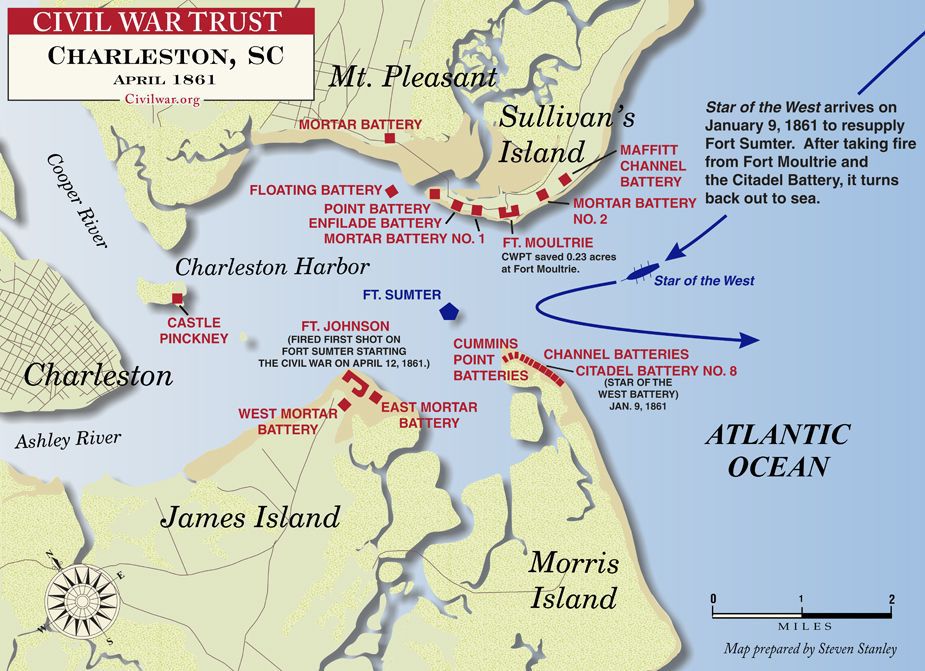

Confederate attack on Fort Sumter - Civil War begins!

On Thursday, April 11, 1861, Confederate Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard dispatched aides to Maj. Anderson to demand the fort’s surrender. Anderson refused. The next morning, at 4:30 a.m., Confederate batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter for 34 more hours.

Photo Journal by

William Bechmann

USMC Sergeant Major

On April 12, 1861, the bloodiest four years in American history begin when Confederate shore batteries under General P.G.T. Beauregard open fire on Union-held Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Bay. During the next 34 hours, 50 Confederate guns and mortars launched more than 4,000 rounds at the poorly supplied fort. On April 13, U.S. Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort. Two days later, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 75,000 volunteer soldiers to quell the Southern "insurrection." Read more

___________________________________________________

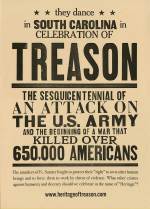

Treason Against The United States of America

_____________________________________________

Treason Against the United States

The New York Times

Published: January 25, 1861

By Section 110 of Article III. of the Constitution of the United States, it is declared that:

"Treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open Court. The Congress shall have power to declare the punishment of treason."

In 1790, the Congress of the United States enacted that:

"If any person or persons, owing allegiance to the United States of America, shall levy war against them, or shall adhere to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States, or elsewhere, and shall be thereof convicted on confession in open Court, or on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act of the treason whereof he or they shall stand indicted, such person or persons shall be adjudged guilty of treason against the United States, and SHALL SUFFER DEATH; and that if any person or persons, having knowledge of the commission of any of the treasons aforesaid, shall conceal, and not, as soon as may be, disclose and make known the same to the President of the United States, or some one of the Judges thereof, or to the President or Governor of a particular State, or some one of the Judges or Justices thereof, such person or persons, on conviction, shall be adjudged guilty of misprision of treason, and shall be imprisoned not exceeding seven years, and fined not exceeding one thousand dollars." Read more

__________________________________________________

U.S. Constitution, Article III, Section 3 Treason

Legal Information Institute, CRS Annotated Constitution

Section 3. Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open court.

18 U.S. Code Chapter 115 - TREASON, SEDITION, AND SUBVERSIVE ACTIVITIES Legal Information Institute, Cornell U Law School

18 U.S.Code § 2381 - Treason

Whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason and shall suffer death, or shall be imprisoned not less than five years and fined under this title but not less than $10,000; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

______________________________________________________________

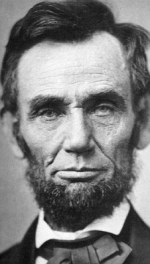

President Abraham Lincoln As Commander In Chief

The Lehrman Institute Featured Book

James M. McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (Penguin Press HC, 2008)

"...The nation’s president did not have the military education or experience of his Confederate counterpart, Jefferson Davis. But Lincoln was a conscientious scholar – and he became a student of military tactics and eventually a better master of military strategy than his generals or Davis. “The President is himself a man of great aptitude for military studies,” wrote aide John Hay early in the war.2 Historian T. Harry Williams said President Lincoln was “a great natural strategist, a better one than any of his generals. He was in actuality as well as in title the commander in chief who, by his larger strategy, did more than Grant or any other general to win the war for the Union...." Read more

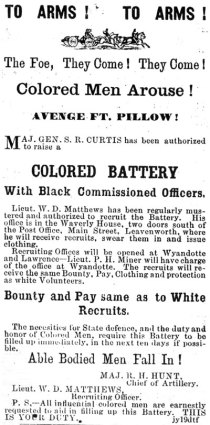

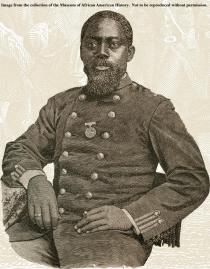

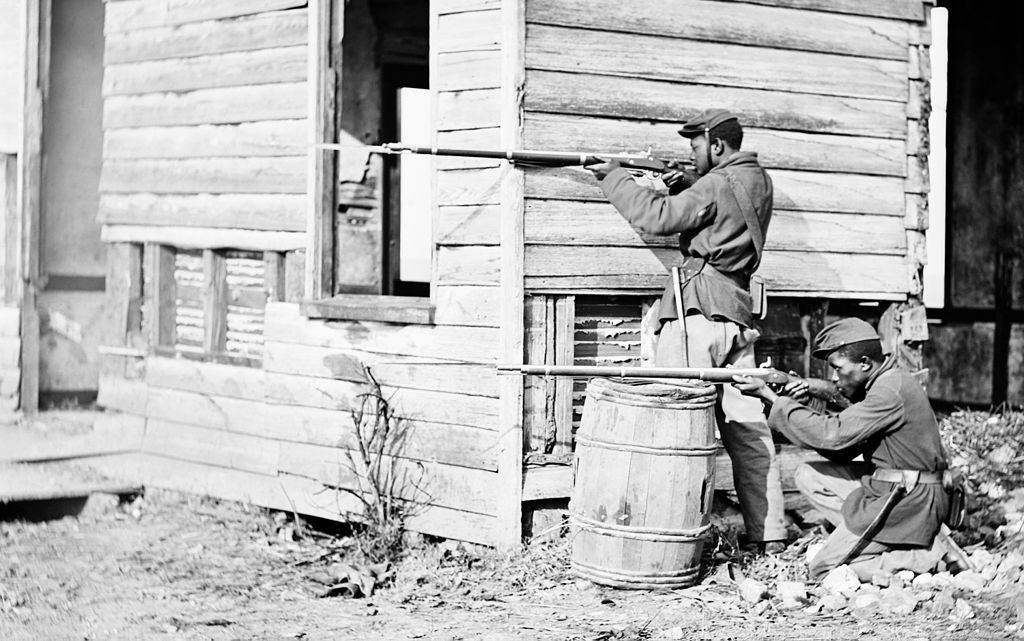

The 4th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment - Former Slaves

The 4th United States Colored Infantry Regiment was an African American unit of the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom

Black Soldiers

Historian John Hope Franklin (Wikipedia) wrote that at the beginning of the Civil War : "When Negroes rushed to offer their services to the Union, they were rejected. In almost every town of any size there were large numbers of Negroes who sought service in the Union army; failing to be enlisted they bided their time and did whatever they could to assist."1

Historian Susan-Mary Grant wrote "that when hostilities commenced between North and South in 1861 blacks throughout the North, and some in the South too, sought to enlist. However, free blacks in the North who sought to respond to Abraham Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers found that their services were not required by a North in which slavery had been abolished but racist assumptions still prevailed. Instead they were told quite firmly that the war was a 'white man's fight' and offered no role for them. The notable northern black leader, Frederick Douglass, himself an escaped slave, summed the matter up succinctly:"2

Colored men were good enough to fight under Washington. They are not good enough to fight under McClellan. They were good enough to fight under Andrew Jackson. They are not good enough to fight under Gen. Halleck. They were good enough to help win American Independence but they are not good enough to help preserve that independence against treason and rebellion. They were good enough to defend New Orleans but not good enough to defend our poor beleaguered Capital.3

The move to reverse that military deficiency came slowly – moving into full gear only in the spring of 1863.

Historian Benjamin P. Thomas wrote: "Although Lincoln announced the proposed use of colored troops in the Emancipation Proclamation, he had not come easily to that decision. The act of July 17, 1862 gave him complete discretion in the employment of Negroes for any purpose whatsoever, but he had shrunk from using black men to kill white men. To deprive the South of the services of her slaves was a legitimate and necessary war measure. To use colored men as teamsters and laborers in the Union army would release white men for combat. But to put weapons in the hands of black men, some of whom might become frenzied with the flush of new-found freedom, was a matter of most serious consequence."4 Read more

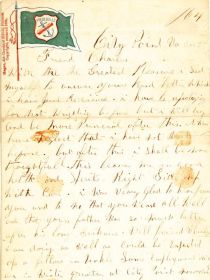

Black soldier's letter offers rare view of Civil War

USA Today, By Diana Penner

The Indianapolis Star

March 5, 2013

Missive detailing soldier's thoughts on war, racial equality could fetch up to $8,000 at New York auction.

INDIANAPOLIS -- John Carter, a prosperous African-American grocery store owner in Madison, Ind., before and after the Civil War, was active on the Underground Railroad, secretly ferrying slaves from the South to freedom in the North.

For more than a century, a letter written Dec. 3, 1864, by his son, Morgan W. Carter, detailing a bloody Civil War battle and outlining a vision of free blacks, also was underground.

The letter, long in the hands of private collectors and out of public view, is set to go up for auction March 21 at Swann Galleries in New York....

...Writing about one battle, Carter described "the long to be remembered field of bloodshed and slaughter. ... There many a poor fell(ow) lost thear life for thear country and thear people." Read the full transcript of Carter's letter here or below in PDF.

Letter of Sgt. Morgan W. Carter, Company[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [234.6 KB]

Wikipedia

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed of African-American (colored) soldiers; they were first recruited during the American Civil War, and by the end of that war in April, 1865, the 175 USCT regiments constituted about one-tenth the manpower of the Union Army.

In the decades that followed the USCT soldiers fought in the Indian Wars in the American West, where they became known as the Buffalo Soldiers; they received the nickname from Native Americans who compared their hair to the fur of bison. Read more

- Black Civil War Soldiers - American Civil War - HISTORY.com

- Black Soldiers in the Civil War - National Archives

- African-American Civil War Soldiers - Library of Congress

- Importance of African-American Soldiers Civil War History

- Fighting for Freedom, Black Union Soldiers of the Civil War

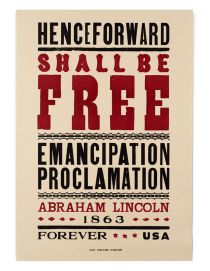

The Emancipation Proclamation - January 1, 1863

Black Past.Org

National Archives

Emancipation Proclamation

State Library of North Carolina

Emancipation Proclamation

Wikipedia

The Emancipation Proclamation consists of two executive orders issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War. The first one, issued September 22, 1862, declared the freedom of all slaves in any state of the Confederate States of America that did not return to Union control by January 1, 1863. The second order, issued January 1, 1863, named ten specific states where it would apply. Lincoln issued the Executive Order by his authority as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy" under Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution.

______________________________________________

"... I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons."

Abraham Lincoln, The Emancipation Proclamation. Jan. 1, 1863

______________________________________________

The proclamation did not name the slave-holding border states of Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, or Delaware, which had never declared a secession, and so it did not free any slaves there. The state of Tennessee had already mostly returned to Union control, so it also was not named and was exempted. Virginia was named, but exemptions were specified for the 48 counties that were in the process of forming West Virginia, as well as seven other named counties and two cities. Also specifically exempted were New Orleans and thirteen named parishes of Louisiana, all of which were also already mostly under Federal control at the time of the Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation was criticized at the time for freeing only the slaves over which the Union had no power. Although most slaves were not freed immediately, the Proclamation did free thousands of slaves the day it went into effect in parts of nine of the ten states to which it applied (Texas being the exception). In every Confederate state (except Tennessee and Texas), the Proclamation went into immediate effect in Union-occupied areas and at least 20,000 slaves were freed at once on January 1, 1863. Read more

The New York Times

By LOUIS P. MASUR

December 31, 2012

THE Emancipation Proclamation, signed 150 years ago today, was a revolutionary achievement, and widely recognized as such at the time. Abraham Lincoln himself declared,

"If my name goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it."

On New Year’s Eve, 1862, "watch-night" services in auditoriums, churches, camps and cabins united thousands, free as well as enslaved, who sang, prayed and counted down

to midnight. At a gathering of runaway slaves in Washington, a man named Thornton wept: "Tomorrow my child is to be sold never more."

The Day of Jubilee, as Jan. 1, 1863 was called, arrived at last and celebrations of deliverance and freedom commenced. "We are all liberated by this proclamation,"

Frederick Douglass observed. "The white man is liberated, the black man is liberated." The Fourth of July "was great," he proclaimed, "but the First of January, when we consider it in all its

relations and bearings, even greater." more

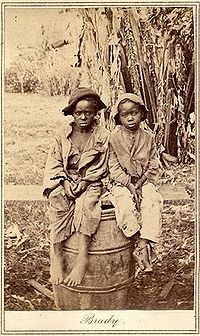

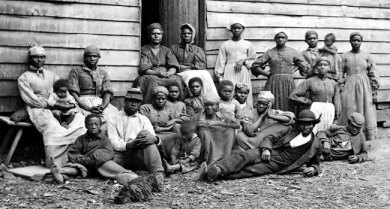

African-Americans who escaped slavery on a plantation, May, 1862 Cumberland Landing, Virginia.

- After the Sale: Slaves Going South from Richmond

- Virginia Memory: Interstate Slave Trade

Ten frequently asked questions

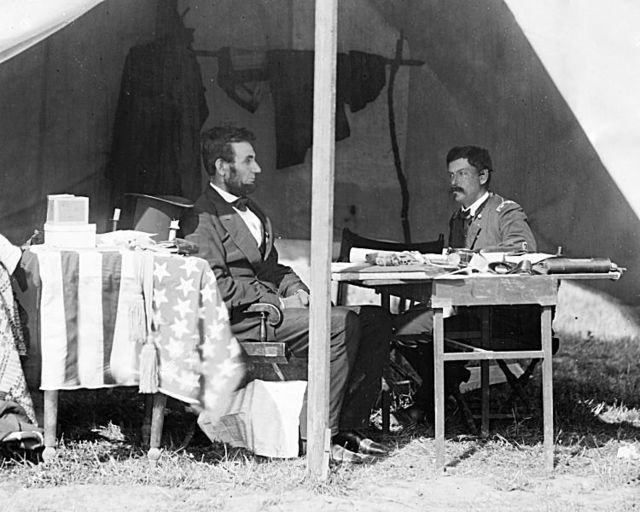

President Abraham Lincoln October 3, 1862 on the Battlefield of Antietam with Allan Pinkerton (Left) and General McClernand (Right). The next day Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation appeared for the first time on the pages of Harper's Weekly, the most widely distributed newspaper of the day.

The Battle of Antietam September 17, 1862 was the bloodiest day in American military history. Antietam was a defining moment in American History. In the fall of 1862, Lincoln was desperate for a victory in the Civil War. Up to that time, the South had achieved victory after victory. Bull Run, Wilson's Creek, and Shiloh had all been convincing victories for the South. Lincoln realized that if the North did not achieve a victory soon, the survival of the Union would be in doubt. This led Lincoln to look to God and make an offer . . . Lincoln prayed that if God would grant him victory on the battlefield, he would free the slaves.

Slavery had haunted Lincoln for some time. He fully realized the cruelty and brutality of this corrupt institution. Shortly thereafter Linclon received news of McClellan's success at Antietam. McClellan was able to drive Lee out of Maryland, and back into Virginia. On September 22, 1862 Abraham Lincoln honored the promise he made to God, and issued the Emancipation Proclamation. (Wiki)

Credit: Defining Moments/Old Pictures, Library of Congress

- Emancipation Proclamation - PBS

- Emancipation Proclamation - Library of Congress

- Lincoln Papers: Emancipation Proclamation: Introduction

- Liberty Is A Slow Fruit, The American Scholar

- Featured Document: The Emancipation Proclamation

- The Emancipation of Abe Lincoln NYT by Eric Foner

-

Emancipation Proclamation Black Past.Org

-

Emancipation Proclamation National Park Service

-

Emancipation Proclamation National Archives

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth...a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal... Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation... can... endure...we here highly resolve...that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." - Abraham Lincoln

Below is the text from the Hay draft, or the so-called second draft of the speech that was written either the morning of the speech, or upon Lincoln’s return to Washington. Hay was the personal secretary of Lincoln, and he was given this copy by Lincoln:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battle field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

The Gettysburg Address, Cornell Univesity

Gettysburg Address, 5 known manuscripts Wikipedia

Retraction for our 1863 editorial calling Gettysburg Address 'silly remarks' The Patriot News - Editorial

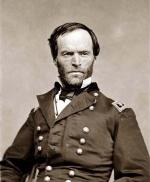

William Tecumseh Sherman

Wikipedia

William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–65), for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched earth" policies that he implemented in conducting total war against the Confederate States. Read more

_____________________________________________

Sherman’s Demons, NYT by Michael Fellman, November 9, 2011

Madness, Genius, & Sherman’s Ruthless March, WIRED Magazine

Why General Sherman was a war-hater, by Nassir Ghaemi M.D.

Teaching American History.org

William T. Sherman letter to James M. Calhoun, et al

From Headquarters Military Division of the Mississippi, in the Field, Atlanta, Georgia, September 12, 1864

"You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now, it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal, war. The United States does and must assert its authority, wherever it once had power; for, if it relaxes one bit to pressure, it is gone, and I believe that such is the national feeling. This feeling assumes various shapes, but always comes back to that of Union. Once admit the Union, once more acknowledge the authority of the national Government, and, instead of devoting your houses and streets and roads to the dread uses of war, I and this army become at once your protectors and supporters, shielding you from danger, let it come from what quarter it may. I know that a few individuals cannot resist a torrent of error and passion, such as swept the South into rebellion, but you can point out, so that we may know those who desire a government, and those who insist on war and its desolation." Read more

Forty Acres and a Mule:

Special Field Order No. 15

William Tecumseh Sherman

Headquarters Military Division of the Mississippi,

In the Field, Savannah, Georgia January 16, 1865

"1. The islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice-fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. John’s River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States." Read more

_________________________________________________

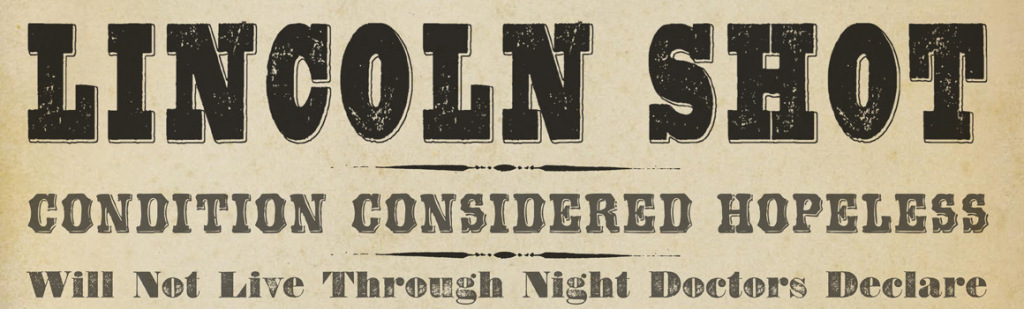

Assassination Conspiracy To Revive The Confederate Cause

_________________________________________________

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

Wikipedia

United States President Abraham Lincoln was shot on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, while attending the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre as the American Civil War was drawing to a close.[1] The assassination occurred five days after the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, surrendered to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army of the Potomac.

Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated.[2] An unsuccessful attempt had been made on Andrew Jackson 30 years before in 1835, and Lincoln had himself been the subject of an earlier assassination attempt by an unknown assailant in August 1864. The assassination of Lincoln was planned and carried out by the well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, as part of a larger conspiracy in a bid to revive the Confederate cause.

Booth's co-conspirators were Lewis Powell and David Herold, who were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward, and George Atzerodt who was tasked to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. By simultaneously eliminating the top three people in the administration, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to sever the continuity of the United States government.

Lincoln was shot while watching the play Our American Cousin with his wife Mary Todd Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.. He died early the next morning. The rest of the conspirators' plot failed; Powell only managed to wound Seward, while Atzerodt, Johnson's would-be assassin, lost his nerve and fled. The funeral and burial of Abraham Lincoln was a period of national mourning.

In late 1860, Booth had been initiated in the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle in Baltimore.[3] Read more

..................Conclusion of the American Civil War...............

Conclusion of the American Civil War Wikipedia

This is a timeline of the conclusion of the American Civil War which includes important battles, skirmishes, raids and other events of 1865. These led to additional Confederate surrenders, key Confederate captures, and disbandments of Confederate military units that occurred after Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865.[1]

The fighting of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War between Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Potomac and Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was reported considerably more often in the newspapers than the battles of the Western Theater. Reporting of the Eastern Theater skirmishes largely dominated the newspapers as the Appomattox Campaign developed.[2]

Lee’s army fought a series of battles in the Appomattox Campaign against Grant that ultimately stretched thin his lines of defense. Lee's extended lines were mostly on small sections of thirty miles of strongholds around Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. His troops ultimately became exhausted defending this line because they were too thinned out. Grant then took advantage of the situation and launched attacks on this thirty mile long poorly defended front. This ultimately led to the surrender of Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox.[2]

The Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9 around noon followed by General St. John Richardson Liddell's troops some six hours later.[2] Mosby's raiders disbanded on April 21, General Joseph E. Johnston and his various armies surrendered on April 26, the Confederate departments of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana surrendered on May 4, and the Confederate District of the Gulf, commanded by Major General Dabney Herndon Maury, surrendered on May 5.[3] Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured on May 10 and the Confederate Departments of Florida and South Georgia, commanded by Confederate Major General Samuel Jones, surrendered the same day.[4] Thompson's Brigade surrendered on May 11, Confederate forces of North Georgia surrendered on May 12, and Kirby Smith surrendered on May 26 (officially signed June 2).[5] The last battle of the American Civil War was the Battle of Palmito Ranch in Texas on May 12 and 13. The last significant Confederate active force to surrender was the Confederate allied Cherokee Brigadier General Stand Watie and his Indian soldiers on June 23. The last Confederate surrender occurred on November 6, 1865, when the Confederate warship CSS Shenandoah surrendered at Liverpool, England.[6] President Andrew Johnson formally declared the end of the war on August 20, 1866. Read more